Émilie Régnier

Émilie Régnier is invested in the quotidian: Where most see business as usual, Régnier finds her greatest sources of inspiration in the everyday—and successfully does so by honing in on hyperlocalized settings (though with her multilayered background in mind, it should comes as no surprise). Canada-born, but raised in Gabon and Dakar, she’s had a storied career, photographing in places like the Middle East, Eastern Europe, the Caribbean, and Paris, where she now resides.

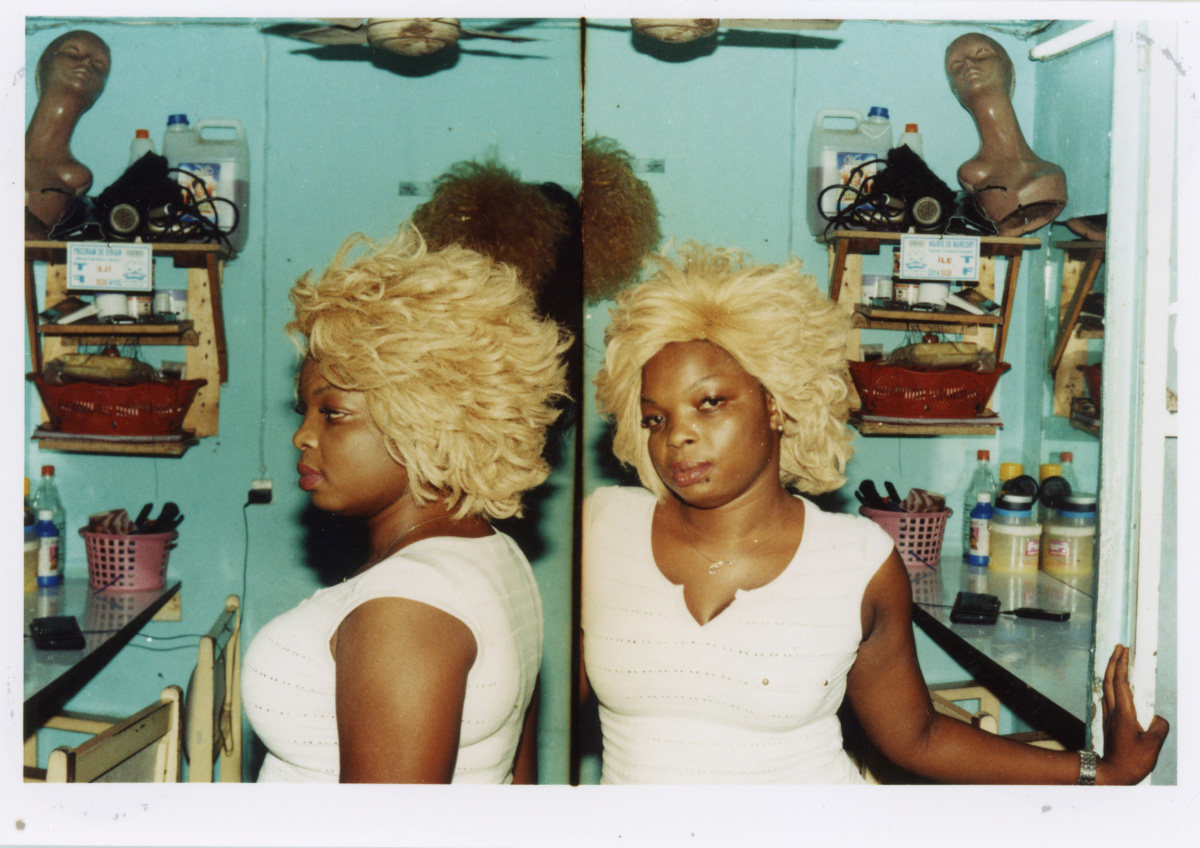

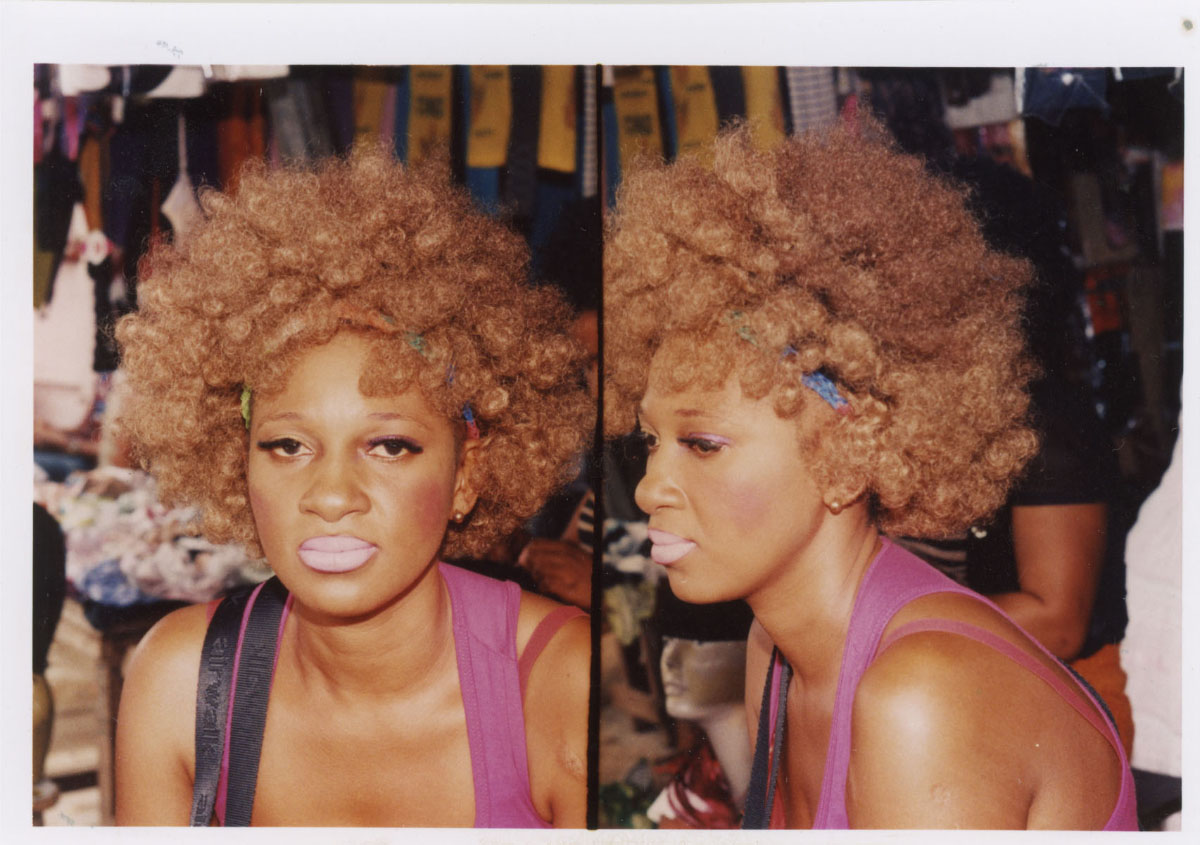

Generally using the techniques of the locals, Régnier upends site- and cultural-specificity to create universally resonant works with a painterly quality. In her “Hair” series for example, she had stumbled across a local hair salon and flipped through a photobook of hairstyles taken by a neighbood photographer. Similarly, in her “Leopard’ series, Régnier was piqued by a local’s choice to wear leopard print, only to find its ubiquity and varied signifying power across different cities. With a highly attuned eye to color compositions and an acute awareness of her settings, Régnier re-frames everyday occurrences where the beholder meets the beholden.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself? Where are you from and how you became involved with photography?

I was born in Montreal to a Canadian mother and Haitian father and spent my childhood in Gabon. I am not so certain about what influenced me to become a photographer, but one thing I am certain of is that as far as I can remember, the camera always held a certain fascination for me. My grandfather bought me a Polaroïd when I was 7 or 8, and then I get my first semi-professional camera when I was 16 and since then, it’s continued on and on. As a teenager, I don’t think I had a clear vision of what I wanted to do with photography. I guess it was mainly the tool I used to build a world in sync with what I was feeling, seeing.

There are so many beauty rituals/products that dictate women's daily routines (think skincare), so what compelled you to do a series on hair?

When I did this series, I had already been living in West Africa for a little while, and the more you get accustomed to a place, the less you see its subtleties. One day I was in a market in Abidjan, and I stopped at some random hairdresser. I started looking through the book of haircut styles they were offering and it was by looking at those photos done by a local photographer named Adama that I realized how powerful a subject of exploration it was. I was mesmerized.

One of the most interesting aspects of the "Hair" series is the doubling that occurs in certain photos, whether it's a mirror image or the juxtaposition of the front and the back. What is the impulse behind that?

I used a technique of local photographers. Unable to afford a digital camera, many Ivorian photographers still work with film; many of them are beauty photographers. Cameras around their necks, they crisscross through the city with the goal of enriching the vast repertoire of the myriad hairstyles available on the market. Once their photos have been developed in the laboratory, they try to sell them for a price ranging between 75 cents to $1 for hairdressers to put in their books. To save a little, they will print two perspectives of the same hairstyle on each print.

You've mentioned how painful and often times expensive these hair procedures can be. Can you explicate that further? (Our male readers need to know!)

The process is painful because it requires you to have your own hair very tightly braided on your head and then the hairdresser will sew the other hair or the wigs onto your braids hair. It’s can be super expensive because some women actually use real hair and it’s a long process.

Your photographs subsume a kind of tension between painterly tableau with photographic "realness, melding the two in a way. Was that intentional? How do you accomplish that formally?

Like I said previously, I myself was very inspired by the local technique. I bought an old camera in a market and expired films that had been under the sun for months and, from there, I pretty much improvised. At first, I was a bit clumsy with cutting and pasting the negative together, so it made for some aesthetic mistakes, but I also wanted the viewer to feel the chaos in the background. I was shooting all the time in overcrowded market where you could buy dry fish, meat, clothes and have your hair done; somehow I guess it was the African version of the American supermarket, and I wanted the photo to show that space. I did not want something with a “pure” aesthetic.

Did you use a specific local technique for that portfolio too?

I shot this series with a medium format Mamiya 7 in analog.

Any memorable stories you'd like to share while shooting? Any difficulties you've encountered?

So many memorable stories, but the one that comes to mind is the moment when I was in the Congo DRC working on my “Leopard” series. I was supposed to photograph this amazing tribal chief who is very important in Kinshasa. I went to his place three times before we actually did the photoshoot—he had to get in touch with his dead ancestors to make sure it was ok for him to be photographed. We started the photoshoot in the cemetery and at some point, he paused and asked me if he could change his clothes, so he came out in this amazing red suit. Once we were done shooting in the cemetery, he asked if I could do one last shot for him. He took me to the parking area, and that’s where I shot the pose with his brand new, red jeep. It was a surreal moment.

How did the idea of photographing leopard come to you? Does it have a personal meaning to you?

This series begins with a fortuitous meeting, when I was in a residency in Paris as part of Canada Council's Fellowship and Research Grants. In search of new models at the exit of the metro Château-Rouge, I met a lady who accepted to meet later for a shoot. For the occasion, the woman donned a boubou with a leopard pattern; she was astonishing in her candid originality. The image of this woman inhabited me for days onwards. As I travelled through Paris, I suddenly became aware of the popularity of the animal print. It was worn everywhere and by everyone, both at Château Rouge, Saint Germain des Prés or in the 16t h arrondissement. This encounter with the leopard made me reflect on photographs taken during the colonial era, portraits of African kings wearing leopard. The universality of this motif appeared as a language to decrypt through my lens, and I started to explore its history and symbolism, which vary according to the country, subjects, and events. It took me two years and I worked in, Texas, Paris, New York, Kinshasa, South Africa, Senegal and Gabon.

In other past interviews, it seems like you're skeptical about the term "artist." Why is there such a hesitation there?

I think it's because when I first started to be a professional photographer, I wanted to be a war reporter and when I actually got to cover war, I realized that I was not built for it. It took me some years to reimagine what my practice would be, to actually get accustomed to the term “artist.” Now I am more comfortable with it as I want explore further, along with other mediums as well.

interview SUNNY LEE

“From Mobutu to Beyoncé”

Bronx Documentary Center

April 15th — June 4th, 2017

Images courtesy of Émilie Régnier

www.emilieregnier.com

More to read