Ben Kreukniet

Ben doesn’t like rigid definitions, and perhaps that’s why his work moves between different worlds: live music, generative art, stage design, and technological research. He collaborates with artists like FKA Twigs and Massive Attack, but also builds more personal, self directed projects like the AWOS, performances with Silvia Jimenez (JASSS), where intuition matters as much as technique, and the process counts more than the result.

He comes from an unconventional background, taught himself the software he uses, and started by distorting the sound of a guitar to make it something else. What drives him is a near-obsessive desire to make the invisible visible: a vibration, a tension, a mistake.

In his work, nothing stays still: the light flickers, the sound breathes, the space changes shape. He’s not interested in spectacle, but in moments that stay with you, even if you don’t immediately understand why. His sense of ethics isn’t theoretical. It shows in the tools he builds, the choices he makes, the care he puts into every system.

In this conversation, he talks about control and release, acid green and silence, trust, failure, long processes, and the small miracles that sometimes happen, live, in real time.

DUST is built on 3D scans and generative logic. To you, what is a digital environment: a space to inhabit, to observe, or to get lost in?

I’d say all three. They’re just different levels or vantage points and we’re constantly adapting our choices to the situation. Sometimes you want to keep your distance and observe from the outside - like a scientist looking into a petri dish. Sometimes you choose to step in and participate, and sometimes you allow yourself to be all in, as if nothing else exists outside of that time and place.

Of course this doesn’t only apply to digital environments. The same holds true for the experience of a painting, computer game or live performance - it’s a question of your curiosity, the work and the conditions. I think it also applies to the process of creating. I like working with generative and real time tools because once you’ve built a system you can switch into a different mode and intuitively find spaces between what was defined or known.

In AWOS you describe the use of computer vision as (mis)used). What does it mean to you to sabotage or distort technology for expressive purposes?

I first became interested in computer vision during university, where the engineering department was trying to teach a car to navigate down rural highways on its own. Computer vision was obviously a big part of that, and to improve the system they needed to visualise what the computer was detecting. Some things the machine had trouble with you hadn’t noticed before.

I became interested in this feedback loop where how machines see can change the way we see. When creating work you have to think about what to show, how it will be seen, and the reality that more people will probably see the work second hand - through their own screens rather than in person.

So there’s this transformation from space to space to space. With AWOS in particular, Silvia and I wanted to embrace the fluidity of this, to create something that is in the process of being created or transformed. Like thinking of painting or sculpture not as objects but as verbs - an active expression that started way before you arrived and will exist long after you leave.

You’ve worked with both radical and mainstream artists. What do you try to preserve as a core visual language, even in highly commercial or institutional contexts?

Whilst I have been very focused on visual language, my interest and focus is increasingly on process and people, and letting the visual language emerge. If anything, visual language is a recursive thing where each project and phase of research influences the next.

I’ve been lucky that early on I got to work with artists who I deeply respect, both for their work and their principles, and I learnt a lot from that. Regardless of context, I think good work comes from respect, intention and a lot of hours. The visual language is partly chosen and partly uncovered. It’s like it’s already there and I'm just digging it up.

The control I have however is in the tools I use, the structure I apply to my work, and a spatial approach I apply to everything, regardless of the final format. That brings a framework that - across all contexts - leaves its mark. Because over time I learnt to use tools in a certain way, and try as I might to escape from those learnings they remain. In the end, with projects being quite varied in context, one thing I have to cling onto is process. It provides a foundation and a reference point. The visual language I'm drawn to is a result of intuitive decision making within a clear structure - a sort of controlled or bounded uncertainty.

Is there a type of light that keeps returning in your projects? Or a visual texture that obsesses you?

Good question. I think I'm still figuring this out. I look for structure and absence. I like noise, strobes and haze because they create abstraction and disorientation. I love how smoke shifts the colour of light to simultaneously create texture at different scales. I quietly love green light because it always feels a bit weird.

I look for either intensity or beauty. If it can be both, great, but it has to land at least one of those things well. An after image can be more important than the image itself.

I do remember using an intense red-green-blue strobe effect during one song with Massive Attack and the guitarist told me he couldn’t see his fingers anymore. I thought why do you need to see your fingers? I calmed it down a bit after that.

When was the last time a technical error opened an unexpected path for you?

Maybe not exactly a technical error, but when working with Sub for Travis Scott we built massive SFX towers that integrated a lot of Pyro and atmospherics. When the fabricator was assembling them on site they realised the tubes feeding the fog machines wouldn’t fit in the structure, so we ran them on the outside and it looked way better that way. I was like yeah that was totally the idea all along.

With software, I often experiment with extreme parameter values that make absolutely no sense. It results in a lot of errors. I discovered a lot this way.

If you could create a performance in zero gravity, in space, where would you begin – light, sound, or disorientation?

Probably intense sub bass and complete darkness. It might be very claustrophobic. Maybe I’d add one slowly orbiting light behind some kind of womb like membrane. I want to do this now.

What do you imagine for the future of live performance – ever more digitally expanded, or a return to raw physicality?

I think the digital elements will become increasingly blurred, embedded, and things will become more raw. But raw can also be refined. It doesn’t equate to un-intentional. It’s just getting closer to an idea by removing parts that get in the way. Digital elements can be raw materials.

Personally I'm interested in the real-time possibilities of digital technologies, to trap some aspect of the here and now and to create systems that are always changing. To inject time, motion and uncertainty into the work.

What has been the most intense moment you’ve experienced during a live performance – as the creator, not the spectator?

Two come to mind immediately.

The first is doing a show with Massive Attack in Sofia, Bulgaria, in an old ice hockey arena. During the song Inertia Creeps we started typing out political newspaper headlines - the audience was stomping their feet so hard it felt like the ceiling was going to come down. It was incredibly powerful.

The second, very different, was the third or fourth show of AWOS, with JASSS, and it’s like all of a sudden I saw what we had created together and I became really emotional and proud. Like I was watching someone else’s show and it really moved me, but it was ours. I couldn’t believe we made it. It was a kind of out of body experience. I try to remember that moment every time I’m doubting myself, which is way too often.

What’s the difference you feel between working for artists like FKA Twigs or Massive Attack and something more intimate like AWOS?

They carry different degrees of connection.

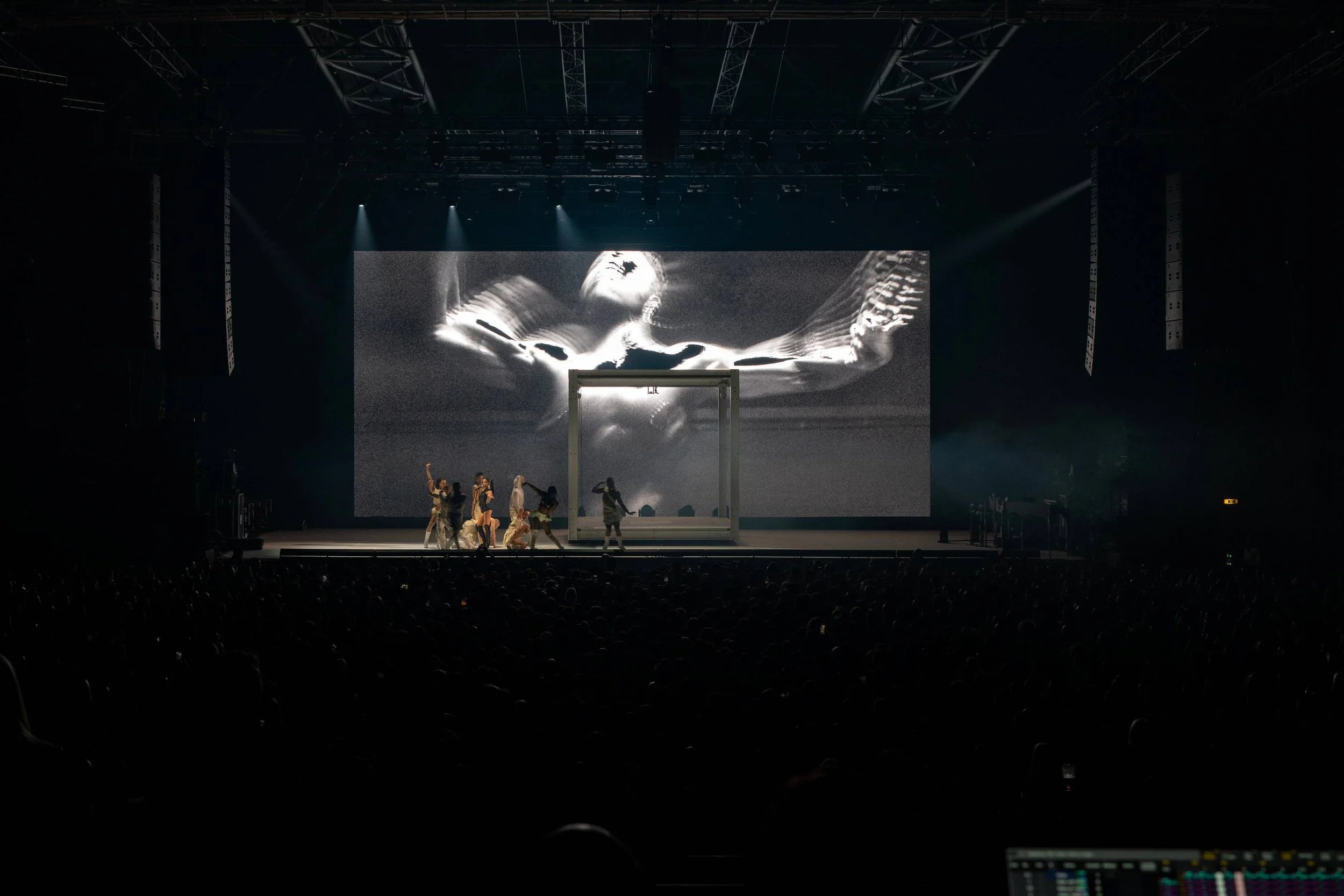

I’m very proud of the FKA Twigs shows. Even though our time together was limited during the preparation process, there was a huge creative energy and the shows turned out beautifully. I worked with Sub, Jordan Hemingway and a long time collaborator and friend Andrea Cuius (Nocte) to create a world for her and the choreography to exist in. The result was incredible.

With Massive Attack there’s years and years spent together building the shows, so it’s more personal. It has been an evolving entity, constantly reflecting the here and now. But it’s also a team effort with many different contributors. I’ve learnt a lot from this show and everyone involved, not least of all how to deal with show production stress. It has been incredibly rewarding and I'll have the music on repeat until the end of my days.

The AWOS live shows are something Silvia (JASSS) and I built together from the ground up. There’s no-one giving direction or making demands. We can do what we want, but we have to do it ourselves. I have to face my own limitations head on.

The process for making the show was kind of not making the show. Over many years we’ve spent countless hours in conversation - not specifically about the show but about whatever was on our minds at that moment. Our schedules have meant that many of these conversations happened late at night or early morning. The themes and aesthetics of the show have precipitated from these conversations - carefully and very intentionally, but without forcing anything into a mold. It has been a real exercise in intuition, where the complexity and layers have formed over a long time.

We never had the resources for full rehearsals, so it has been a case of trusting each other and the process. We don’t experience the show as a whole until the audience arrives and, every time, I walk away in awe of what we’ve created.

Is there a piece of technology – even a simple one – that has forever changed the way you create?

So many of them, but if I have to choose one I’ll select noise cancelling headphones, because sometimes you need to tune out.

What kind of teenager were you? And was there a moment when you realized your language would be light, sound, and moving image?

It has been a bit of a happy accident.

I grew up in Australia. I was a shy redhead with glasses who was interested in math and really not interested in football. I was not the most popular kid in the class. I had a family that taught me I could be what I wanted to be but at school I didn’t quite fit into the boy mold that was expected. I recall being labelled as either ‘gay or European’.

I signed up to drama classes to kick my ass out of my shell and, like many, found my place and people through music. It continues to be the glue for me. When you’re with the right people it’s easier to see that conservative opinions should not be your problem.

After a trip to the Venice Biennale in my 20s I became really excited about creating installations and taught myself whatever software I could get my hands on. I didn’t really know what I was doing so I needed the tools to simulate ideas ‘in the box’ before committing to anything. Also I’ll have to admit that it felt a bit like playing a computer game for an actual purpose, which was fun.

At the same time I was building effect chains to make my guitar not sound like a guitar and discovered modular synthesizers. This process of building instruments and choosing what variables I cared about most led me to how I work with moving image.

You build instruments, you learn to play them and then you can express yourself. 10,000 hours later, you make some things you actually like, some other people like it too, some people pay you to make things for them, and your never ending quest for purpose and validation continues.

What role does ethics play in your use of data, scans, and surveillance-based technologies? Is it something you consciously address or let emerge through form?

I let it emerge. I’m not trying to violate privacy but interested in observing through the lens of emerging technologies. Like Nam June Paik’s genius video sculpture of a buddha statue watching its own image on a tv screen - both observing and being observed by modern technology.

Interview by ARMANDO BRUNO

What to read next