Elsa Rouy

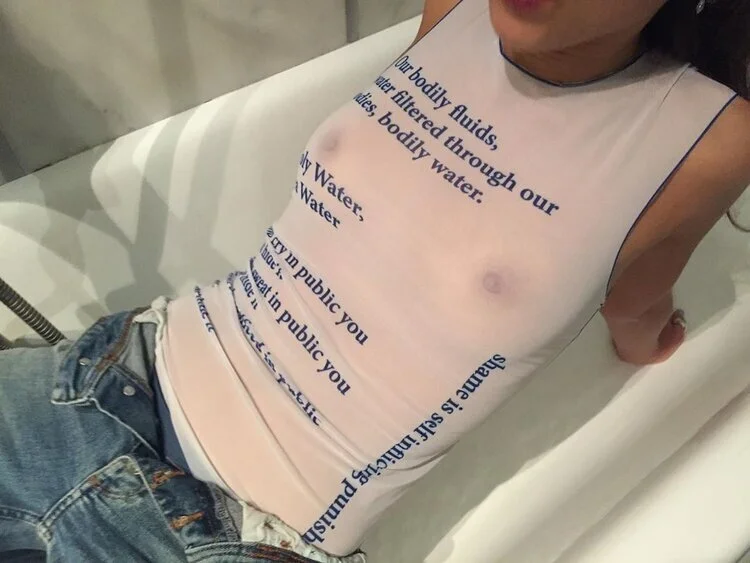

With paintings that are quick to test the anodyne, Elsa Rouy is an artist unafraid to explore the more prurient aspects of our bodily functions and relationships. Currently studying at Camberwell College of Arts in London, her work has a unique penchant for transgression — using erotica and humour as a means to explore how we embody contradictory feelings of shame, pleasure and codependency.

Elsa’s work is fierce and provocative: adroygnous subjects embrace and exchange fluids, groping wildly and gazing at one another in torrential frenzy. It is a monstrous language of venous and opaline flows, a miasma of mutual deformation that splinters any sense of a solid or fixed identity. Fresh off the back of their debut solo show in London, Plastic Doesn’t Sweat, we speak with Elsa about her taste for the voyeuristic, the inevitability of death and why she’s proud for her art to be called “disgusting.”

In October 2020, you had your first solo show with Guts Gallery — in collaboration with Soft Punk — called, Plastic Doesn’t Sweat. Can you tell us about the theme for the exhibition and the works included in the show?

I included four artworks: Falsifying Catharsis, Spout Out and Splash About, Bring a Bucket and a Mop and Tugging on Each other’s Ego Straps alongside three latex garments. I think the paintings in Plastic Doesn’t Sweat were a catalyst for what I’m now exploring in my work. For those paintings, I was focusing on relationships between people — notably dependency, vulnerability and pleasure — using erotic images and humour to investigate this. The exhibition concentrated on the idea of emotionally shielding yourself and the duality between false and real emotions, shown through fake body parts that imitated sexual organs, alongside the implication within the title. I wanted the viewer to be a voyeuristic counterpart to the paintings and question the boundaries of comfort and safety that they feel.

Bodily fluids — especially their exchange and co-contamination — are a central axis in your work. The last year has seen an increased fear — a near phobia of this exchange. How has our changing relationship to the body during the pandemic affected how your work?

To me, bodily fluids are the connection to being human as we all have the potential to produce them. I think they also relate to the idea of mortality, our need to hide them partially stems from them being a reminder that we will inevitably die. For this reason, I find the increased fear quite interesting, especially being someone who is a bit of a hypochondriac — having previously suffered from extreme fear and anxiety of falling ill. Bodily fluids during the pandemic have become the embodiment of potential death, so I think it caused an even stronger taboo around them as they are now seen as contaminants. Saying this, I have found the pandemic fairly cathartic for dealing with this anxiety. Personally, I was already terrified of the idea of a foreign body entering my body. It’s a boundary thing — a disruption of our perfect self, much like an intrusive thought. I think this is evident in my artwork.

Your paintings are filled with androgynous erotica, the gaze and the abject — they are also expressions of a child-like dependency and liberation. There are gushes of milk from the breast, flows of red blood cells modulating the placenta, jets of sperm sucked in by the womb. What informs this set of motifs in your work?

It mainly stems from my interest in internality and exteriors and the crossing and distortion of the two. The spouts of fluid coming out and going in are breakings of a surface. For me, there’s an emotional significance that coincides with the imagery of expulsions and intrusions. Mainly centred around feelings of shame and guilt and the releases or harbouring of these. I used to use erotica to transgress certain emotions in a way that can be visually understood by an audience, however, now it is much more to do with relaying thoughts that I have had or ways that I have viewed myself. I like to keep the figures fairly androgynous so that they are to an extent, genderless and can be representative of anyone regardless of gender. Recently I have started to depart from this. I am consciously painting women that can be seen as monstrous and violent to relay my personal relationship with myself. I try to form an affinity to the parts of myself that are potentially not acceptable in western society. I have also started to use the imagery as a critique and subversion of mainstream representations of women throughout history, without apology.

Your Instagram bio reads, “Disgusting. And bad art.” Where does this quote come from, and what does it mean to you to appropriate and uphold this comment?

The quote comes from a comment left underneath one of my paintings on Instagram. I found it really amusing, everyone is entitled to their own opinion so I wasn’t offended. I think I found the bluntness and the fact that my work had the capability of making someone offended comical. As it was about my work, I decided to appropriate her comment and leave it in my bio as if it was a review, a bit like what you find on movie posters but bad. The woman in question actually did quite exciting paintings of horses, it’s a shame she didn’t have the same attraction to my work.

You are one of Guts Gallery’s first “championed artists” — can you tell us a bit about how this process has been for you, and how this alternative relationship between artist and gallerist looks to set new standards for the art world?

I’ve really enjoyed it so far. Ellie is super easy to work with and always allows me to have the main say if I do/don’t want to do things, she’s really helpful with making sure that I am treated fairly and genuinely wants to see me (and the other artists) succeed with our practice. We review the championing every six months so it’s really nice and free and there’s no pressure of feeling like you’re tied to something if anything ever happens where I no longer feel like it’s right for me. I think it is setting a new standard of transparency between the artist and the gallerist, be this financial or general expectations, creating a more equal relationship between each other where your voice isn’t ignored. Time will tell, but currently, I think it’s a much healthier working relationship as the power is distributed evenly.

You are currently working towards your final year BA Painting at Camberwell College of Arts, how have you found studying at Camberwell, especially during the lockdown, and what have you got planned for the final year?

I enjoyed studying at Camberwell, although the general management of UAL wasn’t the best at adapting. I would say for my course, the tutors tried really hard to get us studio time and make the transition online as easy as possible. It was really annoying not having a constant studio and working mainly from my bedroom, but I think I learnt a lot about overcoming physical and financial limitations which can only positively influence my practice. I’m currently thinking about my degree show, I’m not sure what I’m going to do just yet but I’m going to try and be ambitious, maybe a very large painting or a series of 5-6 works.

Is there anything else coming up for you in the future?

There are a few things in the works for this year, hopefully, all exciting.

interview CHARLIE MILLS

What to read next