Heksehammeren

The witch trials are not just a historical episode — they are a system, a logic, a story we keep retelling with new faces. Premiering at the Queer Film Festival in Oslo on September 23rd, Heksehammeren (The Hammer of Witches) by Norwegian filmmaker and visual artist Marin Håskjold doesn’t resurrect witches as myth or metaphor, but as political subjects trapped in cycles of fear, gender violence and social control. Often blurring the line between natural atmosphere and psychological mental states, the movie, set in a small Scandinavian village, traces the brutal progression of the witch trials of a group of women— not just through interrogations, but through endless torturous rituals used to extract confessions. What remains unspoken in Heksehammeren, why the women are saying what they are saying, all the fragile bonds and gossips between them, somehow resonate more powerfully than the words themselves. By re-enacting the trial scripts in a time of pervasive gender inequalities and contemporary extractivist politics, the film allows their powerful legacy to emerge — a confrontation between past and present, text and subtext, institutional violence and the radical hope for social justice.

Marin Håskjold is a Norwegian filmmaker and visual artist based in Oslo. Håskjold moves between documentary and fiction, often blending documentary realism with performative fiction.

Alice Minervini is an artist and researcher exploring intersections between autofiction, camp aesthetic, fashion folklore and affects theory as ways to envision alternative futures.

What was your encounter with Heksehammeren Malleus Maleficarum —politically, socially, or even personally?

I clearly remember the first time I heard of witch hunts.. I was maybe six years old, and we were celebrating Midsummer in Denmark, where they have the tradition of burning witch dolls on the bonfire. When I asked why they did it, my mother told me that she probably would have been burned if she lived back then. Ever since, I have been thinking about what happened to those women that were prosecuted, to later be sentenced and killed. I have always been curious as to how society could end up executing people like that.

The witch trials are an under-told chapter of Norwegian history that cost the lives of 350 people. In Europe at large, roughly a 100.000 faced charges of witchery, and 40.000, predominantly women were sentenced and executed. This makes the witch hunts one of the most extensive examples of human persecution in Europe. Despite this, we never learned anything about it in school, which in turn reveals the continued male dominant narrative of what we define as «history».

We are now living in an age dominated by the rise of incel culture, conspiracy theories, and political turmoil. Not too different from the early modern era, which lay the grounds for the witch trails. When I was researching for this film, I read several excerpts of the Malleus Maleficarum, and it was quite shocking to see how the text indeed was very similar in its hate towards women, and especially promiscuous ones, really resembled incel threads I’ve seen on reddit. I believe it’s important to be aware of how these ways of looking at women – and in general other groups in society – is dangerous, and it motivated this film. I wanted to tell the story of the witch trials in a way that was informative, but also could open for these historical parallels. I believe there’s a lot to learn here that can also help us understand the time in which we are living.

How the movie came together and what was your process with the actresses/actors, especially given the film’s emotional and historical weight?

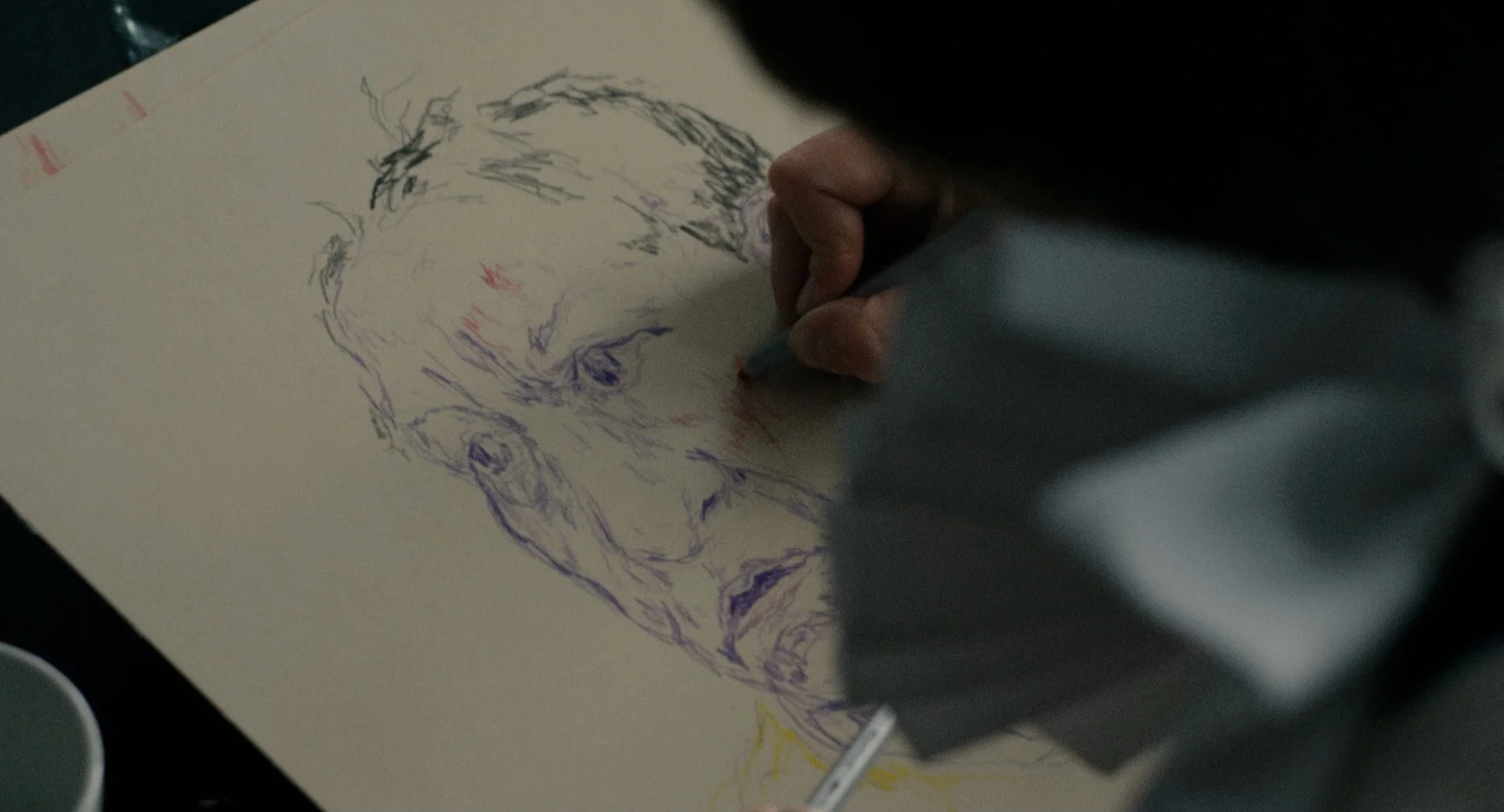

I use the medium of film to try to delve into the mechanisms that make us behave the way we do. In my practice improvisation is key to finding the depth in the story. The collaboration with the actors is one of the most important processes in my productions. In order for the story to appear realistic, we had to find the complexity in all the characters. This is especially challenging when there’s no traditional script, which I tend to avoid in my productions. Rather we improvised together over the actual legal notes from the 17th century witch prosecutions in Norway. The notes are incredibly well preserved. However, we could not escape the fact that they are written by the judging party. Therefore, it is up to me and the actors to try to expand on what went down, and what motivated the different parties to act as they did.

This method makes the shoots somewhat more complex, as we don’t know exactly what’s gonna happen. On the other hand it also generates dialogues and situations that are more authentic which supports my vision of throwing the audience into the situation and giving them the feeling that they are actually present in the room. In this manner the audience become spectators, as if they were seated in the court room, and thus they are invited to reflect on how they themselves would react – imagine if I was being charged with witchery? Or someone I knew?

Did your personal relationship to the subject evolve during production?

Already in the early phase of research, it became clear to me that the witches were scapegoats, in the sense that they were a constructed political enemy that enabled the authorities to gain a stronger grip on the political and societal narrative, and in turn their populations. The story of the witch hunts thus becomes something not merely historical, but equally contemporary. One more recent example is how the Nazis framed Jewish communities, homosexuals, and disabled people as enemies of the Reich. Today we see the same in how the Israeli state is legitimizing its genocide in Palestine by calling the Palestinans «terrorists», and how the Trump regime is targetting immigrants by calling the «illegal aliens». This dehumanizing language is not only violent, it is also extremely efficient in the creation of a common enemy, getting people to follow you.

Your last movie stages a discussion in a women's locker room when someone asks a transgender woman to leave. How does Heksehammeren deepen or shift that inquiry? How do you see these films in dialogue with each other and with your broader practice?

Heksehammeren and What is a woman? (Hva er en kvinne? ) are both rooted in my general interest for the outcasts of society, and how it puts you on the spot.

Community is a strange thing because it is inclusive and exclusive at the same time. It requires a group of people being on the inside, which in turn means there will also be an outside.. Humans are social and co-dependent beings, this makes being on the outside dangerous. The fear of becoming the excluded one is very real, and it can lead us to commit terrible acts.

Methodically, the films also share a lot. The dialogue in What is a woman? (Hva er en kvinne?) was also improvised without a script, based on comment threads from social media. Here, I had been collecting discussions from various feminist forums on trans people. Like the witches of the past, today trans people are being accused of all kinds of things from the brainwashing of children, the killing of Charlie Kirk to high rental prices.

Do you see parallels between the logic of witch trials and contemporary modes of social surveillance or punishment?

In the 15th century the printing press revolutionized how information spread, this coincided with Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum, which in the early years of the printing press was the second most read book in Europe, after Luther’s translated bible. Most historians agree that the witch trials would never have been as extensive, without this new means of technology for spreading information. It was a whole industry of printed manuals that taught readers how to find and eradicate witches. Suddenly people in Norway could read about a witch being burned in Scotland. Today we are moving through a similar change in the spread of information that in turn also is changing our perception of the world. This has led to the manifestos by far-right terrorist Anders Bering Breivik, q-anon or far-right influencers gaining a following that is spreading racism, transphobia and misogyny, across the line. This is further enhanced by politicians, that like the kings and lords of 16th and 17th century Europe are clinging on to power, and doing so by setting various parts of the population in conflict with one-another. The witch hunts provide a reminder that delusions and misinformation are recurring features of human society, especially in times of technological change and social upheaval.

The scenes underwater unfolds as a poetic juxtaposition of the isolation and violence inflicted on women, often put against each other, publicly burned and tortured to death. How important was the setting in shaping your storytelling and what was idiosyncratic in your perspective about the Scandinavian context?

When I started working on this film, this was the first image I knew I had to make. The water test (judicium aquae frigidae) was carried out all over Europe, but particularly in Norway, as a test to see if the accused woman was actually a witch. If she floated back to the surface after being thrown into the water with her hands and arms tied, she was guilty. For many the witches are predominately associated with the bonfire, but personally I have always been more drawn to the water test l because it emphasizes their innocence and also how they in reality were presentenced. As our bodies are filled with air, we would all float eventually.

Heksehammeren (The Hammer of Witches)

Director: Marin Håskjold

Producer: Una Mathiesen Gjerde, Amfitrite Production

Photography Julie Hrncirova / Studio Abrakadabra

Film stills: Even Grimsgaard

Interview by ALICE MINERVINI

What to read next