Rafal Zajko

Rafal Zajko breathes life into his work through performative gestures and a conscious interpretation of historical facts. As elaborate prosthetics, Rafal’s sculptures act like extensions of himself while bearing a close relationship to his body and his past. Catholic traditions and religious motifs meld with the the socio-cultural aftermath of communism, as well as its promises, to activate the corpus of symbolic references that informs a vivid imaginary. The artist’s work introduces elements of folklore, natural cycles and spirituality – which were central to his Polish upbringing – and bridges them with the mechanical side of factory work. His is a practice that produces complex readings of ancient customs and, by weaving disparate narratives into new realities, foresees a future that defies the laws of time.

Your recent show Resuscitation at Castor seems to stage an encounter between technology and folklore, science and myth, natural cycles and artifice – spheres that are conventionally treated as opposites. But the process of resuscitation itself is an act that literally breathes life into a human being through physical contact, and so is very corporal. There are several instances where technological apparatuses and organic forms come into contact and overlap within your work. How have you built your perspective on these aspects?

Prior to the show I had been working on the idea of sculptures that could become active through breath or smoke; I was fascinated by the idea of bringing the sculptures to life, so the title "Resucitation" seemed like a perfect fit. I had no idea when I began making the work some 18 months ago of the obvious associations of the word now, in the midst of a pandemic, or of the works breathing and expelling smoke. Seeing the work now it is eerily prophetic.

These sculptures could be looked at as extensions of myself, strange prosthetics that perform. My body is embedded in every aspect of the work - they are made physically by me, and then animated by my breathing the vape smoke through them, in a performance.

The idea of breathing life into something is deeply rooted in my past, coming from a catholic household in Poland. Bialystok (the city I grew up in) belongs to a particular region of Poland (Podlachia) that includes the largest remaining parts of an immense primeval forest that once stretched across the European plain. A connection to the local folklore, superstitions and mythological beliefs were deeply ingrained in me. I was raised in a working class household with family either working in the factories or on the field. I was deeply obsessed with the machines that aid the workers in both of these settings, and was always interested how they operate - which button does what, what would be the result of pulling certain levers etc.

So to summarise the title "Resuscitation" connects to a range of things. From life-saving equipment in intensive care, to cyclicality of field work and nature: the winter decay to seeding, bloom and harvest.

Narratives from the past are featured significantly throughout your work. They sometimes appear as nods to science fiction, or as references to folklore and ancient books, all of which are often merging or concurrent in your sculptures. How have they informed your practice? Do you see an affinity connecting the ways different types of storytelling can shape our collective imaginaries and feelings of nostalgia?

I would say these are quite complex questions but a core belief of mine is that we better understand the present and future by looking at the past. As an artist I get to create my own realities and weave together many different aspects of my research and interests.

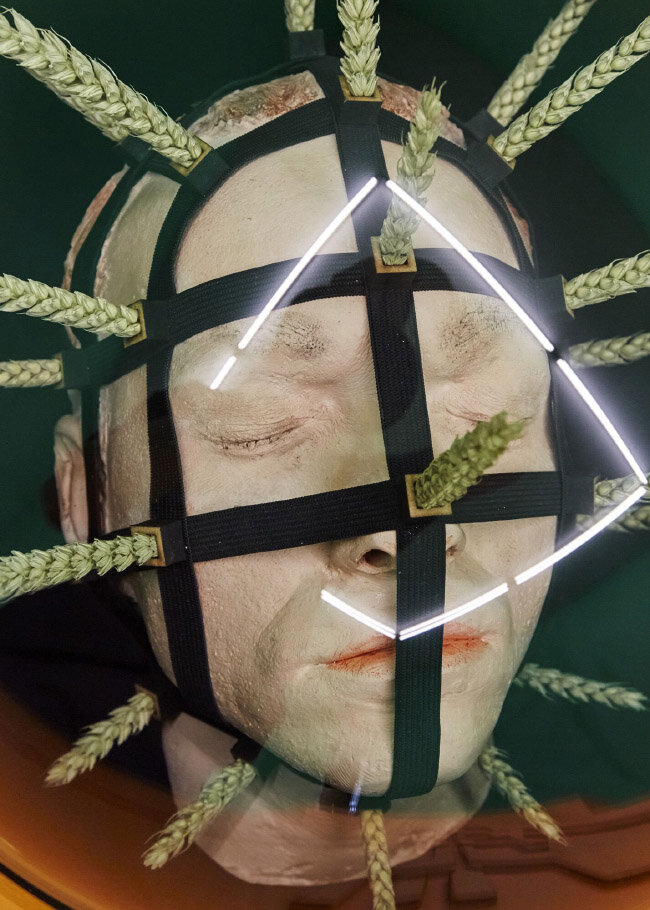

For "Resuscitation" at Castor Projects I looked at the character ‘Chochol’ (pronounced ‘Hohou’) from Polish folklore. He is the personification of a straw structure positioned around rosebushes to protect them from harsh winter conditions. Chochol features in Stanisław Wyspiański’s 1901 novel The Wedding, portrayed as a mischievous character causing havoc when ignored by the wedding guests. You could look at Chochol as both a symbol of necrosis; dying skin and the decay from the winter, and as one of resuscitation; a harvest of vegetation as a means to give us life and the strength to function and grow. Whilst resuscitation and resurrection have crossovers, one is a medical term, the other more mythical. Wheat and barley come to symbolise the rebirth and resurrection, with bread representing the body of Christ during communion. Within the gallery space sits a large sarcophagus which hosts the Chochol character within, keeping him alive, a familiar science fiction image, where the protagonist is protected during their journey to a new planet. Elsewhere in the space we see a wall-based sculpture outlined in the shape of the moth ‘Parastichtis suspecta’, last seen in the UK in 1962, and thought to be extinct until they were rediscovered in 2018.

I was wondering if you could speak about how your Technological Reliquaries came to be. By definition, a reliquary is a container used to store and preserve something holy. To me the title of these works suggests a proximity of the past and future of technology, perhaps a collapse of the two.

The reliquaries pay homage to a hero of mine - Paul Thek. Thek's Technological Reliquaries (1964-1967) (originally titled Meat Pieces), consider isolation from another perspective. In the series we see plaster and wax casts of Thek's limbs and face alongside weird meaty slabs of unknown origins that sit enclosed in glass or plexiglass vitrines. Similar to Francis Bacon’s Head VI, there are visible disfigurations on the subject, and both are enclosed from the outside world. They feel contagious, as if the air entrapped inside would be poisonous and unpleasant for our sense of smell. Technological Reliquaries are a direct reference to the relics and traditions in religious material culture, following the Catholic tradition where casts and replicas of affected body parts are offered to deities or higher spirits with prayers of hope or gratitude for the healing. The glass structures of Technological Reliquaries keep the viewer outside and imprisons the wax-flesh inside, keeping them enclosed in stasis, just as the body of Vladimir Lenin lies in the St. Basils Cathedral at the Kremlin in Moscow. Although controversial, Russia still defends its existence through public funding, with the corpse preserved in baths by various reagents and solutions to keep it looking as if Lenin and his regime could be awakened again one day.

Paul Thek's Technological Reliquaries reached their climatic point in 1967 with the piece Tomb. It was made in the period when Thek moved to Europe and stopped producing objects for the art market. His focus went onto creation of richly detailed immersive environments, mostly large scale and removed from current conceptual discourse. The piece consisted of a large 2,5 metre high structure resembling Mesopotamian Ziggurat. It was painted in pale pink colour and inside of it lay a full size meticulously crafted version of Paul Thek. The figure was dressed in denim with a blackened tongue sticking out of its mouth.

There seems to be a deep link between your sculptures and architectural styles and designs that were led by a fascination with the idea of modernity and tended towards the future, such as soviet architecture, brutalism, and industrial aesthetics. What’s your relationship with architecture?

Being Polish means that I have an obvious connection to this architecture because it was so visible and present to me growing up. I am drawn to the optimism of this architecture and sculpture - the dream of the future as a happy place. As much as there are dark aspects to how communism existed or how it was applied in eastern Europe, its premise was fantastic at its core. Togetherness and building a bright future for humanity were noble incentives, sadly mostly were used only in propaganda. They ignored and used the people at its centre – the workers. I’m drawn to the sacrality of architecture.

Through the use of jesmonite, concrete, steel, bricks, construction materials and embroidery, you seem to place particular attention on the structure and nature of matter. Software, technology and acceleration aesthetics are brought back to a handcrafted, raw dimension that allows the making of your work to emerge. Can you speak about the role of labour in your work?

I love to learn new skills, use unknown materials and master unfamiliar techniques. It’s a way of working that keeps my mind active and suits me. For me working with the hands keeps the mind active and allows time to think. I also like routines - working an 8-9 hour working day, and the feeling of physical exhaustion at the end of it I would describe as total bliss.

courtesy RAFAL ZAJKO

interview VERONICA GISONDI

What to read next