Harmony Korine: The VHS Memory

What if someone had handed Kurt Cobain a camera? If you ever wondered what that rash, uncouth, and angsty world of Cobain’s would have looked like, you need search no further than the early works of Harmony Korine – former enfant terrible of avant-garde cinema (and current god-knows-what), best known for his glossy, star-studded 2014 affair Spring Breakers.

Critically lambasted and blessed with that touch of scandal, pre-Spring Breakers Korine (who was discovered by the legendary Larry Clark while skating in Washington Square Park) and his camera were beacons of grunge-y cinema, depicting the young, bored, and forgotten. Early films like Gummo (1997), Trash-Humpers (2009), and Julien Donkey-Boy (1999) document an almost post-apocalyptic ennui, the restless and bitter poverty of the American Heartland.

Gummo depicts the furniture-throwing, glue-sniffing youth of tornado-struck Xenia, Ohio. (Trash Humpers, and I’d like to stress this, is gloriously self-explanatory) Julien Donkey-Boy follows a schizophrenic man and his broken family.

In depicting lives in post-industrial wastelands that are – devoid of jobs and opportunity – economically and socially petrified, the films remember those who’ve been left behind by time and progress, and tell the stories of those already forgotten, thrown prematurely into the past. The American Heartland is a living fossil, and Korine’s camera sets about capturing it in all its simultaneous pastoral beauty and bored violence. But despite the cheesiness of these phrases, there is a complete lack of romanticization and nostalgia in Korine’s memorials to the children of Middle America – they’re a handsy and almost unlikeable (and the tutting critics will attest to this) picture remembering the idle rage of the forgotten.

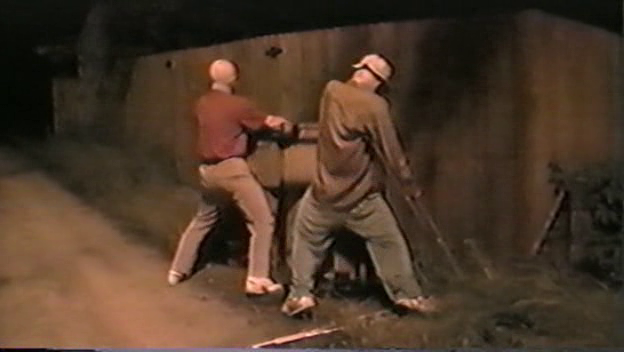

Countless cuts of ragged children whipping dead cats (Gummo), boys in wrestling singlets tackling trash cans (Julien Donkey-Boy), and people humping overflowing dumpsters (unsurprisingly, that’s Trash Humpers) decorate the director’s early film reel. Sad, saintly, and disturbingly hateable, Korine’s character’s come together in their flawed and bored humanity.

The rose-tinted glasses are off, even aesthetically. Doused in copious amounts of grain (a heroic commitment to 35mm film on Korine’s part), and set in a desaturated color palette - not a rosy tint in sight, the films’ home-video-esque cinematography definitely falls in the VHS side of the spectrum. It’s so very unlike the golden retro wash of nostalgic romanticization. It’s always cloudy in Harmony Korine’s world, even if the sun is shining very bright – no room for golden-hour nostalgia here.

And today, in our nostalgia ravaged world, we’re seeing the rise of a neo-Harmony Korine aesthetic: a kind of re-rise of the post-industrial chic, and the particularly Korine-esque drive to tell the stories of those who’ve been forgotten by time.

Andrea Johnson’s trance-y 2016 independent drama has its share of Harmony Korine vibes with a plotline that follows the silent youth of America. Familiarly ragged adultish children who’ve left their abusive homes and/or trailer-park origins to roam free, selling magazine subscriptions for a living, in the open plains of – you guessed it – the Heartland.

Gosha Rubchinsky’s AW 17 fashion documentary that showcases stoic Russian youth trampling the plains of their own heartland, kicking in walls, and narrating their stories in voiceovers reminiscent of the one in Gummo. “Everything is awfully long and transient at the same time,” one model memorably intones in the 9-and-a-half-minute documentary, voicing that crude idleness so present in the fragmentary works of Harmony Korine. Far from romanticizing the pastoral but rough life of his models, Gosha further represents that idea of boredom, anger, and quiet beauty that Korine first explored in the likes of Gummo, Trash Humpers and Julien Donkey-Boy.

And if the content of Korine’s work is slowly regaining popularity, the aesthetic is everywhere. We’re bang in the middle of a VHS aesthetic renaissance, championed by everyone from Disney Parks’ VHS-tape themed merchandise to The XX’s grainy, technicolor aesthetic. And this, I think, is a reason to celebrate. The reappearance of Harmony Korine’s decidedly unromantic style of remembering the forgotten, an aesthetic of memory, which lacks that golden light of nostalgia (ahem Woody Allen), signifies that we’re starting to look at our pasts without romanticizing it, starting to take off the rose-tinted glasses of nostalgia. It’s gotta be. I mean, the alternative (that we all get stuck in a nostalgia-fueled feedback loop with chokers and mom jeans forever and ever) is far too bleak.

More to read