Yannick Cormier

On the subject of cultures and their evolutions, each place has its story, and each story holds an expression of individual timelines through which we accommodate ourselves with the possibility to travel to these worlds. But out of many worlds that exist only a few get to discover and capture the magic that governs many of the foundations of our beliefs today. The lives that we know as humans always have held the grain of mythologies that often cease to get acknowledged as civilizations progress toward a modern lifestyle. Yannick Cormier’s photography captures the nuances of such places where life begins to transcend the generic idea of synchronization. His interests in ritualistic practices and spiritual gatherings along with underground communities make us question and enlighten about the intelligence of inner knowing.

Yannick my first question is on wanting to settle my curiosity on your life prior to 1999, how was growing up in Paris like? How was your social and cultural environment? How did you choose photography as your profession? Please take us through your memory lanes of those early years...

I come from the cosmopolitan and poor neighborhood of Belleville in Paris. At the end of the 1980s, the neighborhood was threatened with being razed to the ground and drugs were everywhere. There were many evictions, walling up, uprooting, suicides, and demolitions. But there is also resistance, conviviality, and parties. It is important to know that since the beginning of the 20th century, several waves of immigrants have come to mix with the workers and craftsmen who used to live here. This colorful mix has given a unique face to this corner of Paris. This is where I grew up, in multiculturalism. I think my interest in other cultures comes from that. I never thought of photography as a profession, but rather as a way of life. Photography came to me late, after the hazards of living in a poor neighborhood with all that entails. As mystical as it may sound, it was a dream that started it all. I simply followed the voice of that dream. So I went to work and bought my first camera.

While working in Studio Astre and assisting great photographers of all time in Paris which was all about glamour and high-profile glaze to moving to India after 20 years, leaving all the shiny ambiance, What was the subconscious calling in those years? What was the voice that made you move? What triggered this shift in the subject of artistic choice?

I just do not like the world of fashion, glamour, and prestige. It was only the images that were important to me. You see, working at Studio Astre as an assistant with great photographers in Paris was a way for me to learn and to train technically with the medium. But despite everything, it was a joy to see people like Klein or Roversi at work. And of course, the aesthetics of fashion has had an impact on me and my photography.

When I worked for the studio, I photographed the ruined walls, the half-destroyed buildings, and the people of Belleville. Today I don't even know where my negatives from this whole series are. After my years at the studio, I was hired as a reporter for a Paris-based news agency. Then the opportunity arose as a correspondent to follow my wife to India who had obtained a scholarship to strengthen her learning of Indian dance.

In terms of cultures and their deep-rooted complexities and influences, how would you describe your emotional and psychological traveling in this physical transition that you adopted? Were you prepared with an aim and goal when you moved? Can you describe a few of the behind-the-scenes moments while documenting in India? Some moments that you wish you could’ve capture but couldn't?

When I came to India in 2003, I had no other purpose than to make photographs for my agency. So I covered the 2004 elections, the World Social Forum in Mumbai, and so on. At first, I was supposed to stay for one year only. After that first year, my wife and I decided to stay on.

To answer your question about the emotional and psychological, it happened and in an unconscious way an absorption of what stranger to me was to arrive at the point where my individuality, with my culture and my own identity, opposes resistance to the total assimilation. It was at this point that I could feel the fundamental difference with the object of my action and could best appreciate this new culture.

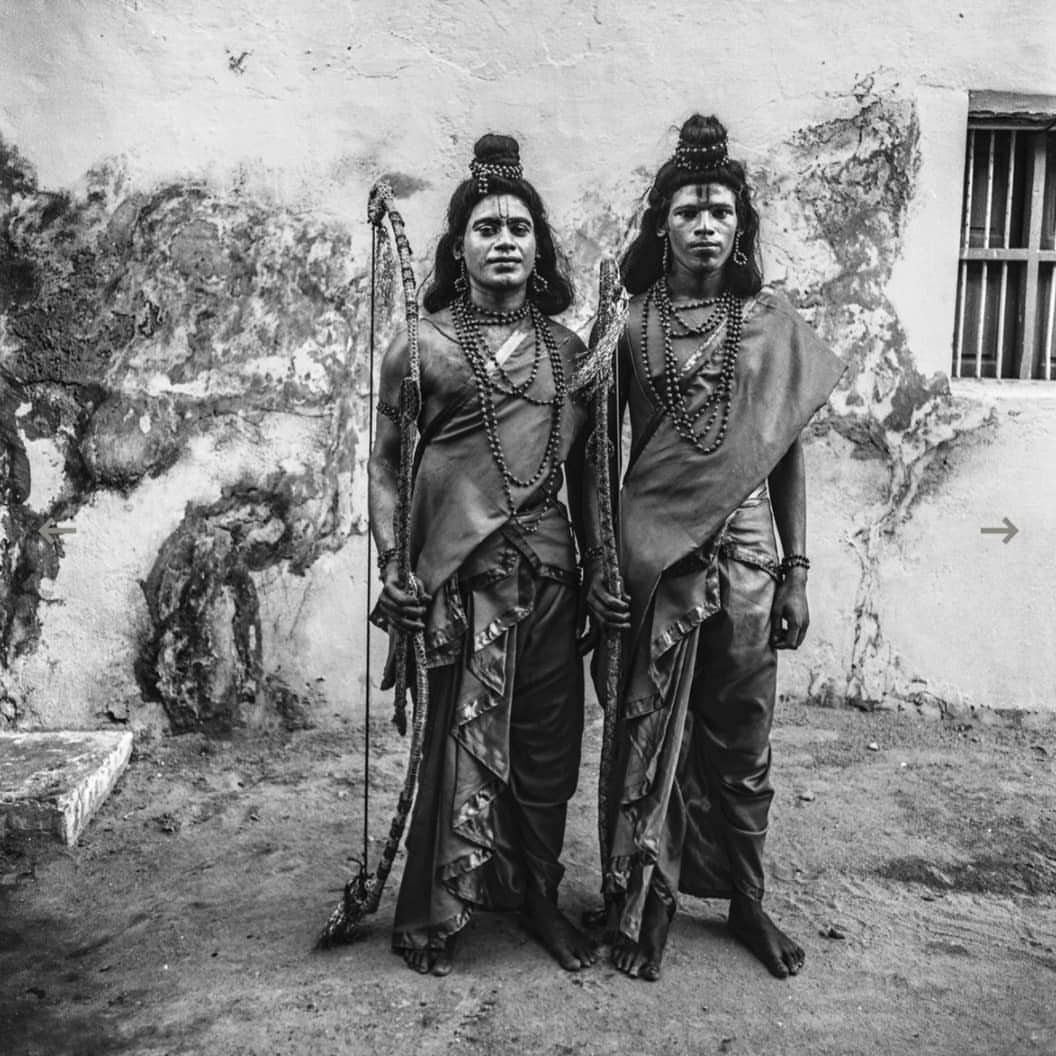

In other words, in the first step, I freed myself from all prejudices, and in the second step, I immersed myself in the local culture, to arrive at the moment when the two cultures (mine and the one I encountered) collided. This implied that my being, could not be completely assimilated into the other. I felt the limits of the cultural gap where total fusion was impossible. I concluded that one can only assimilate or mix cultures up to a certain point, there will always be a core of each culture that will remain, hence the need to recognize, and appreciate, the diversity of cultures. I can tell you about a scene; One day I went back to see the Masi Magam festival in Mahabalipuram, which is celebrated by Tamil Hindus. On Masi Magam day, idols from the temples are taken in procession to the shore of the sea for a ceremonial bath. The devotees who crowd around the procession bathe in the water to get rid of their sins. I arrive at the site at six in the morning. By the sea, celebrations are already well underway. The atmosphere is electric, there are many people and the air is full of mysticism. The men and women are in a trance, the light is magnificent! I came with three films, that is 36 possible photos with my medium format camera. I don't know why but I couldn't connect, I feel that the pictures are wrong. When I have only one possible view left, so I decide to stop and soak it all in. After a while, I look at a young woman who is swaying harder and harder, she is in a trance. I myself am in a state of exaltation. It was like a vision and at one point I press the shutter for the last picture. I like this image very much, the movement of the hair draws a circle like a mandala, and there is the plasticity of the symbol. You see, these moments are gifts of reality, and it is already great to live them. I don't remember the moments I wish I could have captured but rather the rituals I haven't done yet like the Gajan festival in Bengal and the annual festival of the Kodungalloor Bhagavathy temple in Kerala.

Sir the subjects that you have covered in the Indian landscape are shocking, uncomfortable, esoteric, and dramatic at first glaze, Id like to know from you what is it about humans as species in Indian society and communities that needed your attention? What brought you to consider living in and focusing on such places?

I don't think my photographs are shocking, but I agree with the word uncomfortable. From my early days in India, and more particularly in Tamil Nadu, I entered the Tamil world, which fascinated me to the point that I felt the need to know it. For fifteen years, I photographed the festivals, and the rituals and insisted on the wonder of my encounter with the mythological universe of the Tamil people. Because it allowed me to reach the world that is hidden behind things or inside oneself. It was in 2010 and almost at the same time that I became interested in the Aravanis or Hijras (transgender) community and the Narikuravars (South Indian Gypsies). Two groups that are forgotten by the "Indian economic miracle" and chose to continue their rituals and traditions. They are parallel civilizations considered inferior by the other castes. For my In-Between series on the transgender community, it all started with my encounter with Malaika at the annual Koovagam festival in Villupuram district, where many transgenders from all over the country flock to this village to marry Lord Koothandavar, re-enacting a scene from the Mahabharata about Aravan son of Arjuna. Malaika has always considered herself a woman. In the mid-2000s, after many surgeries and hormone treatments, her body finally matched her identity. In the city of Chennai, in southern India, Malaika is more than a respected member of the community, she acts as a mentor and matriarch.

It was through our friendship that I was able to get into the community and photograph it for seven years. I did this work because I was fascinated by their energies and their dignity, despite the fact that they are ostracised. Although it seemed to be an ethical or political issue, for me it was much more than that, it was personal. I saw their struggle, their suffering, and their incredible self-sacrifice.

Your photographs cover ritualistic events, social fantasies, distorted identities, dreamy fiction, etc... What lures in these subjects in particular and how do you personally view such topics?

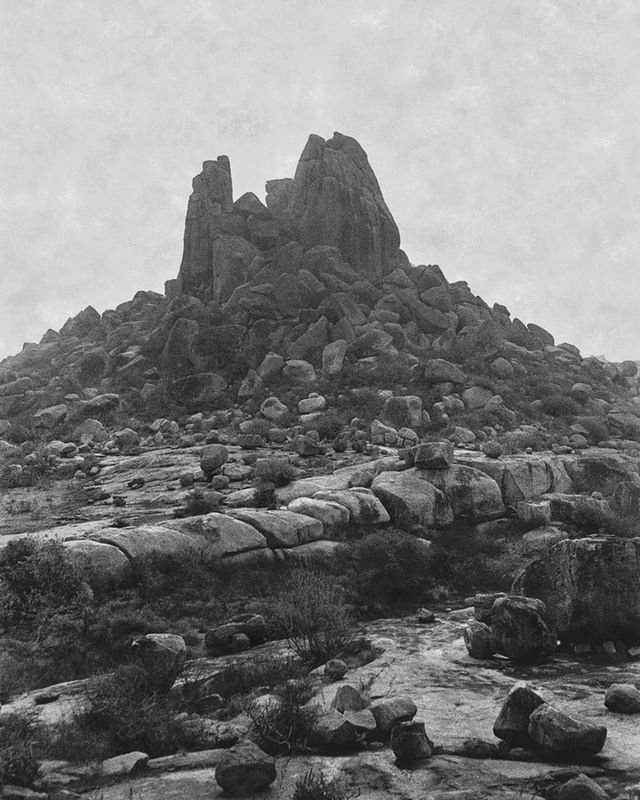

What interests me is that part of humanity that has kept deep physical and psychic links with nature and the rest of the living world. There is also an effort to engrave on hard stone certain images or symbols to incise, one would say, reality, up to the point where, as if by transparency, one obtains something other than what is commonly called reality. There is also the notion of hidden and complex identities and projected appearances. For me, ritual is one of the things that saves humanity. It is a way of forgetting the hard life. Even if sometimes the suffering is palpable, ritual helps people to live their lives with dignity. I like people whose way of life is to mythologize everyday life. It is therefore a matter of the question of interpretation and the meeting points between nature and culture. This liaison can also be found in my series Tierra Magica about the rites of mask in the Iberian Peninsula. Finally, photography is probably a ritual for me.

You have been to various places in the world, can you tell me the places which moved you intensely?

Of course in India, there is a vibratory weft, animated with energy and vibration well-felt in this land. As Shiva's damaru(Drum) symbolizes the primordial sound from which the world is created. Shiva uses it and makes it beat in rhythm with his dance so that the universe is ready to take shape again. There is also and by its gigantism the Himalayas which impose humility. The aestheticism of Javanese culture and the sensuality of the telluric forces of the island of Java moved me.

How do you commence photographing in such open places? How do you make people comfortable with you, and how do you work within the energies of the surroundings?

I want to make it clear that for me, the surroundings and people are part of the same energy. And that I cannot work in the indigenous world or in certain communities if there is no complicity and respect. So if I am in a certain place at a certain time, it is because I know in advance that the symbol activated by the ritual interests me and speaks to me. People usually feel this from you and trust is quickly established.

What is the message that you have for people? What do you wish people to be more sincere and considerate about?

I don't have a message. But Faced with the conquests and domination of Nature and the wild, which have imposed a utilitarian and mechanical vision of the world, I consider it to be time for us to explore another relationship with the world.

Please tell us a bit about your next projects and places that you are looking forward to covering.

Pagan Poem is my ongoing project that follows my two previous books published in 2021, Tierra Magica (Light Motiv Editions) and Dravidian Catharsis (Le Mulet Editions). This project is still interested in the meeting points between nature and culture, symbolic identities, mythology, religious ceremonies, animism, megalithic sites, funerary rites, the shamanic universe, and other exorcisms through a series of photographic essays on ancient practices that have survived by reinventing themselves on four continents (Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America). It will take me a long time to set up and find the funding.

interview JAGRATI MAHAVER

More to read