GraySkiesForever

Alexey Seliverstov, known under the moniker GraySkiesForever, doesn’t compose songs, he renders atmospheres. His sound doesn’t announce itself; it hovers, flickers, remembers. From tattooed skin to generating code, GraySkiesForever is not just a project. It’s a process of erasure, memory, and resistance, woven into sonic weather.

Exiled from his homeland after rejecting its war, Seliverstov’s music carries the residue of loss, of home, of belonging, of silence that cannot be spoken. In his soundscapes, the organic and synthetic breathe the same air. He doesn’t ask us to follow melody, he invites us to inhabit mood. Alexey doesn’t seek to be understood; he asks us to listen differently.

To begin with, the name, GraySkiesForever. It instantly resonates with your music. I wonder how your life was growing up, and what your academic background has been.

Honestly, I love this name, because its meaning has changed over the years and attached itself to different stages of my life. The funny thing is, it started with a tattoo. Sean from Texas did it for me.

About ten years ago, I got this huge tattoo on my right arm, and he simply titled it GraySkiesForever. A year later, when I created my Instagram, I used that name. Unexpectedly, that account changed my life. My success started from that project.

The name feels even more symbolic now that I live in Los Angeles, where the skies are usually blue. It connects me to where I came from, Moscow, where I grew up in the 1990s. That time was extremely hard; Russia had the highest homicide rate in the world. There was this constant presence of danger and anxiety, and Grey Skies came from there.

And now, GraySkiesForever feels even heavier. That part of my life was abruptly cut off. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, I’ve spoken out publicly, supported protests, made donations, and now I can’t return. If I go back, I’ll face years of imprisonment. It’s a deep sadness I carry every day. In a way, the name has become a symbol of what I lost, and what I still carry with me.

I don’t have an academic background. I studied law for a couple of years and then worked as a programmer, making web games and interactive tools. That experience turned out to be really important. Now, I build software for music, and this blend of sound and technology has become the foundation of everything I do.

How did music happen to you? Please take us into your life before all this began, and how it began.

I don’t remember life without music. It was always there. I was obsessed with synthesisers from a very young age. But one moment stands out, when I was seven, I ended up in a children’s hospital. I was there alone for a week. One day, walking near the hospital with my mom, we came across these street sellers, kind of like a black market. They were selling a little toy synth. It had only a few preset sounds, nothing serious. But for me, it was one of the happiest days of my life.

From that moment, I started improvising and playing. I even recorded some of it. I was the happiest kid in the world. That tiny synth sparked something huge in me.

I remember watching TV and seeing people play big Yamaha or Roland keyboards. It felt magical. I used to have this recurring dream that I had one of those big machines, and when I’d wake up, I’d feel disappointed. Back then, there was no internet, no way to learn more. But I was already fascinated by the idea that I could create sound from scratch.

Nature and industrial spaces hold an important role in your craft. The sounds in nature, in juxtaposition to various atmospheres in analogue and digital tools, make a contemporary setting for what you produce. What do you think of technology, cityscapes, and our natural habitat?

I’m inspired by cityscapes, because the city I live in, Los Angeles, is full of amazing collage-like elements, from wild animals to freeways and birds. That all makes it unique. And I can't say I use city sounds in my work, because I tend to be closer to nature. I mostly use field recordings of natural places, along with synthesisers that emulate the behaviour of nature.

I build a world where everything has that level of asynchronicity, where sounds feel spontaneous, like something not produced by a human. I program each element to behave more like it belongs in nature, and that’s something I’m obsessed with.

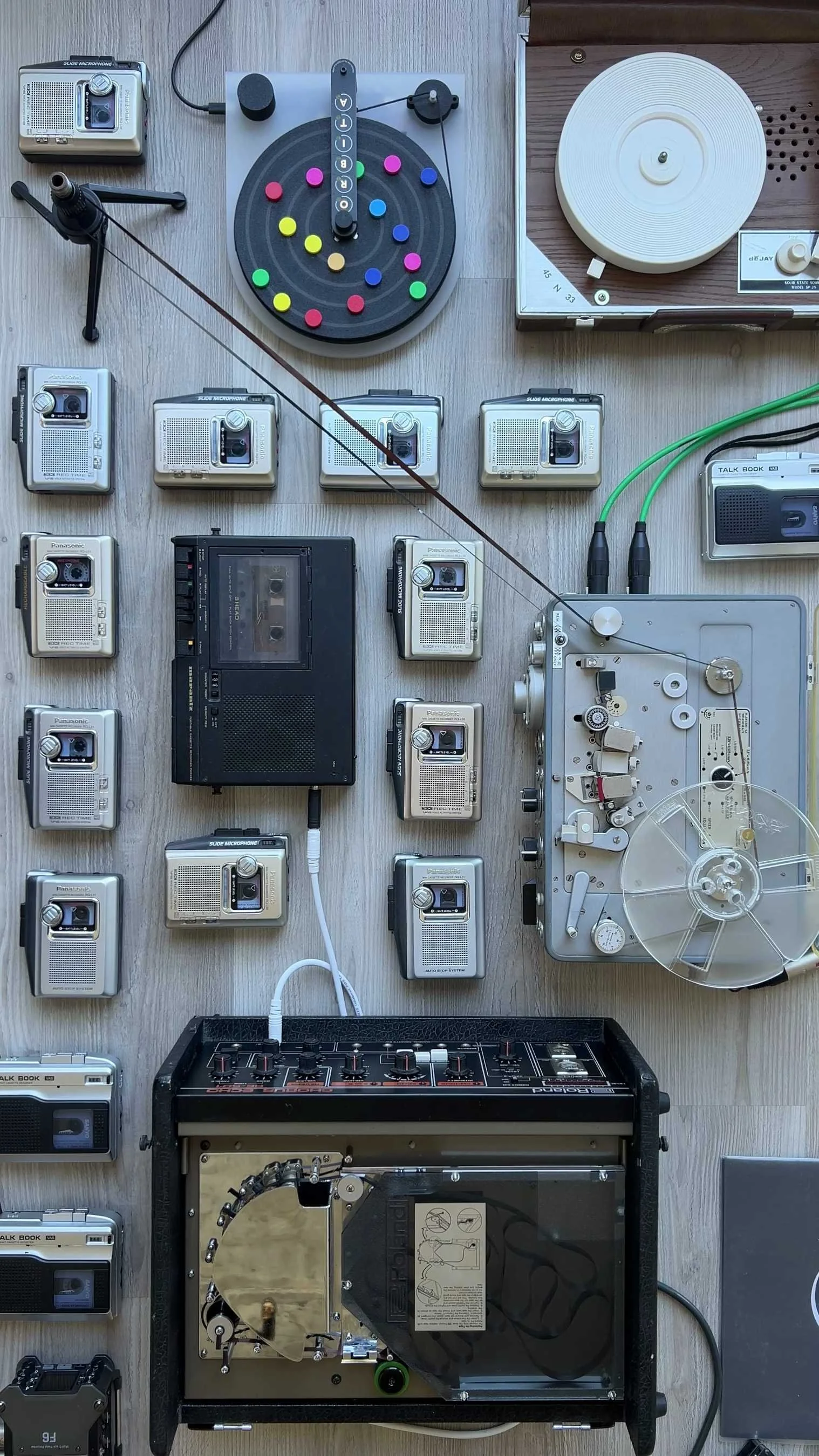

In my soundscapes, you can always hear the turning of reels, tapes, these noisy machines, clicking buttons, all quite industrial, especially when recorded with close mics.

Was there an important moment that shaped how you produce and synthesise? A eureka moment, perhaps?

Yes, that moment came when I started creating artificial bird songs and placing them in real spaces, building generative soundscapes. It changed my artistic path dramatically. That idea gave me a tremendous push. I remember posting my first video on Instagram, and within the first few months, it started to spread fast. My audience was growing.

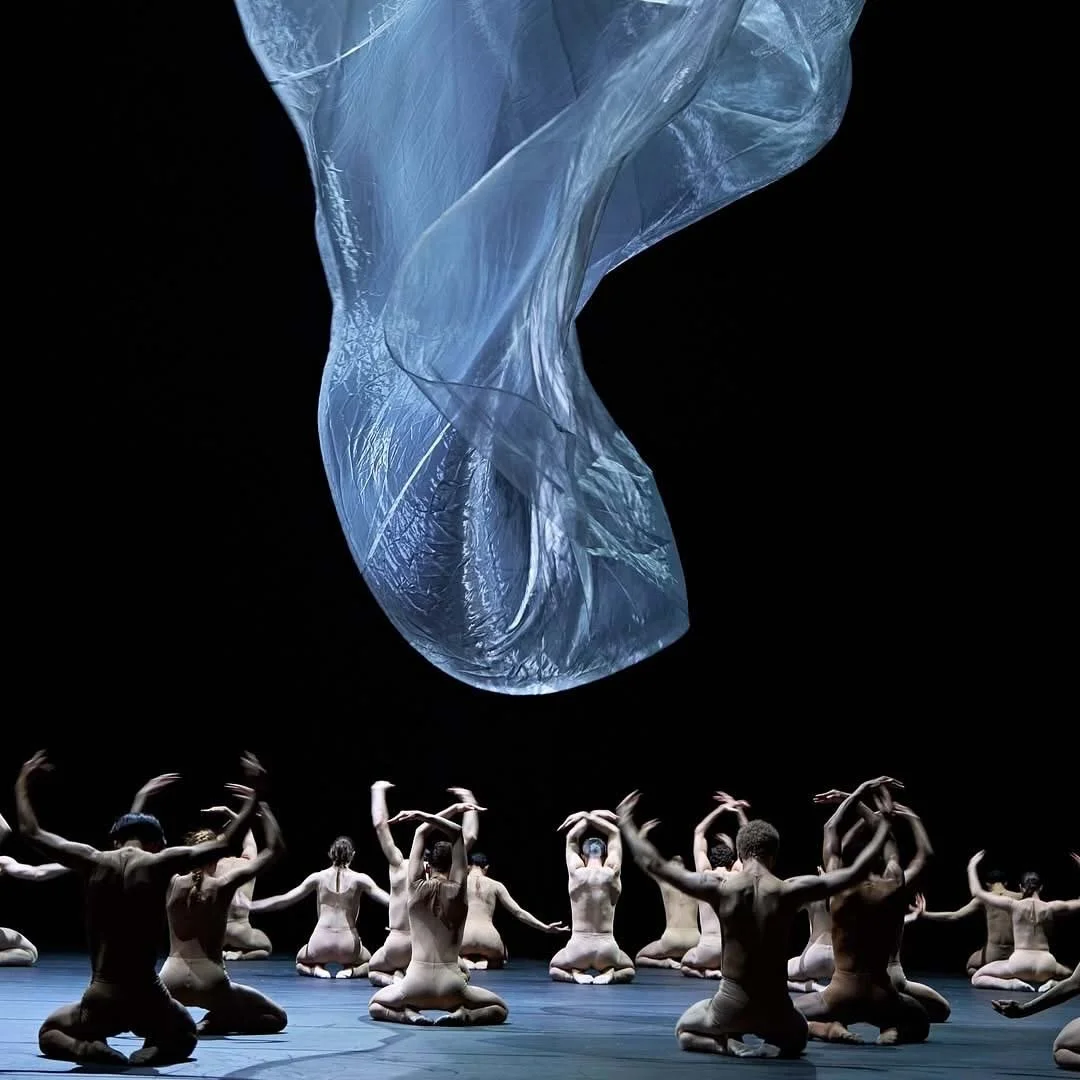

And not long after that, I met Pete Townshend. He invited me to compose a soundscape for his art installation, The Age of Anxiety. I remember sitting behind the screen, having a Zoom call with him, and hearing one of the most legendary artists of the 20th century tell me I’d invented a groundbreaking technique. He said it would influence other musicians, producers, and artists.

That moment shifted everything for me. It gave me a deep sense of confidence and clarity. I felt like this universe I’d started to build was worth growing, evolving, expanding. That was the beginning of a new phase in my life as an artist, a moment where I knew I had to keep going.

How do you want your audience to preserve your work? What is your intention and vision?

That’s a really good question. In my work, I try to share a perspective that there are no real boundaries between music and the sounds of nature. And maybe the most beautiful music was already created long before humans started writing it down.

Honestly, I prefer to listen to a hundred birds in a forest rather than a pop song or a symphony. That’s the most beautiful thing our spirit can experience. I’m not saying human-made music is bad, but for me, nature is where the deeper inspiration comes from. It feels fairer. More real.

When I create generative soundscapes, I try to remove the presence of the human. Even when I use synths, pianos, or strings, I shape them so they sound like they were played by nature, not by a musician.

And when I build these sound worlds, I want to share that message with others. I think this space between music and nature is still largely untouched. There’s so much room to grow. I hope to take this little idea and help it grow into something bigger, like turning a small bush into a redwood tree.

What do you think of AI? How do you think AI is shaping or influencing your work? Is there something you want to experiment on?

I use AI everywhere, except in my music. There just aren’t tools yet that feel right for the kind of work I do. Most AI music tools today are designed to replace musicians, to imitate composers, bands, or producers. It all feels like replication. That’s not what I’m interested in.

But I do think this is only the beginning. We now have the data and the power to simulate other environments, even ones that don’t exist. When I created my first artificial generative bird, I was inspired by the idea of an Earth-like planet somewhere in a distant galaxy, a place that most likely exists. I imagined that it could have bird-like creatures, but with completely different sounds, shaped by the environment and evolution of that world.

Now, with all the data we have, we can simulate those kinds of spaces. That idea fascinates me.

Your work is calming, yet there's an undertone of evocative spirit. What do you find unsettling about the world we live in, and what worries you about what comes tomorrow?

Most of the soundscapes I’ve made were created during very anxious times. And I’ve noticed people often treat my music like a kind of medicine. I remember the first day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. My country bombed Ukrainian cities, the reality just collapsed. I opened Instagram and saw hundreds of people sharing my music. They wrote things like, “This is what I needed today.”

And now… the situation in the world feels even worse. There are more wars. There’s a global right-wing turn that’s deeply disturbing. Sometimes it feels like people have forgotten who they are like we’ve forgotten that we’re one species. And speaking of our ecosystem, it’s heartbreaking. It feels like a massive, unstoppable carnage. Nevertheless, I still believe in a better future, but that future demands our action. This is not the time to wait quietly.

Your music bleeds out of genre in many ways. Yet do you feel the need to define or reform it with time? Is there any need for a definition or vocabulary for your art?

Some people call what I do experimental, some say ambient, or experimental ambient. But to me, none of that makes a difference. And if someone wants to come up with a new name for it, I’m fine with that, too.

Last but not least, what are you working on currently? What can we expect this year? Shows to look forward to?

There are a couple of really inspiring upcoming projects I’m working on. I’ve just begun my first art residency, which will take place at Harvard University this fall. It’s a completely new experience for me. I’ll be bringing a sound installation along with lectures. It’s still early, so we’re just starting to set everything up, but I feel this will be something very special. The people I’m working with at Harvard are incredibly open-minded and creative, and that kind of energy means a lot to me.

I’m also working on a really exciting collaboration with Mujuice. It’s a completely new direction for me, because I’ve never really worked on electronic pop music before. It’s probably not something people would expect, but it’s coming.

Interview by JAGRATI MAHAVER

What to read next