Yehwan Song

Yehwan Song (Yen song) is a web programmer artist and graphic designer born in South Korea in 1995 and based in New York. She uses web computing as a tool to create experimental websites and challenge the general understanding of web design.

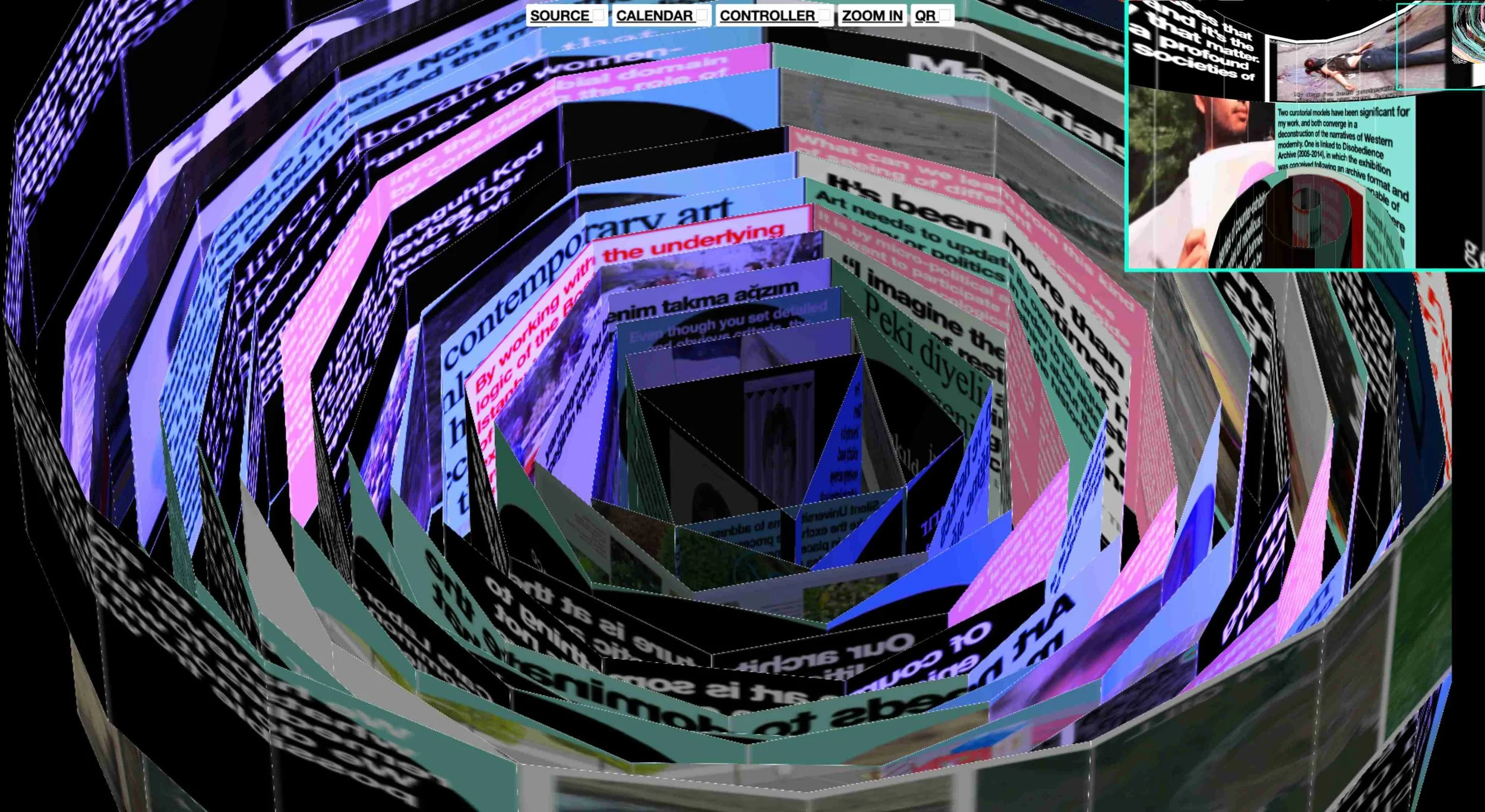

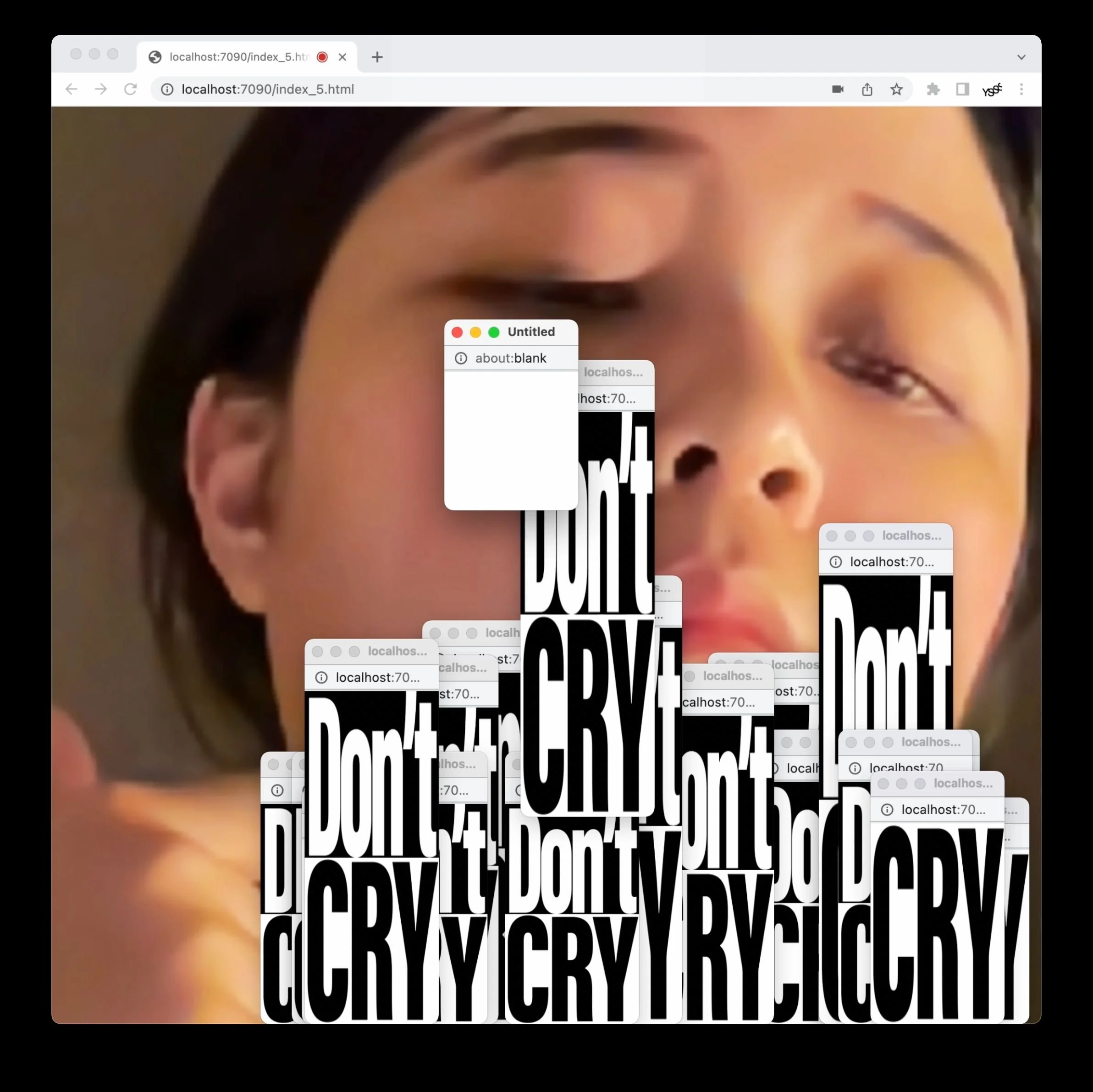

By combining programming and display, she aims to disrupt familiar patterns in interaction and functionality. Yehwan challenges the concept of "User-friendly," the conventions of "interface," and "standardized graphic templates," presenting an anti-user-centric narrative since starting her master’s at the School for Poetic Computation in NY. Through her work, she explores the discomfort and insecurity experienced by marginalized users, often hidden beneath the facade of technological utopianism. With alternative websites and video installations, she reflects on how social inequalities in the digital world become solidified in ideology.

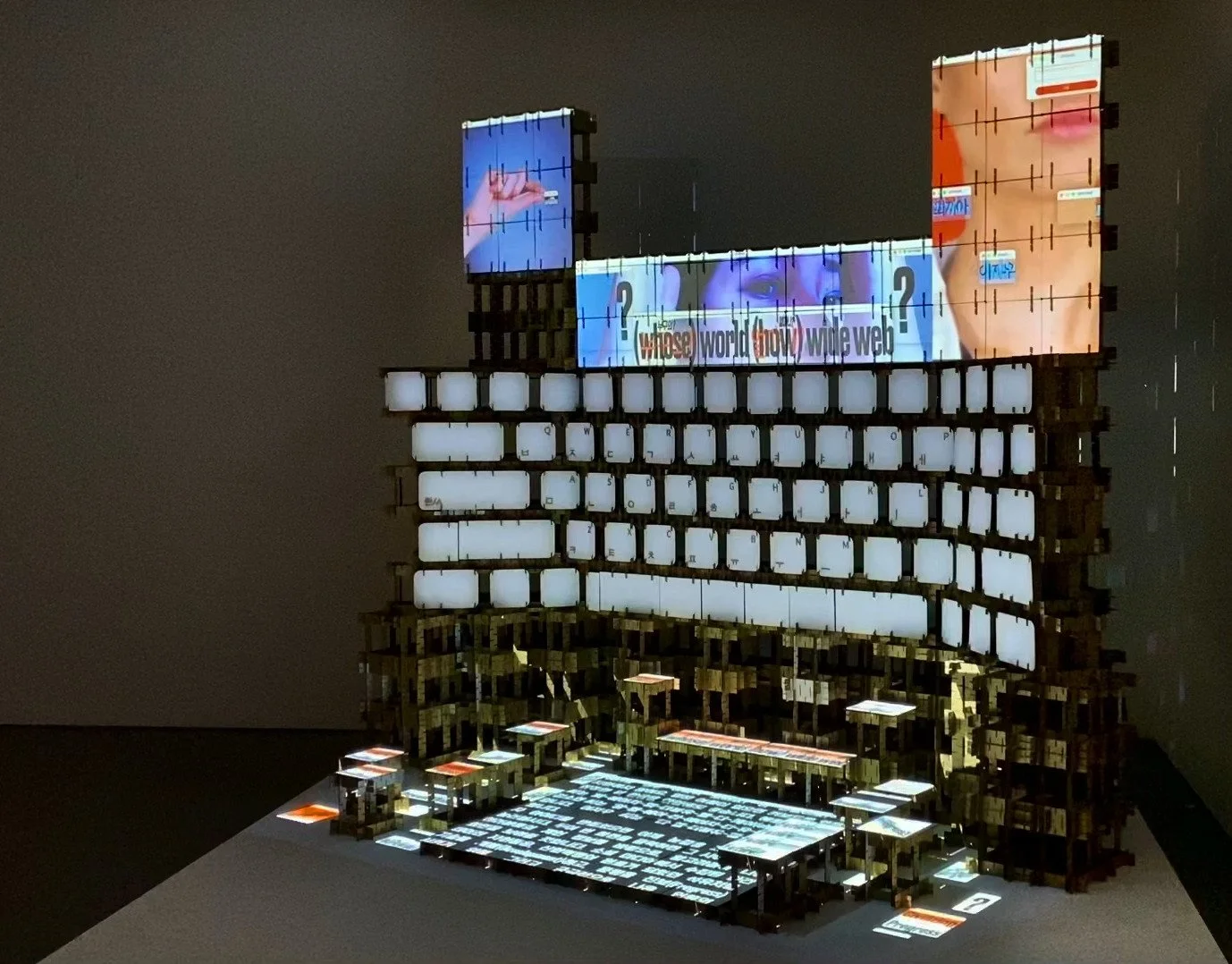

Yehwan's complex installations and narratives materialize digital space into physical inputs, online user interactions, browser performances, immersive generative computational experiences, and new interactions between devices and websites in an anti-user-friendly perspective. Web surfers coexist in a standardized internet ecosystem based on fixed templates: she seeks to reflect on how people use and design websites, addressing issues of censorship, digital justice, and user experience, challenging the notion of ease of use and raising awareness about content. Her art, in a satirical and ironic manner, proposes a more conscious way of navigating the temporary and ethereal world of the web.

In this interview, Yehwan tells us about her artistic practice, and we discuss the government behind the internet and its impact on user interfaces, how it marginalizes non-English-speaking users, web domains, and the awareness of both digital and real freedom for online users.

Hello Yehwan, it's a pleasure, greetings from Milan! Where are you right now, what are you doing?

I’m in New York! Currently working on upcoming exhibitions, performances, and art fairs… It’s been busy as usual

You were born in Seoul and educated in South Korea, graduating in visual communication design. Can you introduce yourself and tell us who you are, how you developed your artistic thinking and practice? How did you get into web design, and programming in general and how did you learn coding?

Yes, I’m from Seoul! I was more of a math kid—especially fascinated by geometry and the beauty of graphs. I loved systems and the aesthetics that naturally emerge from them. When I went to art school, I gradually became drawn to coding, computation, and eventually web design. My curiosity about these systems led me deeper into programming itself. I first learned coding by randomly scraping together information from books and YouTube. Later, I attended the School for Poetic Computation, where I studied under teachers like Zach Lieberman, which deepened my understanding of computation.

What were your initial thoughts and motivations? Why did you embark on this journey to learn codes and web technologies in such a deep, practical, and, above all, conceptual way?

Honestly, there wasn’t a strong initial motivation. It started with simple curiosity—like when you taste really good soup and wonder, “What’s in it?” That was the vibe. I think because of that, my coding might lack a strong technical foundation, but it's conceptually driven. It wasn’t “I need to learn to code → I study coding,” but rather, “I’m curious about how things work → I study in reverse.”

““It wasn’t “I need to learn to code → I study coding,” but rather, “I’m curious about how things work → I study in reverse””

You were born in 1995, which makes you part of Generation Z, a generation exposed to digital devices very early, and thus a natural environment. Do you miss a "pre-digital world"? Do you relate to your generation?

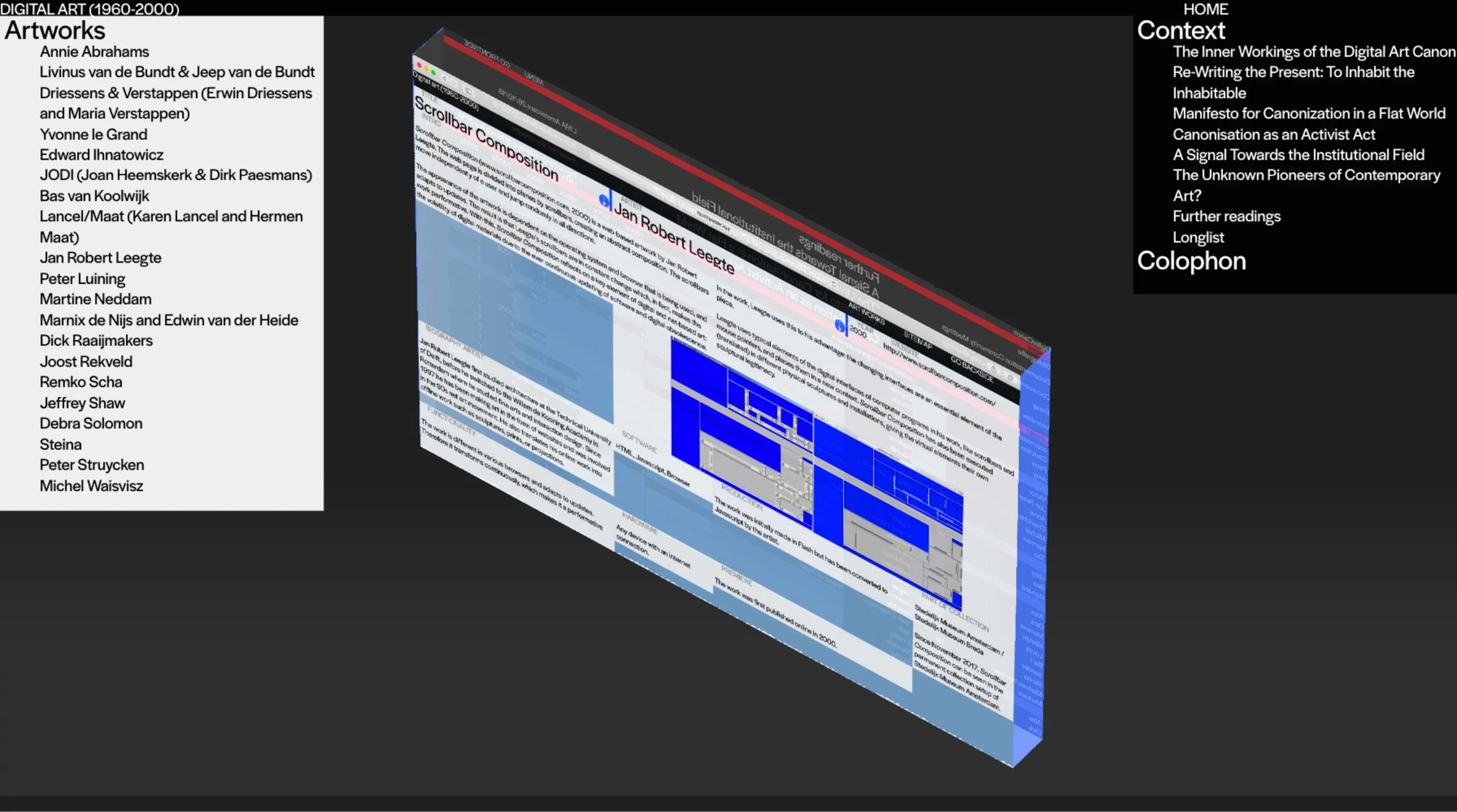

Definitely. That’s what made me fascinated by the history of computers and the early internet, especially net art from the ’80s and ’90s. It was so different from my own experience with the internet and devices. That contrast made me think about the future by understanding history and change, instead of just pursuing future-for-future’s-sake and endless development.

Gradually, from Korea, you developed a hybrid approach between the high functionality of websites and visual poetry. Why did you choose a "temporary" medium, as you define websites and the internet in general?

It’s very temporary, but at the same time, very timely. It’s present, vivid, and ever-changing in a natural way—which I love. I can use it poetically, yet its temporality keeps it from becoming fully abstract.

As you’ve written, your main goal is to explore the discomfort and insecurity experienced by marginalized users, often hidden beneath the facade of technological utopianism, characterized by excessive comfort, speed, and ease of use. When and how did you personally experience this very present form of marginalization?

Lately, I’ve been focusing on linguistic barriers that are so dominant in the internet environment. More than 50% of online content is in English. Programming languages, protocols, documentation, interfaces—all in English. Search engines often prioritize English-language results. As a Korean speaker, I feel how this ultimately marginalizes non-English-speaking internet users.

Escaping from pre-made templates, because they are very limiting: a metaphor for how minorities are misunderstood in the system. Can you tell me more about this? What do you believe is the secret to making the web, networks, and websites satirical, playful, critical, cynical, self-aware? Where is the “loophole”?

I think templates that all look the same—sharing the same systems, icons, and layouts—reflect a standardized view of users: that everyone is the same, with no individuality or preference. By giving everyone the same templates, users are nudged into repeating the same gestures, and over time, seeing and thinking in the same way. I often call this a loophole. I wanted to break that by creating sites that defy traditional templates—as a gesture of questioning: isn't there another way?

““More than 50% of online content is in English. As a Korean speaker, I feel how this ultimately marginalizes non-English-speaking internet users””

Online spaces and physical places: is there a boundary between them, where do you think it lies?

I think of them as a spectrum. It’s not black and white—there’s a long, gray area in between. Sometimes it leans more toward the online with a bit of physicality, and sometimes the opposite.

In South Korea, the country's language isn't used in web technology or domains. The main user-centered, English-based web models make you, as you’ve once described, “very isolated”. How can this be changed through a practice like yours, in web design and web models? How can we make technology more liberal?

Awareness needs to come first. We need to recognize that marginalized users exist. We need to see that the internet is overwhelmingly English- and Western-dominated. So many parts of the world are excluded from what we call the “World Wide Web.” I’m not sure if the internet can ever be truly global and fair. I think that vision inevitably leads to one power forcing others to conform. What needs to change is how we think of the internet—not as a utopian, universally connected place, but as something far more fragmented and unequal than we admit.

When we talk about the internet, we mainly talk about what the big companies present to us as the internet. In Korea, New York, and where you’ve lived, how and with what evidence does this manifest? Do you have a community where you live to talk and compare ideas about these topics? What did you think of Europe during your travels, and what were your impressions? Can the internet be considered an "international environment"?

The internet is very different depending on your geolocation, even in countries considered relatively liberal. Since most major tech companies and social media platforms are based in the United States, there's more critical conversation about the internet in places like New York. There, people are more aware that users can change or influence the web. In many Asian countries, including Korea, people tend to be more accepting of the status quo. The idea of changing tech feels more abstract, especially when tech companies feel far away. I really want to change this dynamic—that’s why I focus on these issues when I have a show or give a talk in Korea.

In the contemporary art landscape, how do you see the role of politics in art? How do you think art can respond to these moments of collective tension, and what do you think could be its impact on the audience?

I think politics and art are similar in that both are about voices, thoughts, suggestions, and ideas—not necessarily solutions. That’s why art can be a powerful medium to support, criticize, or question political gestures in a timely way.

The internet itself is very political. Its structure changes drastically depending on the government behind it. My work is about recognizing these political differences and raising awareness that what you see online never truly represents a global perspective.

In your most recent works, you seem to use a more disenchanted and critical view of reality. What message do you want to communicate regarding the challenges of our contemporary society, and what changes do you hope to see through art?

Diversity over efficiency. Awareness over speed. Human rights instead of turning people into products—these are values we’re sorely missing in both society and tech.

You have these methodologies developed for yourself, such as the "Anti User-Friendly" approach. How would you explain the process of finding that type of artistic framework and vision, defining it, using it, and also what needs to be done?

The Anti User-Friendly project intentionally avoids user-friendly design strategies. Those strategies are based on the assumption that all users are the same, which marginalizes minority users and can lead to a form of digital colonialism. The project is a collection of performances between unpredictable websites and users—meant to spark doubt and break the notion of "user-friendliness."

““Diversity over efficiency. Awareness over speed. Human rights instead of turning people into products—these are values we’re sorely missing in both society and tech””

Alternative websites, video installations, web surfing, and installations: how are the displays of your works designed? Your complex and interconnected structures, which somehow visually materialize the concept of a network navigator, a castaway of the network, can we say it like that?

Yes! Each work has its own methodology and intention, but overall, it's more about visualizing ideas and content—like the experience of navigating a network—rather than following conventional formats.

I really appreciate this conversation! Lastly, I'd like to ask you, what is your view on digital archives?

I always fail at it, haha. I believe the web is ever-changing and temporary, which makes it inherently un-archivable. But still, as an artist and human, I want to preserve it somehow.

Interview by MATILDE CRUCITTI

What to read next