Andra Ursuţa

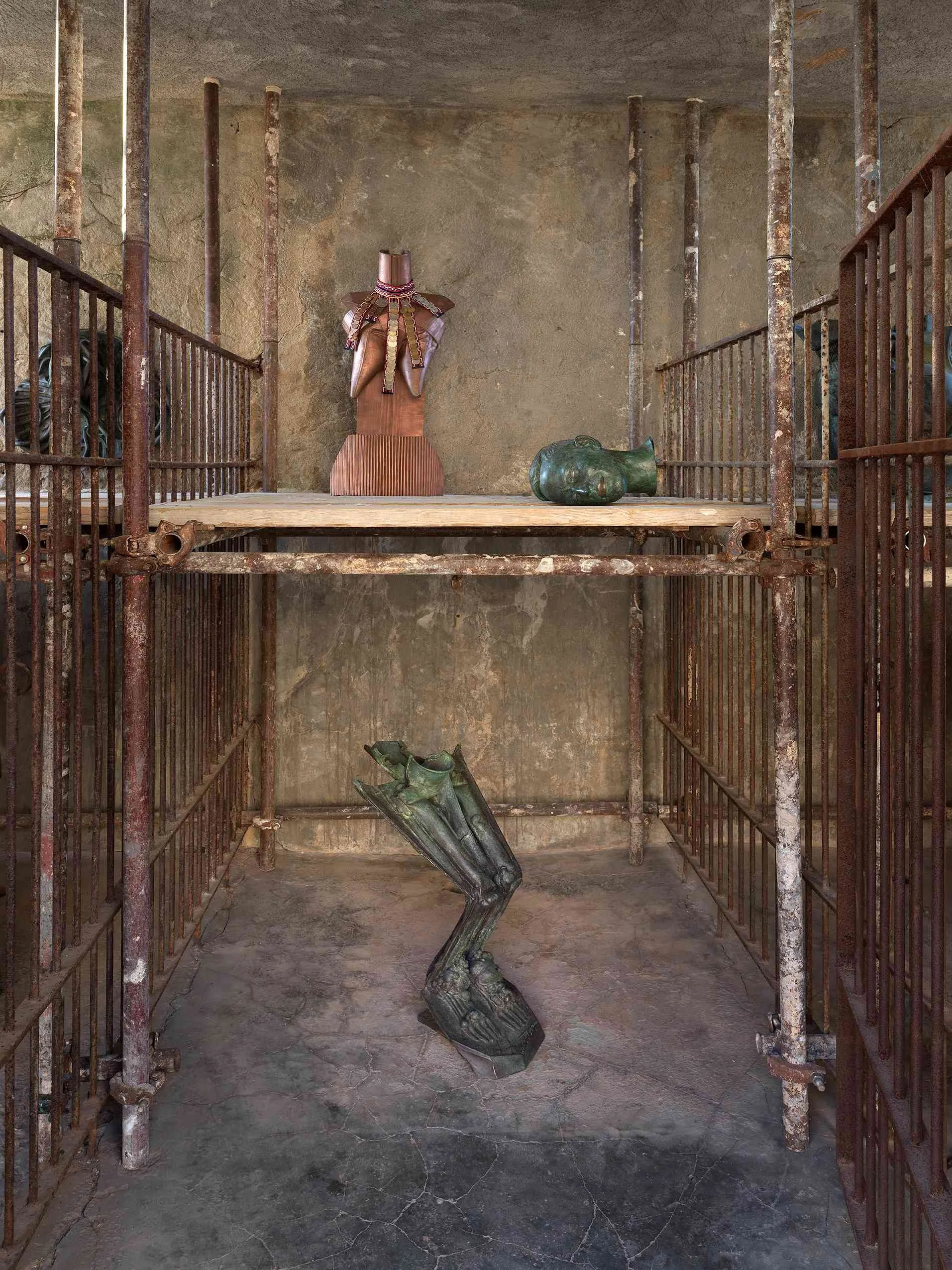

Exhibiton View Andra Ursuţa: Apocalypse Now and Then

In Andra Ursuţa's work, matter twists, implodes, becomes an oracle of a distorted, raw, deeply human present. Her sculptures, hybrid bodies, everyday objects transformed into post-apocalyptic relics, are open wounds that reflect on the dynamics of power, identity, fragility and the desire for transcendence.

Born in Romania and moved to New York in the 1990s, Ursuţa brings with her an acute sensitivity to displacement, trauma and cultural heritage, but without ever succumbing to didacticism. Her works do not explain they insinuate, disturb, speak in physical enigmas.

In Apocalypse Now and Then, the exhibition held at the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art in June 2025, the works do not merely occupy the space: they challenge it, contaminate it and evoke it as a place born for a purpose other than exhibition.

I would like to start with the title of the exhibition: Apocalypse Now and Then, which evokes a “recurring fantasy of the end”. What does confronting the idea of the apocalypse mean to you today? Is it a destructive thought or a way to renew your vision of the present?

I find it an interesting concept to reflect on, especially today, as we seem conditioned to live in a constant state of catastrophe. The original idea of the apocalypse was perhaps a contained event where everything collapses. In the Book of Revelation, there's this image of Judgment Day, where the sky is rolled up—like the world is a flat projection God simply rolls away before moving on. There's a sense of closure in that, something we lack in our complex reality. That's why I believe we must constantly adapt to new apocalypses—face one, then prepare for the next. I'm interested in what it means to live in this ongoing state, where you feel stuck yet continue moving. It becomes a permanent mode, affecting us psychologically and culturally. We suffer in unfamiliar ways, often without knowing why. I'm especially drawn to cultural discrepancies—like how in English it’s the Book of Revelation, suggesting insight, while in Greek or Romanian it’s called the Apocalypse, which lacks that implication. This misalignment in translation intrigued me, because the term “revelation” implies that you will learn something about why things are going wrong. But the concept of apocalypse does not imply this at all.

The choice of location, a former slaughterhouse on the island of Hydra, has a strong symbolic impact: how does this space integrate and interact with the title and content of the exhibition?

The title comes from a series of works I created for this location, inspired in part by the space itself. The fact that it’s a former slaughterhouse was crucial in shaping what to include in the exhibition and the atmosphere I wanted to create. This space is truly unique and, in a way, very stimulating. I prefer exhibitions like this because I find the idea of a “white cube” gallery, where works are placed neutrally and could be anywhere, absurd and boring. I don’t like white pedestals. It’s easier to exhibit here because the space’s uniqueness can’t be replicated. If you miss the show, you miss it forever.

But this also means a completely different way of conceiving the space. I think that, ironically, precisely because very sterile spaces – such as galleries – impose a precise aesthetic, we end up constructing a narrative around the works that is sometimes forced. Much is predetermined: you expect an art show, which makes things easier but less intense.

Here, the place itself isn’t meant for contemplation; it was created to kill animals. If you think about it, it's pretty horrible: it's not a space to be in at all. It has an efficiency unrelated to simply “looking.” It’s a disturbing space. There’s also a direct parallel between the slaughter of animals and their necessity for food. While I’m less focused on the ritual aspect, it’s still present. I think many of the exhibitions held at the Slaughterhouse over the years have addressed this issue. It's inevitable. And I think my exhibition also implies it, albeit implicitly.

It is interesting how a place can have different levels of meaning, and this makes me reflect on the fact that museums and archaeological sites are a source of inspiration for you. Your works sometimes seem to come from an extinct civilisation, but they clearly speak to the present. What kind of “truth” do you think can be expressed through archaeological fiction?

I don’t know if it's true, but I find it interesting to consider how the display of historical objects changes over time, reflecting shifts in our attitudes. In the 19th century, for example, Winckelmann claimed that Greek statues were originally white, which led to an entire body of scholarship based on that misconception. Even though it was factually wrong, it still produced meaningful insights—though we wouldn’t necessarily call them "true." These ideas gained critical mass, forming a kind of truth, but they remain fictional in some sense. When I visited Pompeii, I was more drawn to the outdoor storage cages than the indoor exhibitions.

There's so much archaeological material that much of it can't be shown inside, so it’s stored outside—sometimes even with casts of bodies among the artifacts. That uncurated space felt more compelling to me, almost like the objects were already present without needing formal exhibition. Fot this show I thought it was more interesting for me to use this outdoor space, because it's not really an exhibition, but it's as if the material was already all there. I wanted to recreate here that feeling—placing sculptures in a semi-outdoor setting where they’re less confined by aesthetic or institutional order.

Obviously, there is an aesthetic consideration, but it is really less determined than when the works have already been catalogued and classified, or when someone has decided that they belong in a certain place. This looser arrangement relates to the fragmented forms in the work—many of which resemble amputated body parts. Do these fragments suggest an ideal body, albeit a monstrous one? Or are they simply parts, disconnected from any whole? I don’t know what the full picture is. The idea of a historical museum today feels increasingly uncertain. Much of what we believe about the past is really just a narrative we’ve constructed to link disconnected pieces—not the actual truth.

“We want it all to be real because it’s incredible and we’re so tired of the daily routine, we’ve seen too many images. So, we want everything that’s crazy to be absolutely real. ”

Here you present a new series of bronze sculptures alongside works in glass and other media: How do you choose the materials for your sculptures, and what role do they play in constructing meaning, in tracing a path between ancient and modern, and how do you use them in constructing the meaning you want to convey?

The choice of bronze for this location was very deliberate. I always look to ancient things, but in recent years, in particular, I have been very interested in Etruscan art, and I love the Etruscan Museum in Rome. I think it's a fantastic museum that, unfortunately, is not well known enough. I like to change materials from time to time, and bronze is something I've always stayed away from because it's a bit of a cliché: you know, if you make a sculpture, it has to be in bronze. It's as if everyone who knows nothing about art tells you that if something is made of bronze, then it's valuable. It's art.

So, as a contemporary artist, you immediately want to avoid it. But I like to tackle the very things I'd rather not tackle. I thought it would be an interesting challenge: to see if it was possible to use this overused trope — the bronze statue, perhaps even with a discreet patina, because that's also part of the discourse. Do you understand? Who in their right mind would actually use this solution today? There are probably tons of bronze objects you can buy in shops around here, but for me the interesting question is: can you take this cliché and turn it into something new, or infuse it with a different meaning? That's why I chose to use this material. And also because of the history of bronze sculpture in antiquity, particularly in Greece, because many of our ideas about what art is were shaped by that geographical context.

Following this discussion of materials and processes, craftsmanship is also something that truly belongs to you. Can you tell me about your relationship with craftsmanship and what it means today in an extremely digitalised and industrialised context? How can we consider it? Perhaps we can also look at the idea of craftsmanship from a different perspective. Without always comparing it to the past.

Yes. Today, when we talk about craftsmanship, the term often takes on a different meaning. Ideally, it’s about finding a balance between analogue, handmade processes and digital technologies. Personally, I enjoy working with digital tools. Most of my work includes a digital component. Take the bronze pieces on display: some began as physical objects in my studio, later cast in bronze. Others started as hand-made models, then scanned, digitally altered, 3D-printed, and finally cast. So it’s not always clear-cut—it's not just the artist’s hand at work. Sometimes digital tools reshape manual work, or allow for combinations that would be impossible by hand—or at least not so precise.

These pieces don’t always fit the traditional idea of the handcrafted. While I find purely manual creation interesting, it's not my focus. I don't want to fetishise that idea of craftsmanship, and I think the most interesting aspect of art is not necessarily the visible presence of the artist's hand. It's more about complicating the very meaning of creating an object. I care deeply about making physical works in an increasingly screen-based world. But that doesn’t mean they must be entirely handmade. It's like using AI to write: the point isn't just generating text, but using the technology thoughtfully.

A computer is perfectly capable of writing text that seems coherent, even if it doesn't actually say anything. And for many people, that might be enough — they would stop there. But you can also go further and do something really interesting. So, in the end, it's just a question of understanding where human intervention lies, and how far you want to let the machine go.

This fantasy you resort to, as a reconstruction of a scenario, is strongly reminiscent of the world of cinema, which you draw on. How much does cinema influence the construction of your imagination?

Our lives are increasingly shaped by artificially created images. I think younger generations will face the growing challenge of distinguishing real from fabricated visuals. I already receive absurd videos—like insects turning into flowers—from older friends asking, “Is this real?” I answer, “No, it's AI, How can you think it's real?” but I understand the desire for such things to be real. We're saturated with images and crave something extraordinary. I think cinema has a fundamental role to play in this sense, because it offers an easily understandable narrative of why all this is real, and our brains are conditioned by thousands and thousands of years of consuming stories that lead us to accept it as absolute truth.

But, of course it's essential to separate fictional truth from real-world truth. This becomes especially critical in journalism, where fake news is becoming more sophisticated and common. I also think our exposure to filmic storytelling might impair our ability to decode other visual narratives. Personally, even though I use digital tools, I don’t work directly on the computer. I still draw by hand and pass my sketches to someone else. I prefer this distance—it keeps my imagination open. Knowing too much about the tools can limit you. Sometimes, not knowing leads to unexpected possibilities.

For me, it's better to be a little ignorant and ask, “Could you do this?” And sometimes the answer is no, but sometimes the answer is yes. This approach reminds me of craftsmanship: like asking a carpenter to build something unusual. With glass sculptures, many artisans told me my ideas weren’t possible—simply because they were unfamiliar. But eventually, I found a way. That process of trial, error, and collaboration is powerful.

To conclude: Your works are rooted in something very personal but also universal at the same time. How important is biography to you in the creative process, considering how people can really see themselves in a more collective story?

It's a difficult balance, because I don't think you can start from a completely objective point of view: otherwise you would be a machine, or simply an arsehole. Today, We are all immersed in our fragmented understanding of reality, and there is a lack of real consensus. I worry this fragmentation will only deepen. We need ways to access other people’s realities. In the past, aspects like ethnicity, nationality, class, age, or body type had broader, less rigid contours.

These elements, shaped by personal history, may not always be visible in the work, but they still inform it. I don't think it's very interesting when the work is limited to telling the author's biography. Perhaps this is one of the limitations of identity-based art, which we have seen a lot of in recent years. While it played an important role in giving visibility to marginalised voices, it should be seen as a beginning—not the final goal. Once the “masterpiece of identity” is made, there must be something beyond it. If every work just says “I am here,” it eventually loses impact.

Lately, I’ve felt that identity art can become a way of avoiding deeper engagement with the world. Great artists draw from their unique backgrounds, yes—but they translate that into a language that resonates beyond their own context. And I think the ultimate sign of success is when someone with whom you have absolutely nothing in common somehow manages to be moved or recognise something in what you have done.I think that is, ultimately, the true achievement of art.

What to read next