CreativeTech: A space for future-making

BMW’s with Olafur Eliasson

Creativity is no longer confined to studios, galleries, or research labs, it is being reshaped at the intersection of culture, technology, and entrepreneurship. Within this evolving landscape, two figures are quietly influencing how these worlds begin to speak to one another.

Anastasiia Ageeva, a communications strategist working across Europe’s cultural ecosystems, and Daria Rzhavtseva, an advisor operating where art, tech, and business converge, represent a new generation for whom creative economies function as interconnected systems rather than isolated industries. Their work spans narrative strategy, ArtTech innovation, and cross-sector models that allow artists, founders, and institutions to collaborate with intention.

Google’s AMI program

Together, they co-organised the CreativeTech Cocktail in Lisbon during Web Summit week – a gathering that unexpectedly drew hundreds of founders, investors, and cultural practitioners seeking a shared language for the future of creativity. What emerged was not just an event, but the beginning of a community that understands culture as infrastructure, technology as a catalyst, and creativity as an economic force.

In this conversation for Coeval Magazine, Anastasiia and Daria reflect on the shifting terrain of ArtTech, the business models capable of sustaining cultural value, and the collaborations that could redefine how artists and technologists build together. Their insights reveal a sector in transition, and the frameworks that might guide its next decade.

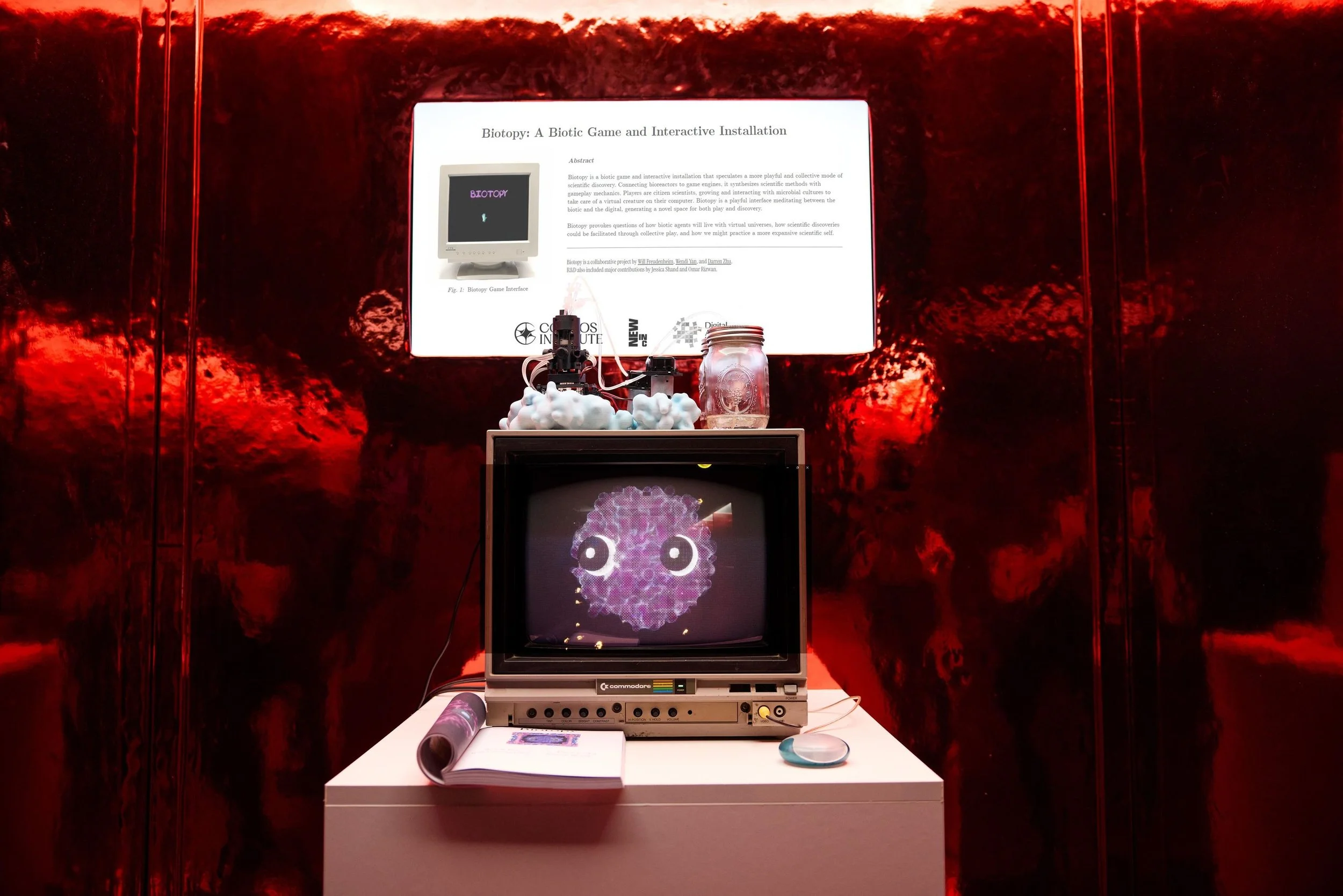

Martine Syms - Neural Swamp

You both come from different corners of the creative economy - Anastasiia from PR and cultural strategy, Daria from the ArtTech and investment side. What was the moment when each of you realised that art, technology, and business are becoming inseparable?

Anastasiia: For me, it happened when I started working with cultural projects and creative tech platforms across Europe - and I suddenly saw the same pattern everywhere: audiences want deeper emotional experiences, companies want cultural value, and artists want new formats and sustainable models. At some point, it became clear that none of these systems can grow independently anymore. Tech without culture feels empty, art without strategy feels invisible, and many businesses without creativity become generic. My work sits exactly at the intersection - translating artistic ideas into narratives that companies, institutions, and wider audiences can understand. That was the moment I realised that communication itself becomes infrastructure.

Daria: For me, the moment came long before I entered the art world professionally. I never romanticised the idea of the “starving artist” or the traditional, almost sacrificial model of creativity. My first education was in Business Development; I come from an entrepreneurial family, so the idea that creativity should be both meaningful and economically sustainable was always natural to me. The real confirmation came when I began working with accelerators and ArtTech founders. Again and again, we helped them define business models, articulate value propositions, and build structures that could scale. And the results were immediate: when creative ideas meet real strategy, funding and impact follow. I also think it’s crucial to distinguish between artists - whose work often requires protection, space, residencies, and grants - and cultural or creative businesses, which must think in terms of P&L, automation, scalable processes, and ROI. These are two different worlds that both deserve attention, but require very different approaches. So for me, art, technology, and business didn’t suddenly merge; it was always clear they were inseparable.

BMW’s with Olafur Eliasson

BMW’s with Olafur Eliasson

Daria, you often speak about making “investment work for culture, not against it.” What business models in CreativeTech do you believe truly create value for culture and creators?

Daria: When we talk about “investment working for culture, not against it,” we have to remember that culture becomes vulnerable when it relies only on charity, and distorted when it relies only on commercial pressure. Real sustainability lies in between. I don’t believe CreativeTech needs unusual or exotic business models. The same models that work in other sectors can work here - the challenge is adapting them in ways that respect the artistic process while remaining economically sound. Whether it’s IP management tools, analytics platforms, creator-focused AI tools, or community-driven infrastructures, value comes from building solutions people genuinely need and are willing to pay for. Another crucial point is preparing the market itself. Many technologies that are standard in the tech world - automation, AI agents, workflow optimisation —-are still new for art institutions. But these tools can make galleries, auction houses, and cultural platforms far more effective, freeing artists and curators to focus on creation. So instead of searching for one “ideal” model, I think the goal is to make the entire ecosystem more sustainable through smarter practices and meaningful cross-industry collaboration.

Anastasiia, from your perspective in communications and art ecosystems: how can companies - even outside the cultural sector - strategically work with art to solve their business objectives?

Anastasiia: First, companies need to stop treating art as decoration and start seeing it as a strategy. Art influences emotions, perception, brand trust, and even wellbeing indicators - I see this directly in projects that use biometric data to measure audience reactions. It also helps companies become more socially responsible, which often plays an important role in legal and government-relations contexts.

What are the biggest cultural blind spots when tech companies try to work with artists - and vice versa? How are emerging ArtTech tools reshaping the way artists and creators work today?

Daria: Whether we’re talking about ArtTech startups building tools for the cultural sector or big tech companies collaborating with artists, the biggest blind spot is the same: many tech teams don’t understand the plurality and complexity of the art world. It’s a huge ecosystem, but also a very relational one - built on trust, reputation, and cultural context. Tech companies often choose the same big-name artists, repeat the same strategies, and overlook the opportunity to build more meaningful collaborations. Real impact comes from long-term relationships, not one-off projects. Tech brings tools; artists bring meaning. But both sides need to understand each other’s logic. This is where our work becomes essential: translating between these ecosystems and helping them build strategies that actually last.

Anastasiia: From my side, the biggest blind spot is misunderstanding how the art ecosystem functions. It’s slow, relational, and reputation-based - not metrics-based. Many tech companies approach artists as if they were developers: fast deadlines, fixed KPIs, no emotional context. And artists often assume tech wants to instrumentalise them.

But when both sides slow down and learn each other’s logic, collaborations become incredibly powerful. I’ve seen creators unlock new forms of expression with AI and other digital tools - and I’ve seen tech companies rethink their identity through cultural narratives. ArtTech tools don’t replace creators; they expand their vocabulary.

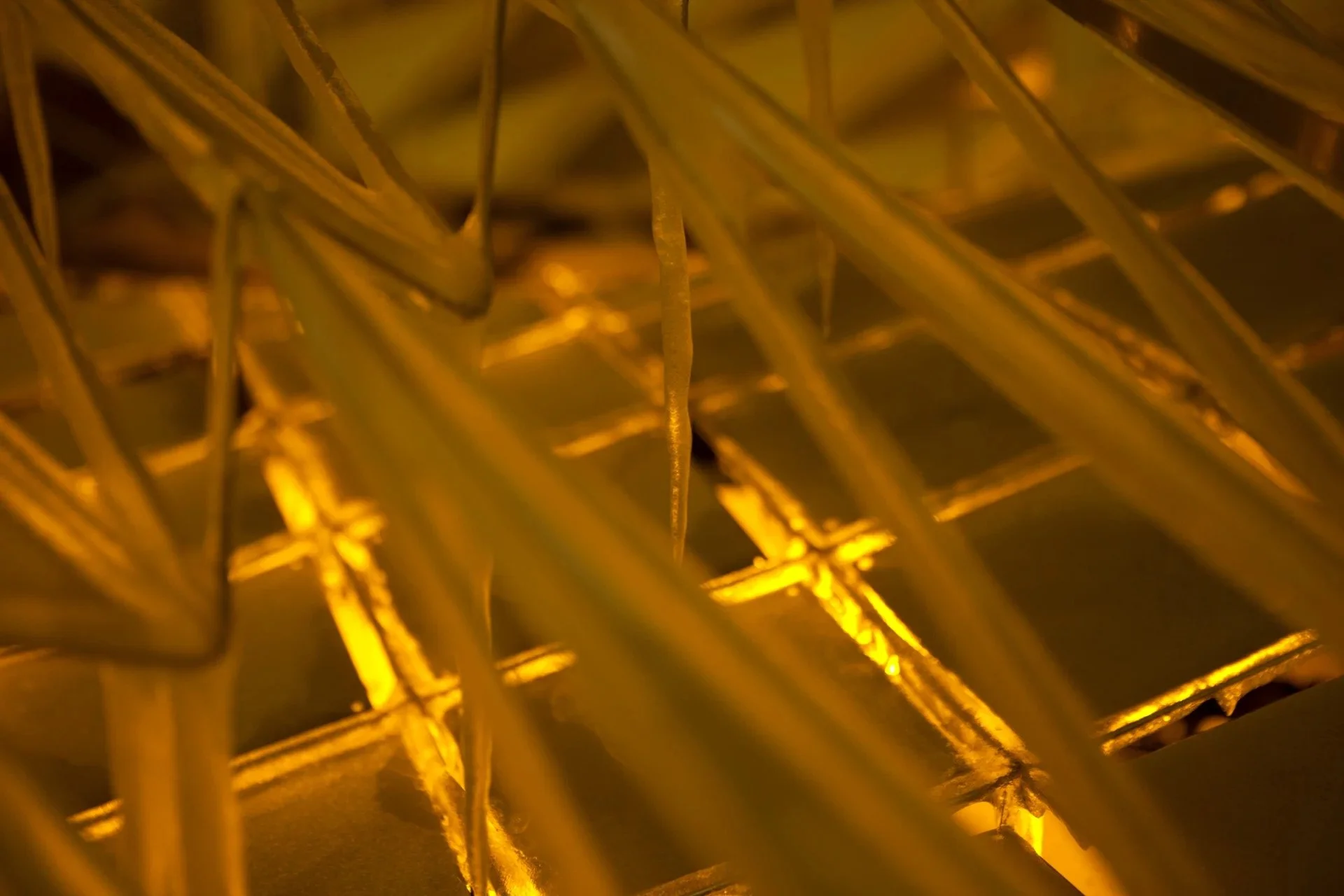

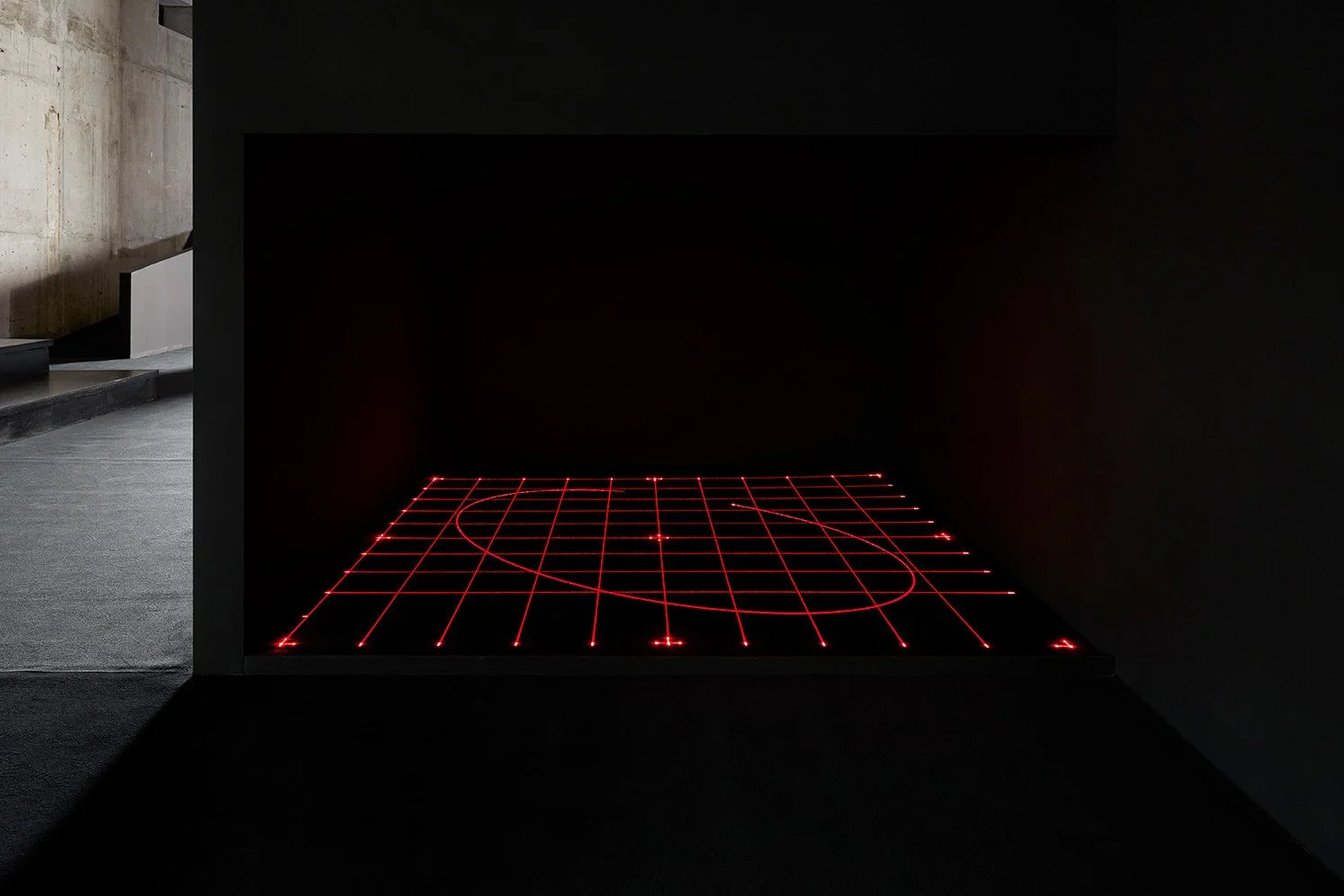

Ryoji Ikeda — Data-verse Exhibited at 180 The Strand, 2021

You organised the CreativeTech Cocktail in Lisbon during Web Summit week. What was the initial idea behind creating a space where artists, founders, and investors meet?

Daria: The idea came from a simple observation: despite all the discussions about creativity and technology, there were almost no spaces where artists, founders, and investors could meet on equal terms. In both the tech world and the art world, there’s a belief that the two ecosystems are too different - or that CreativeTech is too niche to deserve its own community. But our experience showed the opposite. When we launched the CreativeTech Cocktail, we expected a small, curious crowd - instead, we received almost 400 applications. That alone proved the demand. Founders want cultural depth; artists want new tools; investors want meaningful innovation. So our goal wasn’t just networking - it was building a shared language and a shared space for cross-disciplinary collaboration. That’s where the most interesting innovation happens.

Anastasiia: For me, the idea was also very personal. Working across different cities, I saw brilliant people doing incredible work - but all in parallel universes. Art talks to art. Tech talks to tech. Investors talk to investors.

I wanted to create a space where these worlds cross naturally, not formally. A place where an artist can casually explain a concept to a VC, where a founder finally understands the cultural relevance of their product, and where institutions meet innovators without bureaucracy. This is exactly the ecosystem I want to keep building.

Ryoji Ikeda — Data-verse Exhibited at 180 The Strand, 2021

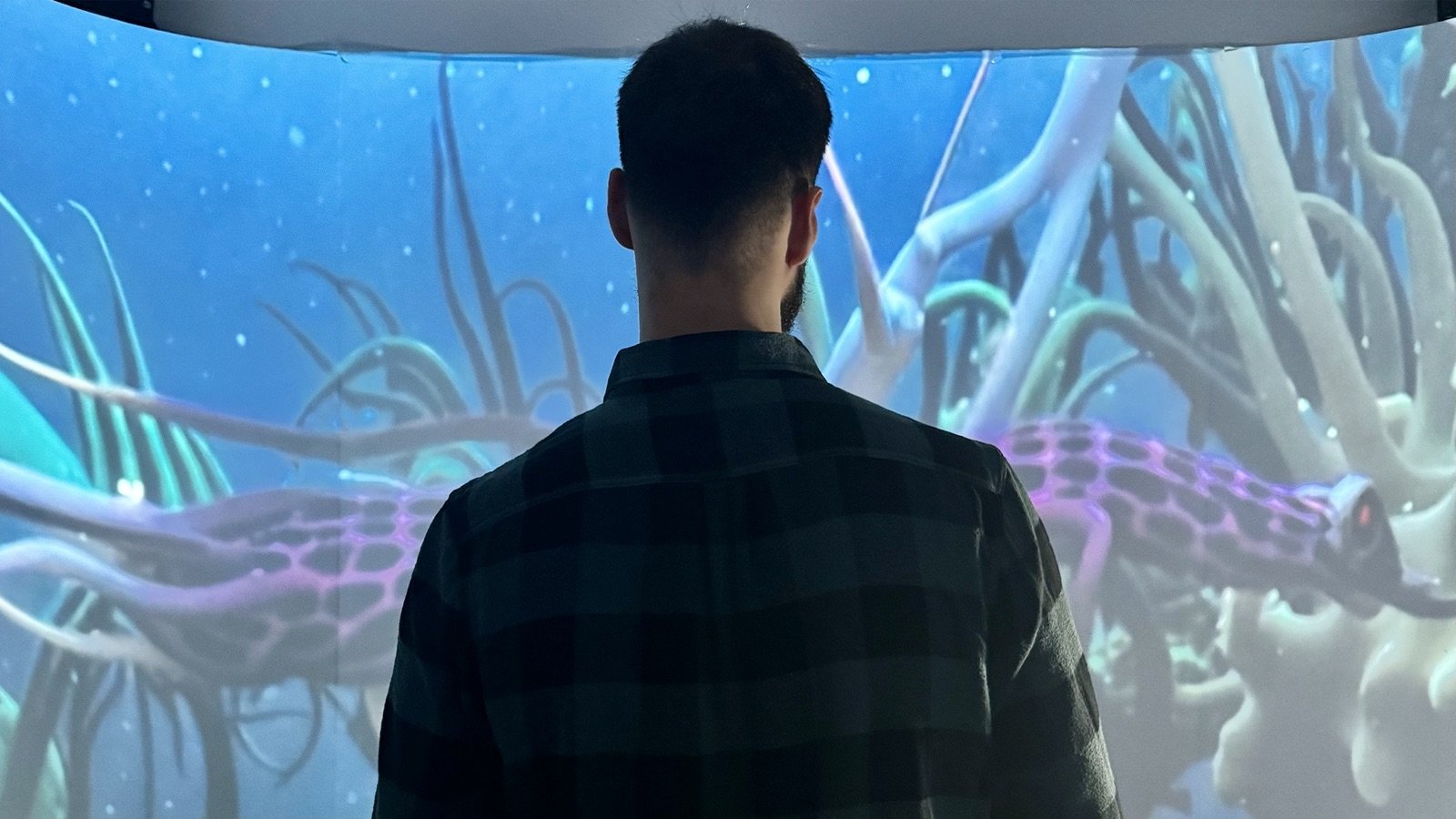

Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised at MoMA

Around the world we’re seeing more collaborations between major tech companies, corporations, and the art world - from generative installations powered by data to artist-led R&D labs. What global practices do you think are the most interesting, and what can companies learn from them?

Anastasiia: If we look globally, the most successful art–tech collaborations all share one principle: artists are treated as co-authors, not decoration. And we already have great examples that prove how powerful this approach can be.

Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised at MoMA showed how AI can turn museum archives into living artworks. Google’s AMI program gave artists access to machine-learning tools and led to some of the earliest iconic generative pieces. TeamLab’s collaborations with Epson and Panasonic turned immersive technology into a global cultural language. BMW’s long-term partnerships with artists - including Olafur Eliasson - showed how brands can support artistic research, not just marketing. And Fondation Cartier’s Data-verse with Ryoji Ikeda remains one of the strongest examples of turning scientific data into large-scale visual experiences.

All these cases demonstrate the same thing: when companies build with artists - not around them - the results become meaningful, memorable, and globally recognisable. This is the direction we explore in our own collaborations.

What to read next