Charlie Thomas

At a joint press conference with the newly elected NY major, Zohran Mamdani, Donald Trump, interferes Mamdani. Trump says in a somewhat humorous manner: «You can just say ‘yes’. It is easier that way». But it’s not a joke.

In her multilayered work the French graphic designer, musician, and artist, Charlie Thomas, connects the current fascist rise with language and semiotics. Studying the far right’s use of words and symbols in their campaigns, speeches, and on social media, her indebt research – echoing Sara Ahemed’s essay «In the name of love» – come to reveal that in truth the far right did not win elections on hate rhetorics, rather they have predominantly been talking about love; their rhetoric is not dominated by their hate of immigrants, but the love of their country, and the necessity of protecting this love object.

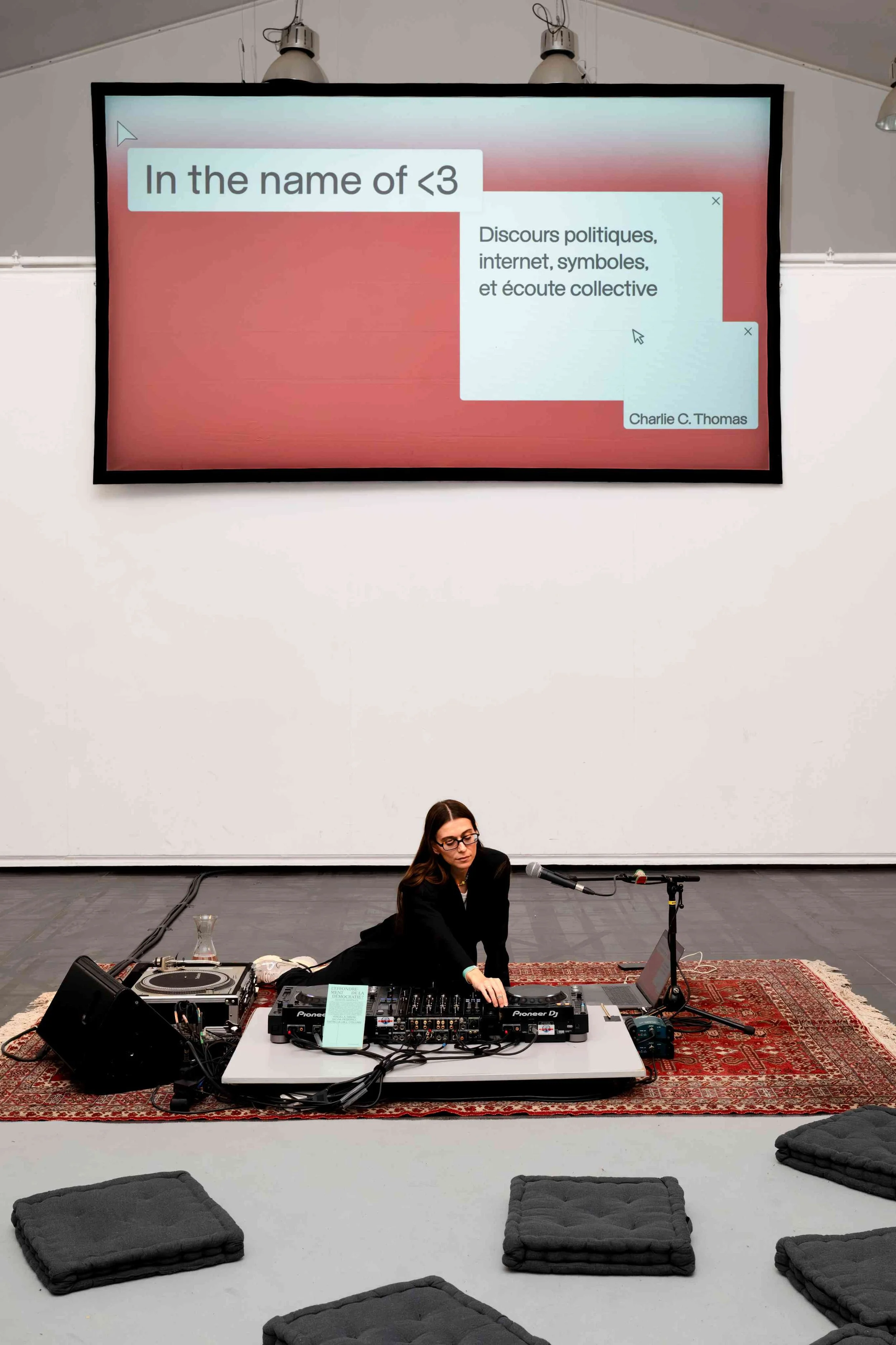

Departing from these ideas, Thomas recently presented the performance In the name of <3 as a part of Art Emergence’s first festival edition, titled What the world needs now, curated by Flora Fettah, Assia Ugobor and Lamia Zanna. In an audiovisual live radio performance, Thomas interlinked the use of heart emojis and love language with the rise of right-wing politics, and thus delivering a contemporary read of Watler Benjamin and Wilhelm Reich’s concept of ‘fascist seduction’.

For more than five years you have been working with the symbol of the heart, what sparked your interest for this specific iconography?

In 2017, I gave a workshop at Re:publica, a Berlin-based digital culture festival. In the aftermath of Trump’ first election, the main theme was Love Out Loud (LOL): Love was used as a tool to fight the rise of the alt-right. Heart symbols were displayed on wooden signs, screens, and flags. The same year, I moved to Sweden knowing very little about Swedish political parties and even less about their visual communication strategies. I first saw banners from the Swedish Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna) on the streets, prior to the 2018 Swedish general elections. White background, a pattern of blue flowers, heart symbols and a cursive font, I interpreted the banners as symbols of peace and love and automatically affiliated the party with the left side of the political spectrum. Sverigedemokraterna is a far-right nationalist political party. Today it is part of the ruling coalition. Like Re:publica, I was using the language of love for my own political opinions. Anything else was hate and must be visually represented as such. In reality, I had taken for granted visual codes like the flower and the heart, thinking nationalist anti-immigration parties were not entitled to use them.

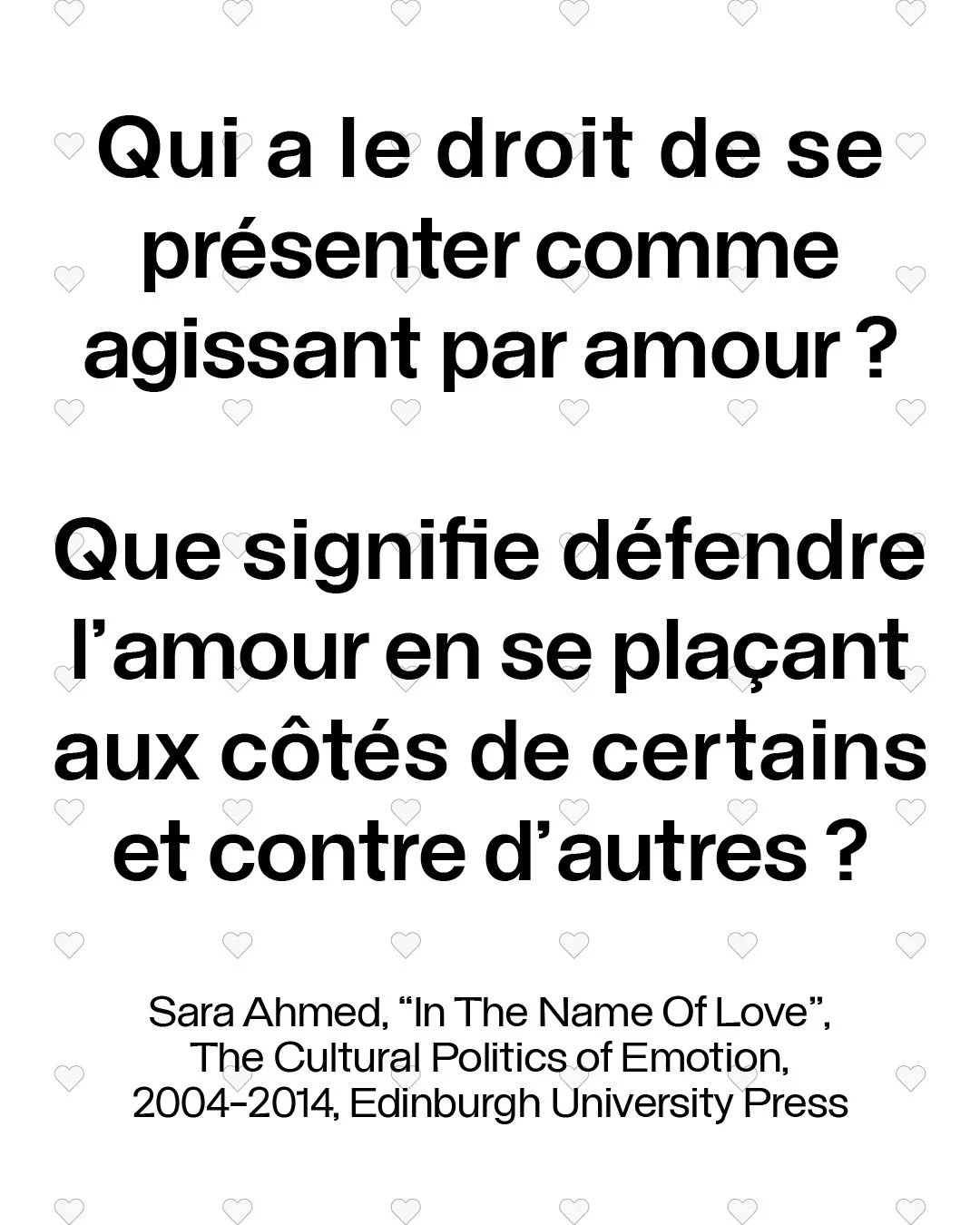

This is how I started the research, asking myself, “who claims love? And why?” which led me to read the text of Sara Ahmed “In the name of love.” After studying ‘hate groups’ renaming themselves as ‘organisations of love’, she exposes the misconception that love is only used by one side of politics and belongs to a single ideology. The text was first written in 2003, so I decided, based on her research, to continue exploring the use of love within the context of our digital spaces and the hegemony of social media, focusing specifically on the use of the heart symbol.

In our present-day techno-infused reality, the heart – or cordiform – has increasingly come to represent our life on social media, where likes act as a tool for targeted advertising and the collection of data. How do you think this development has altered our perception of the meaning of the symbol?

The heart symbol is a button, a click, a double-tap, a reaction, and the most popular emoji. It is incredibly easy to use or send, and it has become an automatic gesture we don’t even think about anymore. We don’t “love” everything we see, most of the time it is just our way of saying “I’ve seen this.” Ultimately it’s just a marker.

The problem is that this marker, the heart, leaves constant traces of our connections and interests, and it triggers an almost endless chain of data collection, in a market place that remains completely opaque to us. It’s also training models and predictions we have zero control over.

My point is that the symbol itself carries so much more than we can possibly comprehend, so we keep tapping and scrolling on our phones. What’s invisible to us is really hard to tackle. I’m pretty sure if we had a clear map of where our likes actually end up, we would stop using the heart symbol altogether.

Departing from the work of Sara Ahmed, you have presented both a publication and a lecture performance under the title In the name of <3. Both are dedicated to exposing the strategic use of what you define as «love language» by the extreme right. What does this entail?

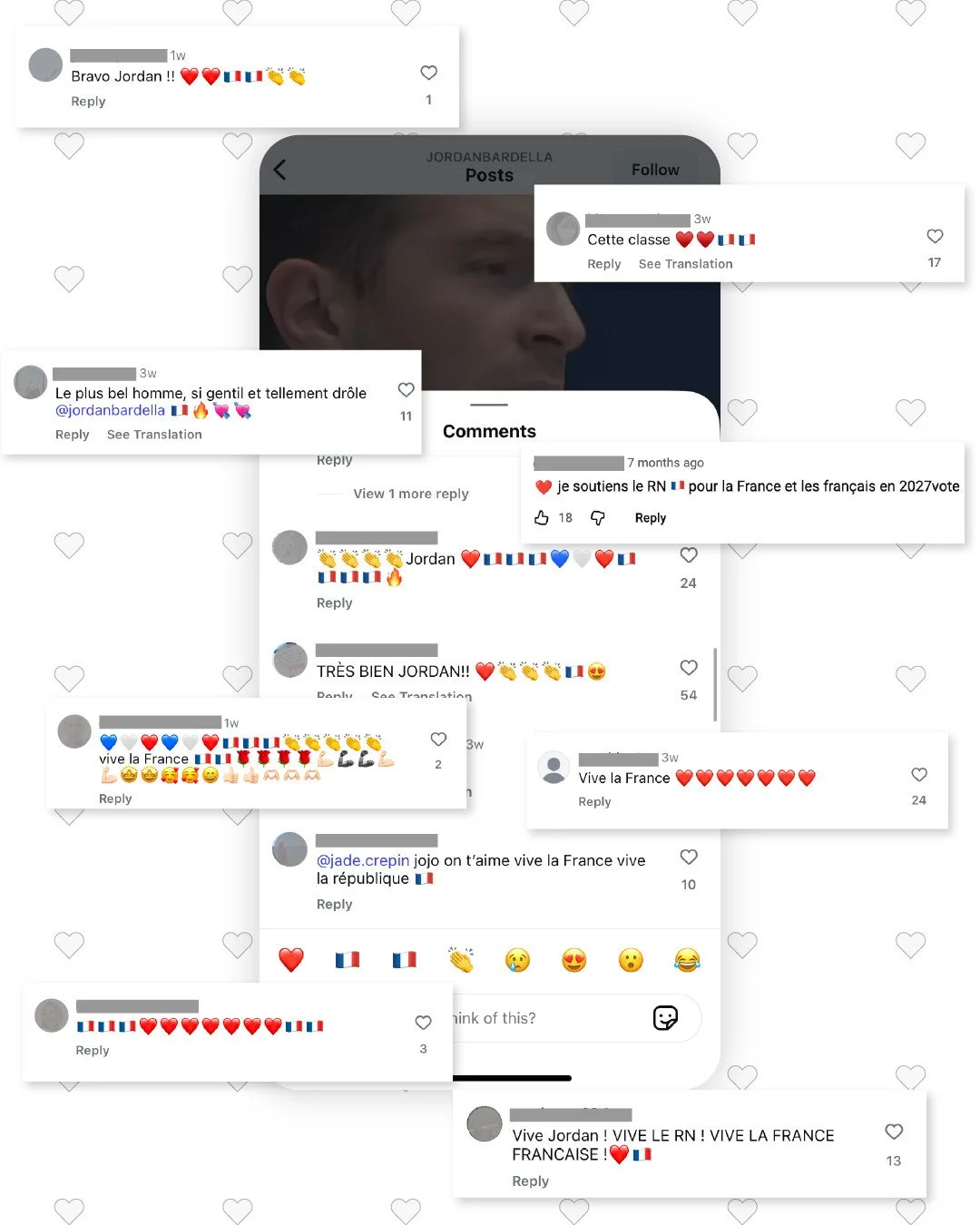

After reading Sara Ahmed’s research, I started by looking at what is the most visible in far-right communication: logos, branding, street banners and posters. The use of the heart increased over the years, and it really proves Ahmed’s point about how emotions can be strategically mobilized in political language.

From there, I moved into the aesthetics of social media. I spent time in comment sections, looking at how far-right groups use the visual and linguistic codes of mainstream platforms to appear relatable and ordinary. They adopt the language of care, community, and affection to create a sense of belonging. And what becomes clear is that it forms a full circle: affects work extremely well on social media, they travel faster, they boost visibility, and they trigger a whole chain of algorithmic scoring. So this angle starts to reveal the interdependence between capitalist platforms and far-right strategies.

In other words, what I’m exposing is how the far right strategically uses the aesthetics and affective language of “love,” amplified by social media infrastructures, to normalize and circulate their messages.

“I’m pretty sure if we had a clear map of where our likes actually end up, we would stop using the heart symbol altogether.”

What role do you believe the application of love strategies play in the current rise of the right and authoritarianism?

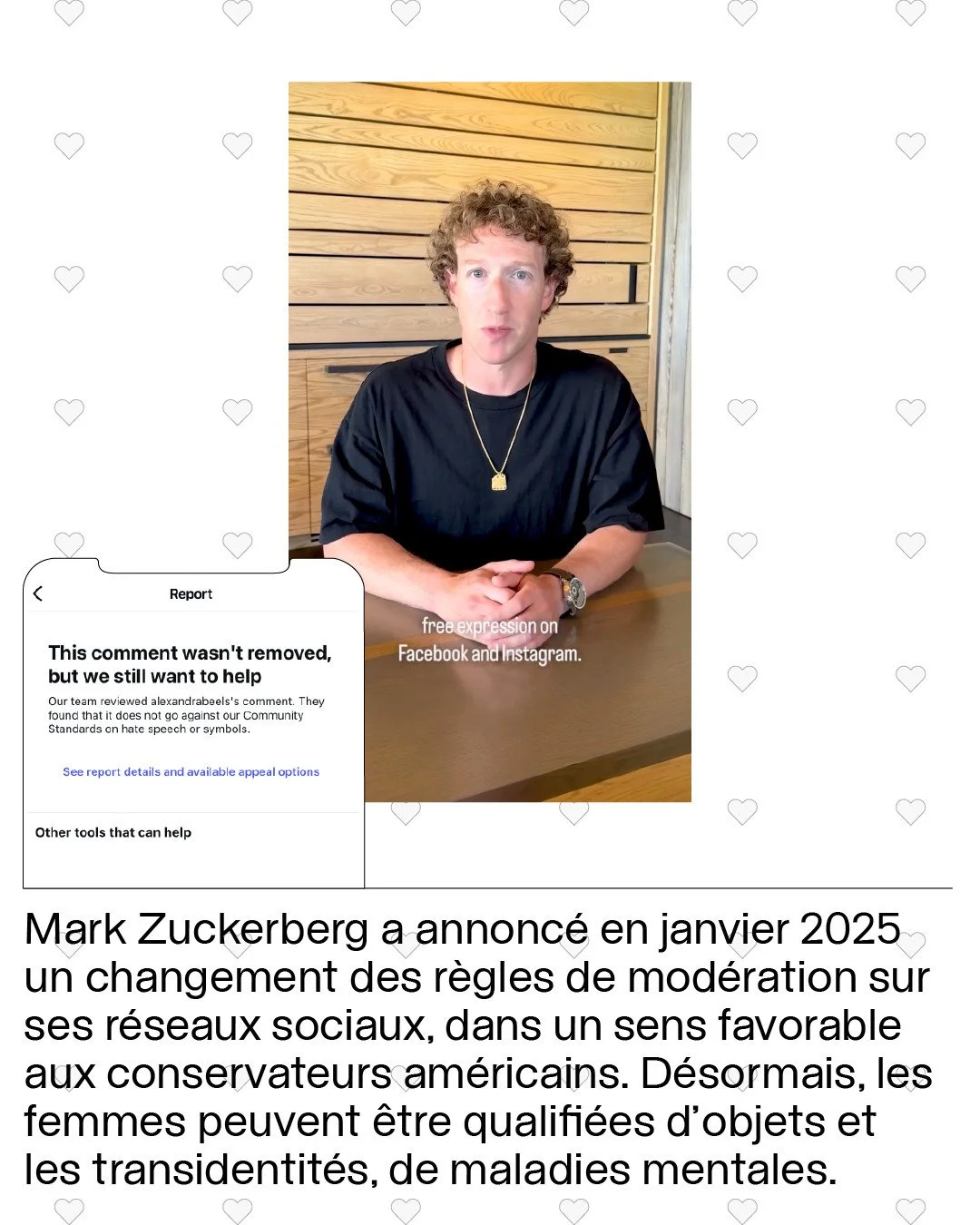

When the far right adopts the visual and emotional codes of love, care, or protection, they’re exploiting the digital attention economy to circulate messages that appear positive or inclusive, while actually reinforcing systems of hatred, exclusion, and control. It’s a way of softening the edges of authoritarianism.

This strategy also goes hand in hand with the instrumentalisation of bodies and identities, especially women and LGBTQAI+ people, who are used symbolically to project an image of openness or progressiveness. But in reality, these same groups are marginalised by the policies being promoted. Sara Ahmed writes about this very clearly in The Cultural Politics of Emotion: how “love” becomes a normative affect, a tool for building identity cohesion that ultimately excludes rather than welcomes.

We’ve seen how effective these strategies can be. In 2016, the far right and alt-right managed to install key figures in power by recycling mainstream slogans around “love”, sometimes bringing gay cis men influencers, only to defend anti-trans and anti-immigration agendas. They use the love of the nation, the love of their “people”, as a justification for border violence and exclusion.

What’s striking today is how mainstream all of this has become. Even when far-right parties aren’t formally governing, the parties that are in power have absorbed major parts of far-right ideology, especially around immigration and anti-lgbtqai+ discourse. In France, for instance, figures like Bruno Retailleau [former Minster of Interior in France] have normalised far-right language under a different political banner. This is why authoritarianism is already in motion: it doesn’t need to announce itself as such.

And now we see another shift. While the far right still uses the language of love, they’re increasingly leaning on words like “freedom,” “protection,” and “defence.” They’re circling back toward a more militarised vocabulary, which suggests that the love strategy has already fulfilled its purpose, it opened the door. Now they’re consolidating the narrative.

So the role of these love strategies is really about normalisation: using the language of affection to make authoritarian ideas feel familiar, reasonable, even caring. And once that groundwork is laid, it becomes much easier for more openly violent or controlling discourse to take its place.

If the opposing parties were to challenge the right wing’s use of love language, what language do you believe they should apply?

I think the main challenge with responding to the far right’s love language is that language itself is unstable. Words and symbols can shift meaning very quickly, and the far right is skilled at appropriating them. Terms like “freedom,” “protection,” or “love” are constantly redefined and reused to justify their agenda. And we’ve also seen new terms appear out of nowhere like “anti-woke,” in France, which conservative media have managed to impose in public debate.

So I don’t think the answer is for opposing parties to invent a new language, because whatever language they use will inevitably run the risk of being reappropriated as well. The real challenge is elsewhere: it’s about reminding people of the historical roots and continuous dynamics of fascism, exposing its tactics, and building strong chains of solidarity against it. We need more courage in the media spheres that claim to oppose the far right, but also in everyday life, everyone, regardless of their background or profession, should feel legitimate in resisting these forces.

I don’t pretend to have a ready-made solution, but I can speak from my own practice. My way of responding is to use my work to monitor media narratives, to expose the far right, and also to expose everything that contributes to normalising far-right ideas. That’s the set of tools I’ve chosen.

“When the far right adopts the visual and emotional codes of love, care, or protection, they’re exploiting the digital attention economy to circulate messages that appear positive or inclusive, while actually reinforcing systems of hatred, exclusion, and control.”

Your performative work moves between lecture, music and moving image. The result is audiovisual, and surprisingly intimate. How do you see these three disciplines in relation to one-another in your work?

This performance stems from both my work as a graphic designer and as a music programmer for the radio. I make presentations weekly in my work as a visual designer, to explain the process and show final results. That shaped the lecture aspect of the performance, but I didn’t want to “just” give a talk. Radio taught me something different: the importance of listening, of bringing artists together, and of giving space for emotion. Sound has an immediate intimacy.

When I was invited to perform at La Maison des Métallos for Art Émergence, I honestly didn’t know what the final form would be. But I knew I wanted to create a moment capable of disarming the violent images and narratives of the far right. Since the performance deals with the idea of reclaiming love, I wanted to craft something intimate, something we could share collectively, almost as a way to resist the theft of that emotion.

So I imagined the whole performance as a collective listening moment, like recording a live radio show. People were sitting on the floor, close to me, almost like being together in a living room. That format feels natural to me, it lowers the distance with the audience.

Visually, I wanted to echo the images we had just seen but without reproducing their violence. I started to distort them, using morphing, shifting colour palettes, so the same documented images became abstract. They lost their solidity and their authority. In a way, I wanted to undo what we had just witnessed, to soften and disintegrate these images.

For me, lecture, music, and moving images are tools that let me move between explanation and emotion. When they work together, they can create a space that feels both critical and intimate, and that’s the space I want to invite people into.

I also want to credit Flora Fettah, a Marseille-based art curator with whom I’ve worked on several projects. For the past few years, we’ve been thinking through this research together, translating it into French, but also exploring how to present it in new forms. Her external perspective has been essential in shaping this performance.

Interview by UNA GJERDE

What to read next