Tirana Art Weekend 2025

The second Tirana Art Weekend, developed through the Albanian Visual Arts Network and curated by Arnold Braho, mirrors this character by engaging with the city as a volatile field of forces. The November program brings projects and performances into contact with a landscape where new towers compete with fading facades and vacant lots carry a sense of suspended anticipation. This terrain rejects stable meaning. A dense Balkan atmosphere circulates through every street and corner.

Rather than arranging order, Tirana Art Weekend draws attention to the raw condition of the city. Tirana follows its own logic. A past with political fractures flows beneath current shifts in architecture, culture, and social life. Growth proceeds in unpredictable bursts. Contradictions accumulate and produce an environment that feels alert and unfinished. Life often begins in peripheral areas, in pockets where institutional attention has not yet settled.

Within this framework, the project Re-enact a Fable investigates the mechanics of the fable as narrative structure and cultural instrument. Patterns of repetition, the presence of the double, and the pedagogical dimension of storytelling serve as foundations for the participating artists. They rework memories, diasporic experiences, fragments of collective life, and independent modes of organisation. Through these gestures, the fable becomes a method for interpreting transformation and conflict. It functions as an open system that adapts to shifting temporalities and social changes.

The program stretches across several venues, each carrying its own history and symbolic charge. Villa AVAN speaks of political rupture. Vila31 x Art Explora introduces contemporary public practice. The Tulla Culture Center and the Agimi Art Center contribute distinct cultural textures. Bar Thaka grounds the project in local intimacy. Together they form an urban sequence that reflects Tirana’s layered identity and its constant search for new forms of expression.

Villa AVAN

The first chapter at Villa AVAN turns to Xhanfise Keko and Urani Rumbo, whose work imagined other configurations of the world long before such gestures received proper recognition. Their archives guide the viewer through photographs of film sets, scenes from children’s cinema, and theatrical material drawn from Kinostudio. These elements trace a path where repetition becomes a pedagogical field and autonomy becomes a quiet strategy of emancipation. The political climate later absorbed much of their cultural influence, reshaping it for its own agenda. During their lifetimes, their roles as innovators remained obscured, yet their presence in this exhibition affirms the scope and urgency of their vision.

Figures such as Xhanfise Keko and Urani Rumbo introduce a lineage of cultural labour that shaped Albania’s pedagogical imagination. What drew you to foreground their practices as the opening of this first chapter?

From a curatorial perspective, I approached the cinematic practices of Xhanfise Keko and the theatrical practices of Urani Rrumbo not as historical or documentary materials, but as testimonies of an urgency that remains active in the present. Their work within pedagogy, through and with children and women, theatre, and music, as well as alongside subaltern figures of that period, is not read as a closed chapter of contemporary cultural history, but rather as a point of departure.

Placing them at the beginning of this first chapter meant proposing them as the origin of a genealogy that is neither linear nor celebratory, but one that runs through the project and is reactivated in the practices of contemporary artists. In both cases, my interest lay less in the final form of the works than in their methods: the ways in which cinema and theatre become tools for education, for the collective construction of imaginaries, and for negotiating the tension between autonomy and discipline.

These practices emerge in contexts marked by strong political and social constraints, yet they nevertheless manage to produce spaces of possibility, play, and self-representation. In this sense, Keko and Rrumbo embody a tradition of cultural work that places pedagogy at its center as political territories, capable of activating forms of imagination and self-determination that resonate deeply with the urgencies of the contemporary artists involved in the exhibition.

Driant Zeneli

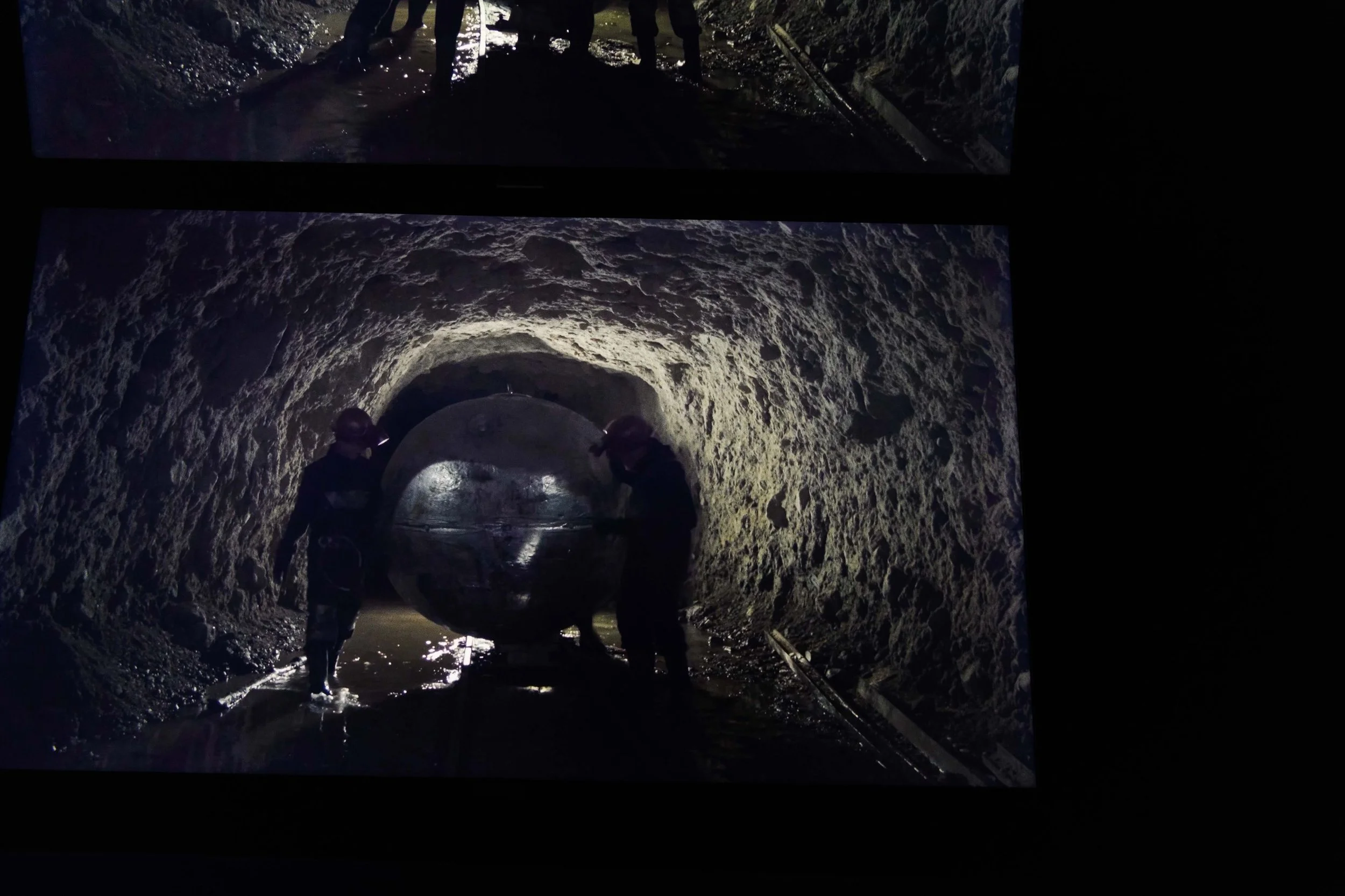

Maybe the Cosmos Is Not So Extraordinary returns in its full form. Teenagers from Bulqizë re-stage an alternate path inside the mine where their families worked, guided by a censored science-fiction story and a found capsule. Through play, they retrace the voyage of chromium and shift an oppressive context into a field shaped by imagination and youthful agency.

Sem Lala

Spitroast Oblast Males presents a set of flagpoles behind glass, emptied of national emblems and charged with a hint of voyeuristic staging. Desire, belonging, and queer references circulate through sound, as the artist echoes his brother’s lessons in English like a loose chain of murmured repetitions.

Genny Petrotta

Novelline revisits Arbëreshë tales documented by Cristina Gentile Mandalà. Four openings of folk stories return through voice, rhythm, and gesture. The video restores fragments of communal transmission shaped by women, labour, and oral memory, turning repetition into a political gesture.

Genc Kadriu

Uncreate revisits the ancient oak oracle of southern Albania. A duplicated leaf and a domestic object acquire ritual weight, echoing the long history of revelations carried by exiled voices and translated signs.

Your curatorial approach treats the fable as a living structure, how did you build a framework that treats the fable as an active force, able to shape collective memory and cultural interpretation today?

AB: In the project Re-enact a Fable, I approach the fable as a haunted form, especially when observed from a diasporic position, where narratives of the past never appear as something closed or complete. Edward Said spoke of having “an extra pair of eyes” within the condition of exile, a way of inhabiting history that never fully coincides with what has been, yet continues to exert an influence on the present. For me, this doubled gaze opens up a particular relationship with myth, with cultural genealogies, and with everything that is transmitted as collective memory within this exhibition project.

When I began conceiving this first project for Tirana, it felt natural to start from this very sense of double distance. The fable and its morphology became a field of active forces, something that continues to generate imaginaries, shape identities, and negotiate forms of belonging. I am thinking, for instance, of the video installation Maybe the Cosmos Is Not So Extraordinary (2019) by Driant Zeneli, or the video Novelline (2025) by Genny Petrotta, where the re-enactment of specific narrative schemes is particularly evident. In Zeneli’s work, this occurs through the re-enactment of Drejt Epsilonit të Eridanit (1983) by Arion Hysenbegas, a book banned during the socialist period, set in the Bulqizë mines, where the performers are the miners’ own relatives. In Petrotta’s, it emerges through the repetition of the opening structure of several fables by Cristina Gentile Mandalà, an Arbëreshë poet from the early twentieth century.

Here the morphology of the fable is questioned through the very logics that govern its narrative structure: a study of forms grounded in repetition, in the recurrence of motifs and functions. If we consider the fable, after all, as a pedagogical device that—through the notion of the double and specific representational strategies—shapes collective imaginaries and conveys a worldview, then repetition appears not as a neutral formal element, but as a structuring principle. This repetition materializes insistently across the works presented. It is present, for instance, in Gentian Doda’s research on the body, developed with Was bleibt kollektiv, where a video sequence is repeated three times, turning the body into a site of durational strain and iterative discipline. It reappears in Anita Mucolli’s puzzles composed of movement “permits,” where repetition mirrors the bureaucratic reproduction of control and restriction. And it surfaces again in Djellza Azemi’s travelling rubber ducks, pierced by a gunshot—objects caught in a loop of displacement and interruption.

Analyzing its architecture means bringing to light its metamorphic nature: the dynamics of transformation, the shifts and mechanisms that allow its constant rewriting over time. In this sense, the works in the exhibition do not illustrate a pre-existing narrative; rather, they use the fable as an operative principle, as a formal system to dismantle and reinsert elsewhere. Through contemporary gestures, images, and devices, the artists make visible the underlying structures that render the fable a living organism with its functions, its unstable roles, its capacity to migrate, to sediment, and to re-emerge in completely different contexts.

To treat the fable as an active force means acknowledging its ability to shape the present while offering a space in which those narratives can be rewritten, contaminated, or overturned. The exhibition is conceived as a site of symbolic renegotiation, where memory and imagination meet from positions that are never entirely stable.

Anita Muçolli

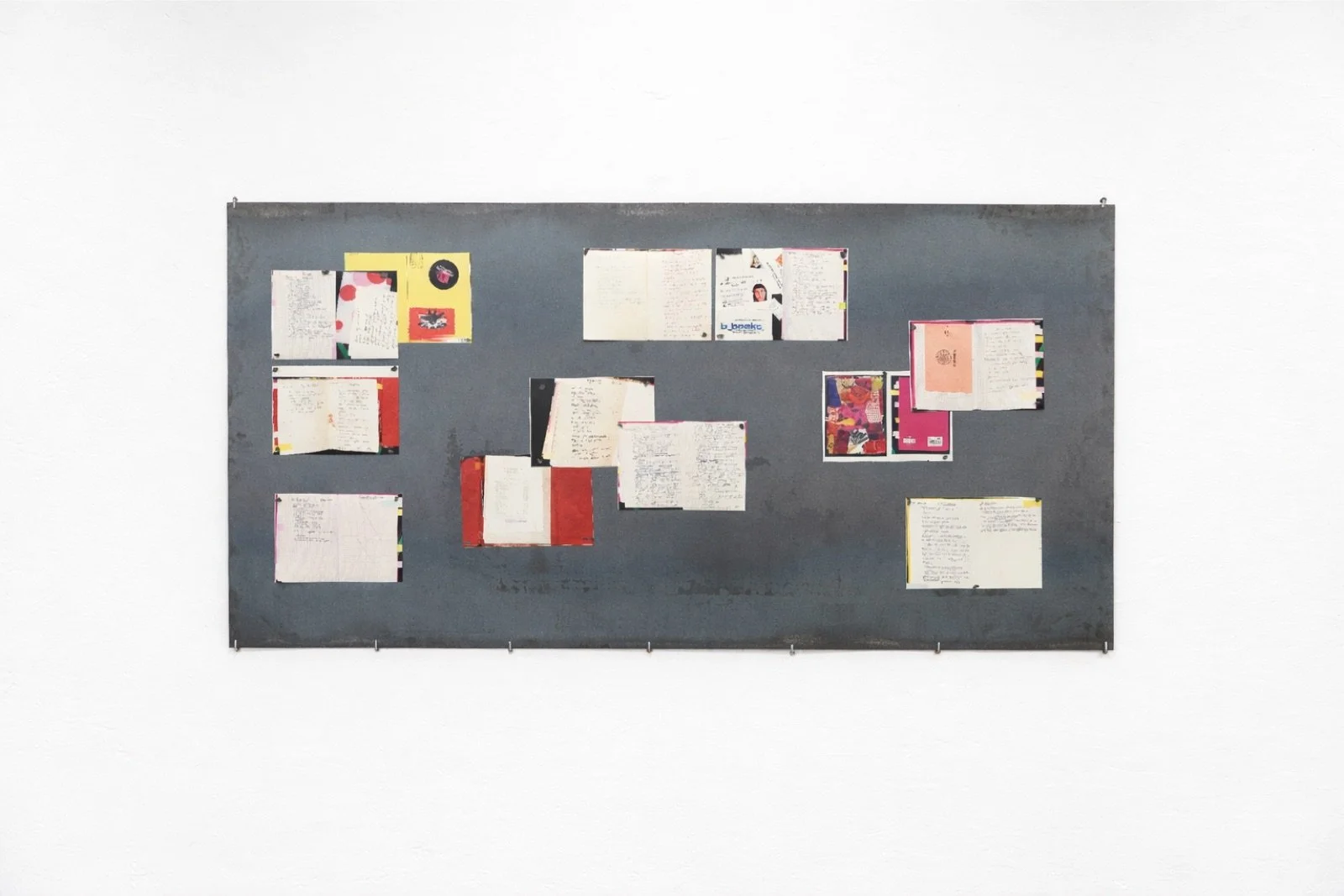

Homelands, Fairylands reconstructs a personal archive through two puzzles built from a voided Yugoslav licence and border stamps from a family journey. Administrative records become pieces of a childhood vision shaped by exile, distance, and the quiet gap between paperwork and lived memory.

The exhibition occupies multiple sites across the city, each with its own weight, history, and political residue. What guided your decision to allow Re-enact a Fable to be across such distinct urban spaces, and how do these locations speak to the project’s wider intentions?

First of all, the idea of conceiving Re-enact a Fable as a curatorial platform in continuous metamorphosis, expanding, shifting, and transforming across the city’s spaces, was already aligned with the theoretical premises of the project, starting from its very title. If the fable is a mobile structure, traversed by variations, rewritings, and duplications, then the exhibition too had to embody this organic logic through its own re-enactment.

The dimension of the double emerges precisely here: each location activates a different version of the exhibition, as if the fable were doubling itself and taking on multiple forms without ever becoming definitive. The “double” is not only a recurring motif in the morphology of the fable, but also a way of imagining the exhibition as something that always exists at least twice, in its physical configuration and in its potential one.

Situating the exhibition across different urban sites therefore meant allowing the narrative to open onto multiple thresholds. Each space with its own history, political weight, and degree of transformation functions as a “chapter” of a story that is not read linearly but through crossings, returns, and deviations. The exhibition offers neither a single beginning nor a definitive conclusion.

This choice reflects, in my opinion, a form that extends and transforms itself, much like the urban spaces of Tirana, which are likewise engaged in a continuous process of stratification, erasure, and reappearance. Bringing the exhibition into the city meant acknowledging that its metamorphoses are not merely a curatorial device, but a real, almost ontological condition of the place in which the project takes shape.

Anna Ehrenstein

A curtain introduces a fracture in the corridor, altering orientation and perception. The sentence “Home is where the hatred is” anchors a reflection on belonging, control, and the hard failure of domestic refuge.

Villa AVAN carries a history marked by trauma, resilience, and bureaucratic violence. How did you negotiate the presence of this building as a host for works that address autonomy, childhood, censorship, and self-determination?

The Institute for the Integration of Former Political Victims / Villa AVAN as you anticipated is a site marked by an extremely stratified history and shaped by trauma, bureaucratic violence, and the suspension of individual rights. For this reason, rather than “occupying” the space, the curatorial approach began from the necessity of negotiating its presence, avoiding any form of spectacularization or rhetorical overlay of pain.

The project does not address repression in a frontal or illustrative way, it consistently works through lines of escape: through the methods by which subaltern subjectivities have constructed spaces of autonomy within or at the margins of oppressive systems. In this sense, the decision to begin with figures such as Xhanfise Keko and Urani Rrumbo was central. Pedagogical work with children, as well as theatre and music practices developed by women in southern Albania at the beginning of the twentieth century, are here read as concrete dispositifs of self-organization and self-determination.

Subalternity runs throughout the entire project, but not as a condition of passivity. On the contrary, it becomes a privileged vantage point from which to focus on unofficial modes of knowledge transmission and on forms of community-building that exist outside the languages of power. In this context, childhood, the body, the voice, and the theatrical gesture emerge as political territories, capable of temporarily eluding mechanisms of control and censorship.

Presenting these works within the former Institute for political prisoners of the communist regime is not resolving the trauma of the site, but placing it in relation to histories of autonomy that traverse its cracks. Villa AVAN thus becomes not only a container of memory, but a critical space.

Renid Tosuni

Through painting, collected plants, and glass, Tosuni traces a southern landscape held between memory and observation. Unpacking and This time I did not light a candle turn touch, fragility, and interruption into a small archive of place.

Tirana sits at the center of rapid transformation. How did the city itself influence your curatorial decisions, especially in relation to the works shown at Thaka Bar and the Agimi Art Center?

From the outset, the project was conceived as a collaboration with multiple spaces and realities across the city, understanding each of them as a fragment of a broader platform, or as an autonomous platform in its own right. This distributed articulation made it possible to engage with Tirana not as a unified context, but as a constellation of heterogeneous situations, histories, and temporalities.

At Tulla Culture Center, we presented Blerta Haziraj’s work on the antifascist women’s movement in Kosovo in the postwar period, a series of musical instruments from a small orchestra by Enxhi Mehmeti rendered completely dysfunctional, and Silvi Naci’s video focusing on the movement of hands in women’s labor. In this case, the focus was on forms of work, care, and collective organization that are often marginalized, read through the body, sound, and gesture. Meanwhile at the Agimi Art Center, the space was instead activated through a screening program centered on the theme of the fairy tale, as well as on labor itself: as in the case of Doruntina Kastrati’s film, which addresses the conditions of workers involved in the construction of the city of Prishtina and the forms of structural precarity that permeate these processes. Here, the narrative and symbolic dimension of the fairy tale intersected with a material reflection on labor and urban infrastructures.

At Thaka Bar, finally, together with Gerta Xhaferaj, we sought to draw attention to the culture of Tirana and to a space of sociality that has remained relatively authentic, not fully absorbed by the logics of branding and the city’s accelerated transformation. The idea was to understand these places as genuine activators of culture in a city undergoing rapid change, presenting them as true “centers” of cultural production, both official and unofficial.

Gerta Xhaferaj

The Censorship of Flowers exposes ruptures in family footage. Floral inserts highlight the intervention of the father’s overwritings and reveal how domestic archives carry omissions, violence, and rewritings beneath their surface.

Djellza Azemi

untitled (backyard solitude) presents five punctured rubber ducks, drawn from a childhood image. They stand as small travellers marked by the disquiet of displacement and the unfinished paths of the diaspora.

It was fascinating to see how the shared choice to install Gerta Xhaferaj’s work inside Thaka, a bar with deep local character and social memory, paid off. That decision cultivated an atmosphere of genuine proximity, particularly during the live performance. How did you envision the relationship between her piece and the everyday life of that space?

Gerta Xhaferaj had wanted to activate this space for a long time, and the idea emerged in a completely spontaneous way, while drinking raki and eating qofte on the bar’s rooftop. Within a project that defines itself as Tirana Art Week and that also engaged an international audience, we thought it was important to bring them into contact with a space like this, one deeply rooted in the city’s everyday life. This was also made possible through the performances by zerocase & nica2cica and Sindi Ziu, who introduced sounds of the city and a DJ set marked by incursions of Balkan underground music. We did not want to impose ourselves on the space: we simply asked to use the screen that is normally used to broadcast football matches, and we worked with the same tables and the same blue-and-white tablecloths already present in the bar.

In this way, the work was able to integrate naturally into its context, without interrupting or artificially redefining the everyday rhythms of the place.

Sonja Azizaj

A large panel gathers poems written during Tirana’s rapid shifts. The text forms a counter-map through which the city’s instability gains a voice.

The exhibition points toward a new way of reading archives, gestures, and personal histories. What do you hope audiences carry with them after moving through these spaces, and how do you imagine the fable continuing to act beyond the exhibition?

First of all, I hope that what remains is a sense of the density of Tirana’s art scene and its multiple masks. A deeply stratified scene, traversed by very different languages, positions, practices, and perspectives. Tirana emerges as a constantly shifting field of forces, where artistic practices take on different forms depending on the contexts, roles, and relations they activate. Within this complex ecosystem, it is also important to acknowledge the work carried out by certain institutional presences that have long contributed in meaningful ways to sustaining and making this density visible, as in the case of AVAN.

Secondly, the project advances a reflection on archival work and on how history is constructed. We have learned that history is a modernist, hierarchical, and vertical construction. Paraphrasing Foucault, it is therefore not a matter of accepting the ensembles that history presents to us, except in order to immediately put them into question. In this sense, the work with archives sought to produce a displacement, to unsettle dominant genealogies and to “liberate” certain historical figures from the socialist specter that continues to determine their reading.

I hope that rather than offering a closed alternative narrative, the exhibition opens up a critical space in which archives, gestures, and histories can be reread as unstable, unfinished, capable of generating new connections and new imaginaries in the present. The center of the world is not a stable place, but something that can emerge anywhere. There is no definitive center, nor a single history from which everything originates. The center is produced each time, through situated practices, relations, and acts of rereading. It is in this possibility of continuously shifting the center of the world that archives, local scenes, and histories become active sites of imagination and political action.

Thaka Bar

The closing chapter develop inside Thaka Bar, one of the few historic places that still stands in the rapidly changing Blloku. Here, Gerta Xhaferaj proposes a site-specific intervention. A video installation occupies the ground floor screen, usually reserved for football matches, and gently enters the daily rhythm of the bar’s regulars. The upper floor hosts a projection and a live sound performance by zerocase & nica2cica and Sindi Ziu, invited by Gerta Xhaferaj.

Tulla Culture Center

Here, gesture becomes a way to confront history. Blerta Haziraj focuses on the Women’s Antifascist Front of Kosovo, revealing a near-erased female lineage through videos, photographs, and archival fragments.

Collective writing appears as a vital gesture that persists across time, turning the archive into a space where disorder becomes a possible form of repair. Enxhi Mehmeti introduces altered musical instruments, stripped and rebuilt into unstable forms that echo children’s toys. Together they form a dissonant orchestra. Silvi Naçi presents Actions That Make My Hands Hurt, a film built from action verbs tied to labour, care, domination, and rupture. Gesture emerges as a political terrain where every movement carries the weight of power.

Agimi Art Center

This chapter of the exhibition gathers a collective screening focused on workers and the stories carried through their labour. The selected films study work through material, political, and emotional angles, tracing how its weight marks bodies, gestures, and private realities. Documentary methods, performative choices, and forms of fabulation sit together, each revealing what labour produces and what it leaves outside the frame. Tensions, absences, rituals, and quiet forms of resistance surface through these images. The program includes films by Blerta Haziraj, Genny Petrotta, Xhanfise Keko, and Doruntina Kastrati.

Vila31 x Art Explora

Within Vila 31 x Art Explora, Erdiola Kanda Mustafaj presents Fry, të frysh, frymë, a reconstruction of a familial purification ritual passed down through subtle repetition. The grandmother’s incantation combines Albanian with Turkic-Arabic fragments, creating an archive with rhythm and breath. The video is built on two gestures shaped by water and fire. In the second, the artist drives the ritual backward in time, attempting to light fire on water as a reference to the gas emerging from the seabed.

Bazament

In Whispers under the Relentless March, Blerta Hoçia presents three video works and a public intervention exploring how lives and landscapes absorb the weight of political transition. Set in her childhood neighborhood in Tirana, the exhibition reveals the erosion of intimacy and community under the guise of progress.

State of Condition (2025): A cinematic exploration of Tirana’s neighborhood soundscapes. It contrasts intimate community "coffee pockets" with an erratic modern pace where private profit increasingly dominates collective needs.

Solidariteti (2025): Titled after Albania’s first call center union, this film examines the youth-dominated industry. Filmed during COVID-19, it highlights the alienation and surveillance that turn the home into a workspace.

Fho Fragments (2025): Juxtaposes the natural flow of a river with the deafening, repetitive noise of political rallies and broken promises, illustrating a cycle of stagnation despite the "commotion" of change.

Tirana Art Weekend

Curated by ARNOLD BRAHO

Words and interview with Arnold Braho by DONALD GJOKA

What to read next