ARI ASTER: The Unbearable Accuracy of the Millennial Thread

Ari Aster belongs to that cluster of Millennial cycle-breaker directors who inevitably find themselves unraveling issues central to their generation, bringing to light dynamics that, while universal, are experienced by each generation with specific nuances.

In his first three feature films, he has explored the fears and echoes of trauma that most people born around the digital revolution have begun to confront more consciously than previous generations. If these can be seen as a sort of trilogy on family trauma, his latest work, “Eddington”, shifts the focus on a collective level, keeping the same knots tightly bound, but zooming out to reveal the whole web we’re in.

So, starting from the personal dissection of the relational microcosm, we’ll try to understand what Ari Aster carries over into the telling of the systemic macrocosm throughout his filmography (spoilers ahead), since identifying and fighting against traumatic patterns and toxic behaviors with a certain degree of accuracy is something that, as the cycle-breaking generation, Millennials basically invented, as we all know.

Millennials were the first generation to have the opportunity to develop a broader understanding of systemic trauma and intimate power dynamics, thanks in part to digital tools that have enriched the ways we share our stories and build a sense of a broader community as a new, chosen, and expanded family.

This is a concept that deeply resonates with Aster’s storytelling: completely different stories and relationships are bound by a fil rouge stretched to its limit, in constant tension, an invisible yet razor-sharp line between the characters.

And it is precisely the impossibility of cutting those threads, of killing the bond, symbolically or otherwise, that generates the unbearable. The very meaning of “family,” as it has been taught to us, is the real horror here.

In each of Aster’s films, there seems to be a form of catharsis from a state of grief and solitude, sometimes finding an anchor in a hive-minded community, and at other times succumbing to the abyss.

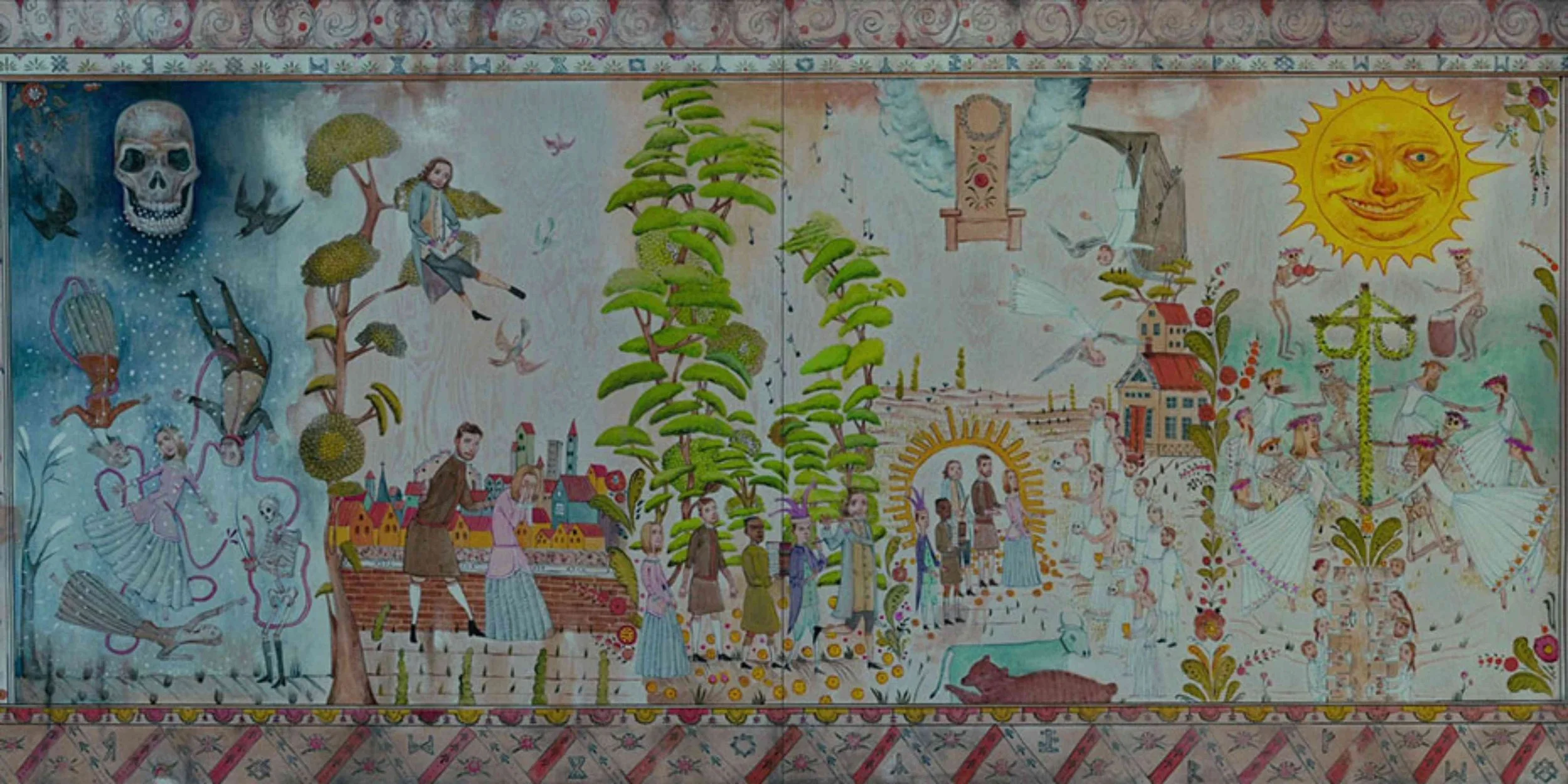

Recurring symbols act as a thread across the first three films, each fitting into a broader, generational narrative with its own specific shape and function.

The house becomes a stage, a container for rituals and catharsis, its dimensions mirroring the relationships that intertwine within it and the intimate space of those who inhabit it.

Dioramas, treehouses, rooms for death and trauma, of cuddles and abuse, these houses are spaces that contain both social and intimate interferences.

Domestic spaces and characters intertwine with the natural environment, which envelops or frames them, as if to represent a condition that transcends the boundaries of individual families and becomes an intrinsic discourse about human existence itself.

The role of Nature is both symbolic and factual, an ancient engine that turns up in an archetypal distant place and then crashes into reality with a catalytic propulsion.

Beyond the environment, the natural elements are crucial for character development or annihilation, shifting from the first fire-centered dynamics to a water-dominated paralysis.

Between these artificial and natural spaces stand the people, their bodies, their actions.

Manipulative relationships are the glue that keeps the director’s stories together, those based on emotional blackmail and a sense of sacrifice injected as the only antidote to pain, the only currency for love and forgiveness from those who should love you unconditionally.

The redundancy of behaviors passed down through generations is echoed through the repetition of sounds: knuckles on a door, voice tics, ritual vocalizations.

The head is a hysterical cradle, destined to be erased, crushed, pierced, dissected. By its absence, we can feel that both subject and object are always somewhere else, displaced, projected, and distorted.

HEREDITARY: The self fractured by grief

Inheritance is clearly the core of Ari Aster’s first feature, the key concept that opens an unofficial trilogy exploring family-grief-drama and intergenerational trauma.

“Hereditary” opens with a funeral party and a camera movement that shifts from the real house into the dollhouse: from the very beginning, the viewer is immersed in a narrative suspended between the domestic and the symbolic, between family life and ritual dimension.

Rituals are central to the women portrayed in this film as behaviors inherited from a malevolent seed and from a manipulative and power-driven woman, but which, as they pass to later generations, shed their original intent, shifting from catabolic-only to a whole metabolic ritual, taking on the contours of a therapeutic process.

The dollhouses built by the protagonist faithfully reproduce her family’s condition: a set constructed so that the fabric (or wooden) figures can be moved by an external power, a greater, intrinsic, inescapable one.

Annie uses this symbolism to become the hand that moves and rearranges, to regain control over the traumatic events of her life: to observe them, reconstruct them with meaning, reshape them according to her own narrative.

Indeed, the various dioramas depict real scenes from her past, places to revisit for re-elaboration or to keep sealed as reminders and omens.

The guilt generated by trauma is the hereditary demon, a seed that triggers a series of catastrophes, just as the walnut triggers the demonic plan.

Domestic sounds become omens of death: the knife on the cutting board, the knocking on the door, and later the mother’s head knocking against the attic door and the son’s head against the desk.

So, as the wood, the house and the trees are one unique organism growing from generations, from the roots to the crown, from the feet to the head.

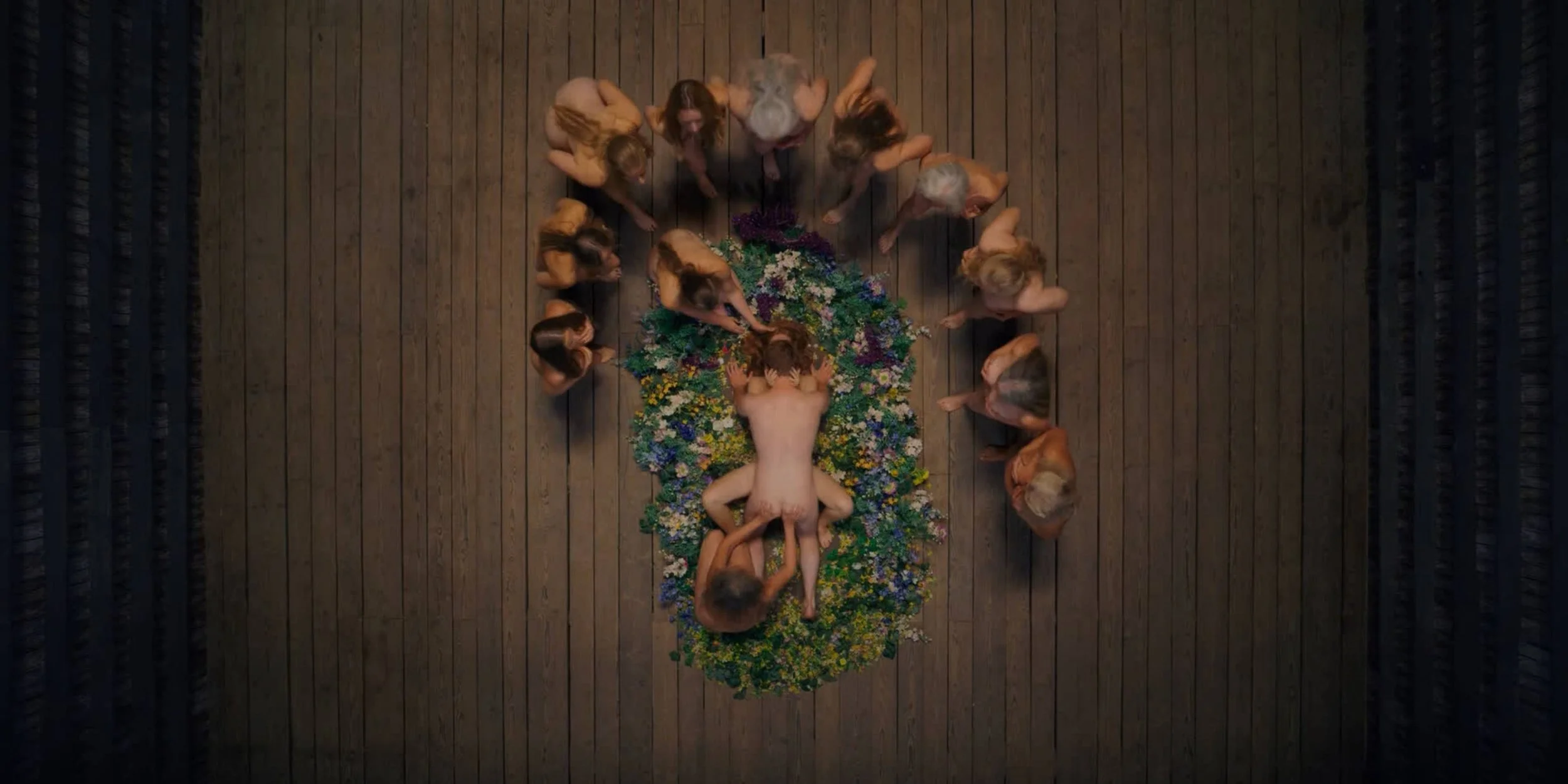

MIDSOMMAR: The self dissolved within the collective

“Midsommar” is itself a celebration of womanhood and female power, as the Northern festivity near the date of the summer, this is deeply tied to the pilgrimage towards adulthood and the empowering process needed to build safe romantic relationships.

Dani stands at the midpoint of her adult journey, trying to understand who she wants to become, where she belongs, and above all, with whom. Symbolically, she moves away from her family and trauma, trying to build her chosen one

She has no emotional support, yet feels responsible for others; she wants to be considerate and accountable, setting her own needs aside. A shy need for understanding and connection, while the world around seems to make her feel even more lonely: missed calls, emotions left unacknowledged, and that email inbox at the very beginning of the movie, an academic newsletter saying: “Are you networking? You should be!”

As meeptop points out in his video essay on YouTube Dani is an echoist: a concept born from the character of Echo, the woman condemned to love Narcissus and speaking only the last words others pronounce, and brought into literature by Donna Savery as a mechanism that serves as the psychological counterpart to narcissism.

Dani is preserving her relationship from her real emotions, doing everything possible to please her Narcissus so she won’t be left alone.

The first time she truly smiles is when she enters the commune for the first time, and at the end, when everything from her old life is gone. All the rest was just masking.

Through the rituals of love, initially incomprehensible to her, she reclaims her own capacity for love, learns a new way of perceiving affection, and finally sees her relationship for what it truly is.

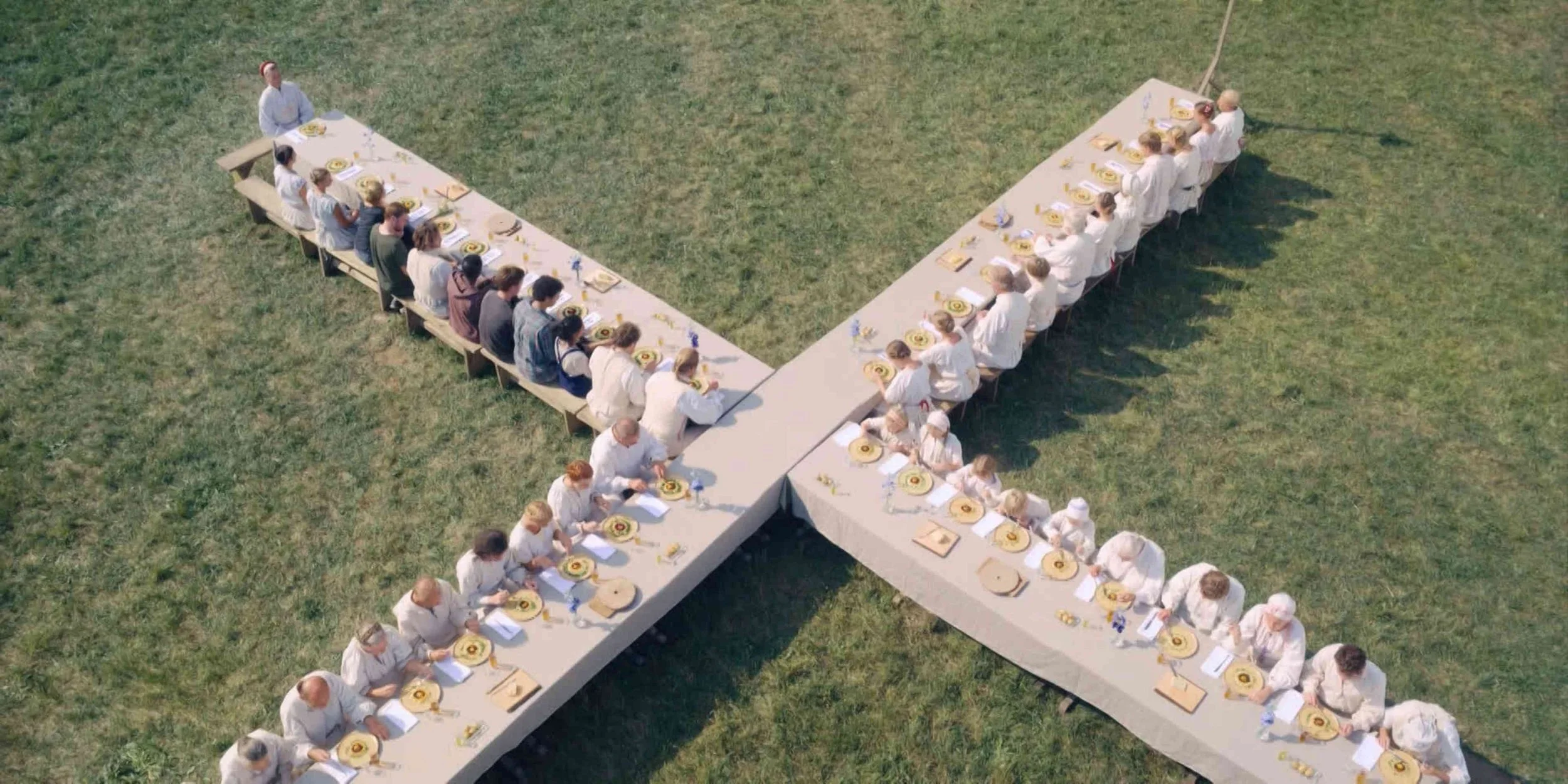

The collective performativity of the acts, aimed at a magical purpose, creates a hive mind.

Empathy is a ritual amplifier, the synchronized expression of pain and the love language of this community, something Dani had always lacked, along with the feeling of being held.

Dani’s scream of pain at the beginning is muted in Christian’s passive embrace, as the darkness and the snow don’t allow her pain to be delayed and be liberated.

At Hårga, we see a completely different scenario, all the horrors can be exposed to light, exorcized, and be sublimated and liberated through collectivity and ancestral, intentional, vocal and breath affirmations.

The concept of house in this scenario is decentralized too; we see different locations that serve as sites of specific rituals and sacrifices, dorms with multiple beds, and one big family table.

Being one with the people also means being one with the environment.

Hallucinating to be absorbed into nature is a cathartic, psychomagical death, Dani becomes part of the whole, as her sister did, and is finally ready to accept death.

In the same way Dorothy Gale in The Wizard of Oz accepts her own power and finds, in some way, a new idea of what home should feel like.

BEAU IS AFRAID: The “I” trapped in guilt and reiteration

Beau’s story is told through his own voice, that of the so-called unreliable narrator, since what we witness is a slow descent into his own abyss, saturated with symbolism and projections, with endless repetitions of “thank you” and “sorry,” uttered like a prayer.

The core of the protagonist’s unresolved pain lies in his relationship with the maternal, and the way it has shaped everything related to the interpenetration of the masculine and the feminine. It’s a dynamic ruled by guilt, that kind of guilt that comes from so many directions that it paralyzes him; the longing to disappear and find peace, the fear of not being enough, of doing the wrong thing, of failing to live up to masculine standards.

The feeling is so vivid that it blurs the boundaries between reality and psychosis, leading him to believe that everything is a staged trap designed to expose him before a judging audience, as indeed a horrible and insignificant person.

Thus, all the typical fears tied to a child’s performance in relation to a parent, whether born from real acts or from projections echoing from the past, turn into a spiral of annihilation and self-punishment.

He will never be enough, not for her, but for his perception of her expectations.

When he wants to do an act of care and love by buying her a little statue portraying a mother holding her baby, he eventually finds out that at her place she already has the same monolithic totem in her beautiful garden, but of course so big that his gesture becomes insignificant.

Their houses are the actual spaces they live in Beau’s mind, the mirror of his perception of himself and others: Beau’s place feels little, uncomfortable, threatening and messy, while Mona’s is a wide wooden womb, in which every step is a threshold to a memory, there are no doors to open or to be closed.

Mona Wasserman represents not just the typical mommy issues dynamic, but the castrating mother archetype in a perfect mother-horror depiction. The invisible hand that guides every step since your first ones, shaping every relationship and reaction.

In this genre, monstrosity doesn’t have to be intentional; unintentionality creates the real terror and tension, because it leads to the hypothesis of being guilty, selfish, hurting, and disappointing. Mona is a mother who infiltrates through every crack, in which creation she partly participated.

“It wasn't a dream, it was a memory!” she shouts to point out that we are entangled in Beau’s synapses, with the growing sensation of approaching a traumatic knot, while the lines between dream and memory, external and internal voice, become increasingly confused.

We have a hint of this curse since the first scene of Beau’s birth, since, as Erin Harrington writes about the Gynaehorror concept, “the woman-as-subject and the foetus-as-subject do not happily coexist or conjoin; instead, they struggle for dominance”.

Beau is destined to fail this fight. When he tries to suffocate her voice to reaffirm his individuality, he’s punished with her performed death, with the final “look what you’ve done”.

He can’t even defend himself; his defense voice, as we can hear in the final scene, is lower than the one who is accusing him, which is the result of the panopticon which has his mother’s eyes.

Her dominance is so present that becomes a fictional voice Beau created in his own mind, reverberating from his cavernous subconscious, filled with amniotic waters, in which drowning is eventually the only way to make the voice stop, totally reuniting with his mother, giving up to her constant horrifying presence and finally getting home, but in a different way, drowning in that water that can be a symbol of care, life, motherhood but also danger and death.

EDDINGTON: From the intimate to the systemic

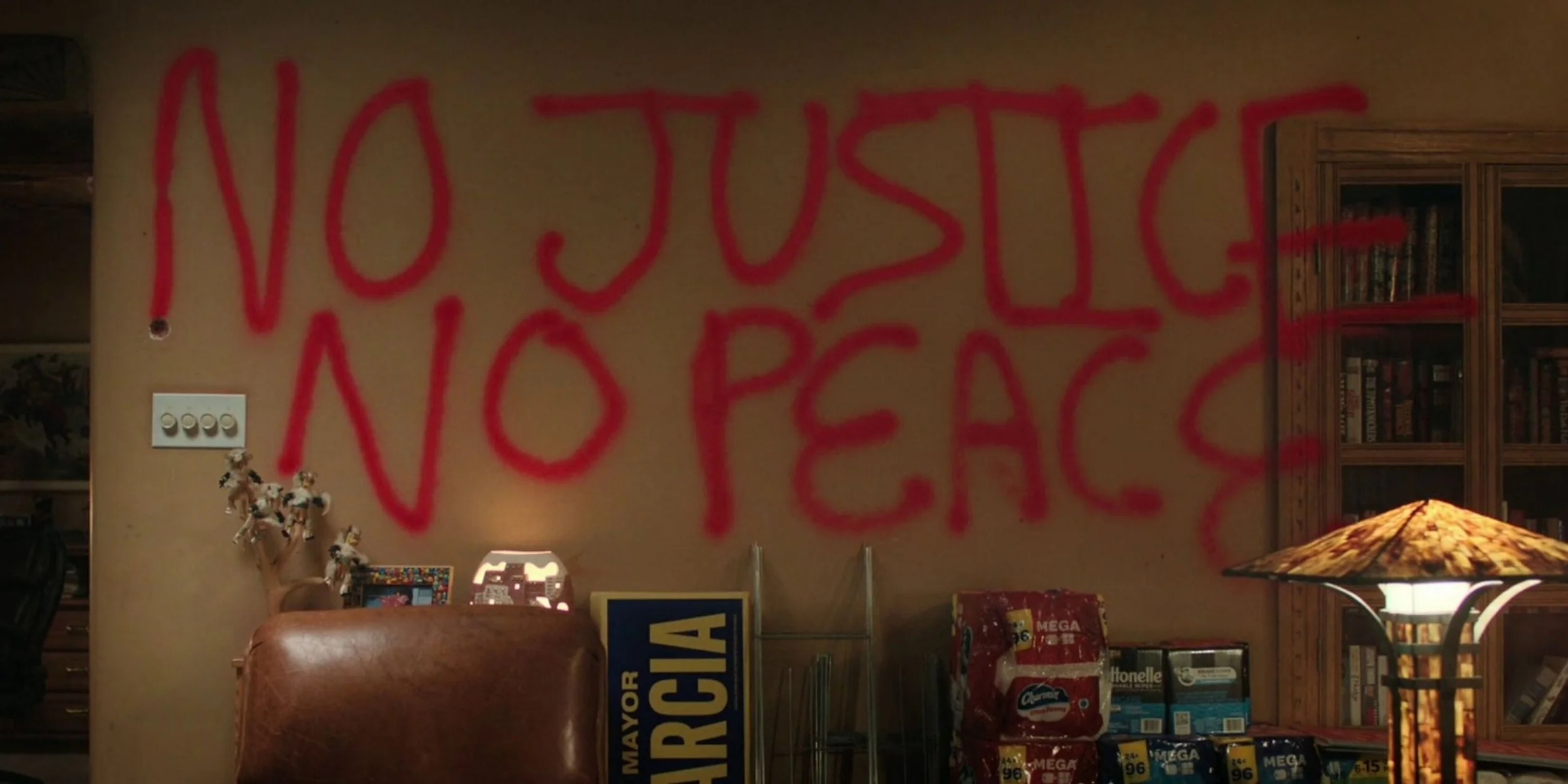

If the first three films can be seen as a trilogy of inherited and internalized trauma, “Eddington” marks a shift in scale: from the anatomy of a wound to the cartography of a network. Aster’s gaze moves outward, yet the threads remain the same: the bonds that cannot be cut off, only expanded, refracted, multiplied.

The conversation shifts on a wider level, as he tries to depict the scenario in which all our generational traumas, conflicts and inadequacies are exposed and the performative masking falls off with the sound of the comic un-relief.

At an intimate level, “Hereditary”, “Midsommar”, and “Beau Is Afraid” stage the collapse of the self under the weight of grief and guilt.

In this chapter, the fracture no longer originates within the psyche, but from the web surrounding us, both the one sewn with our storylines and the one we communicate through.

The trauma of the Millennial self is still “where do I end?”, but on a different scale: the horror of the bloodline becomes the horror of the social fabric, the notion of family finally expands to encompass society itself. It becomes a macro-family governed by invisible expectations, cultural scripts, and the quiet violence of conformity and stillness.

So what can we do with it? Are we really willing to deconstruct it, or is the seed still too deep to be uprooted yet?

Aster himself seems skeptical about this possibility, or perhaps his films embody precisely the failure of any true deconstruction of trauma.

In interviews, the director has described this last movie as a dark satirical Western that examines how people living in different realities are unreachable to each other, reflecting the fragmented nature of modern society and, despite the hyper-connection online, they’re just reiterating their bubbles’ narratives, as his previous characters reiterate their self-narratives.

This might explain the choice of the movie’s name, inspired probably by Sir Arthur Eddington, a British astrophysicist known for his pivotal role in confirming Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity and how the bending of light impacts the nature of reality, and the interplay between perception and truth.

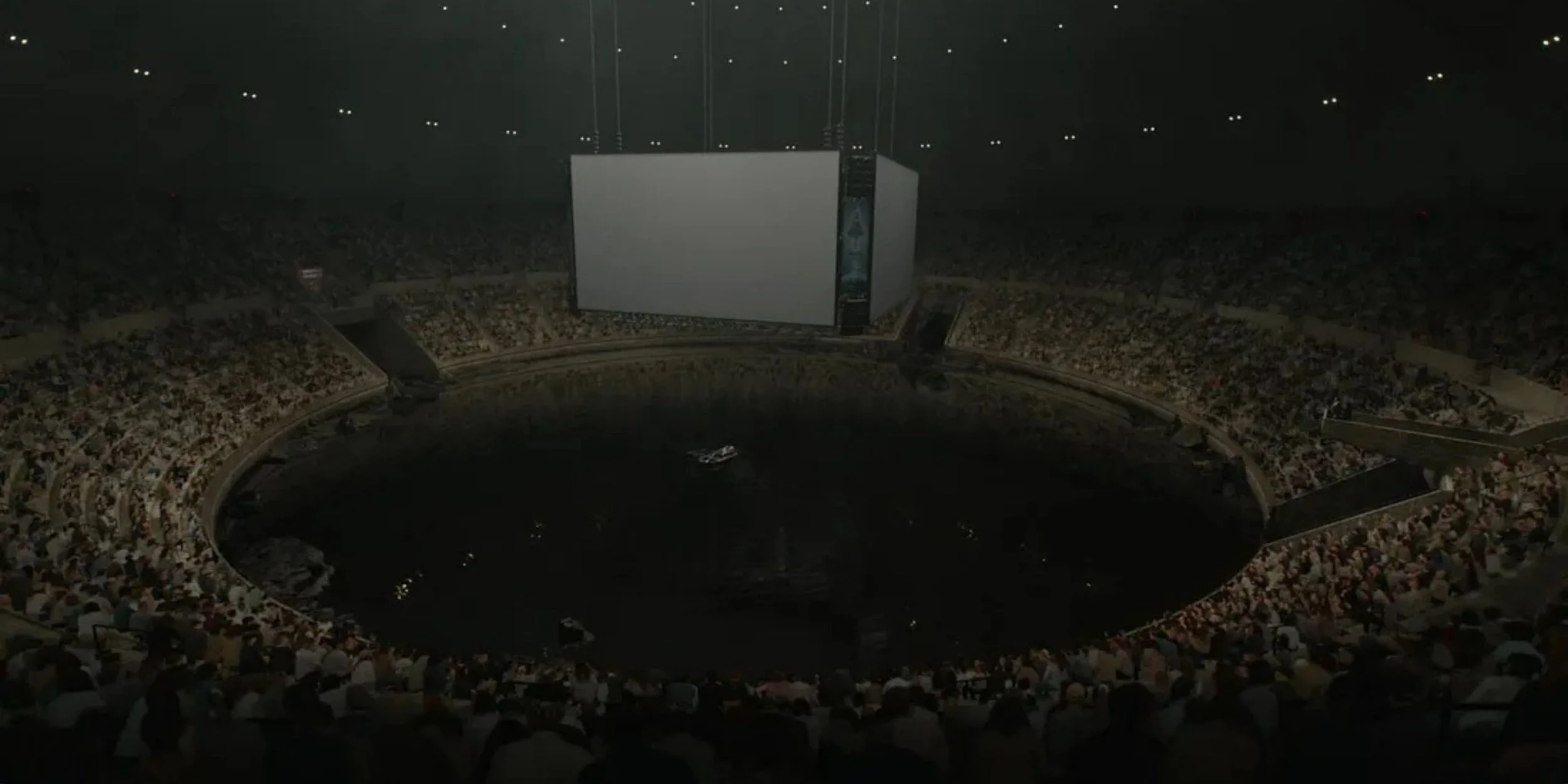

While each of the early films portrays the impossible search for belonging, “Eddington” seems to complete this trajectory: the cult is no longer an aberration; it is the system.

The world itself becomes a ritual, endlessly reenacting our need to belong and our fear (and still, desire) of being absorbed.

Aster shows us with ironic lucidity how our collective perception is warped by the invisible weight of social and cultural bonds, while the moist soil of all the individual yet collective traumas still lies and moves underneath.

Director Ari Aster

Year 2018 - 2025

Director of photography Pawel Pogorzelski, Darius Khondji

Cast Toni Collette,Gabriel Byrne, Florence Pugh, Will Poulter, Joaquin Phoenix, Patti LuPone, Pedro Pascal

Stills and words by LAYLLA ABUGHARBIEH

What to read next