Julieta Tarraubella

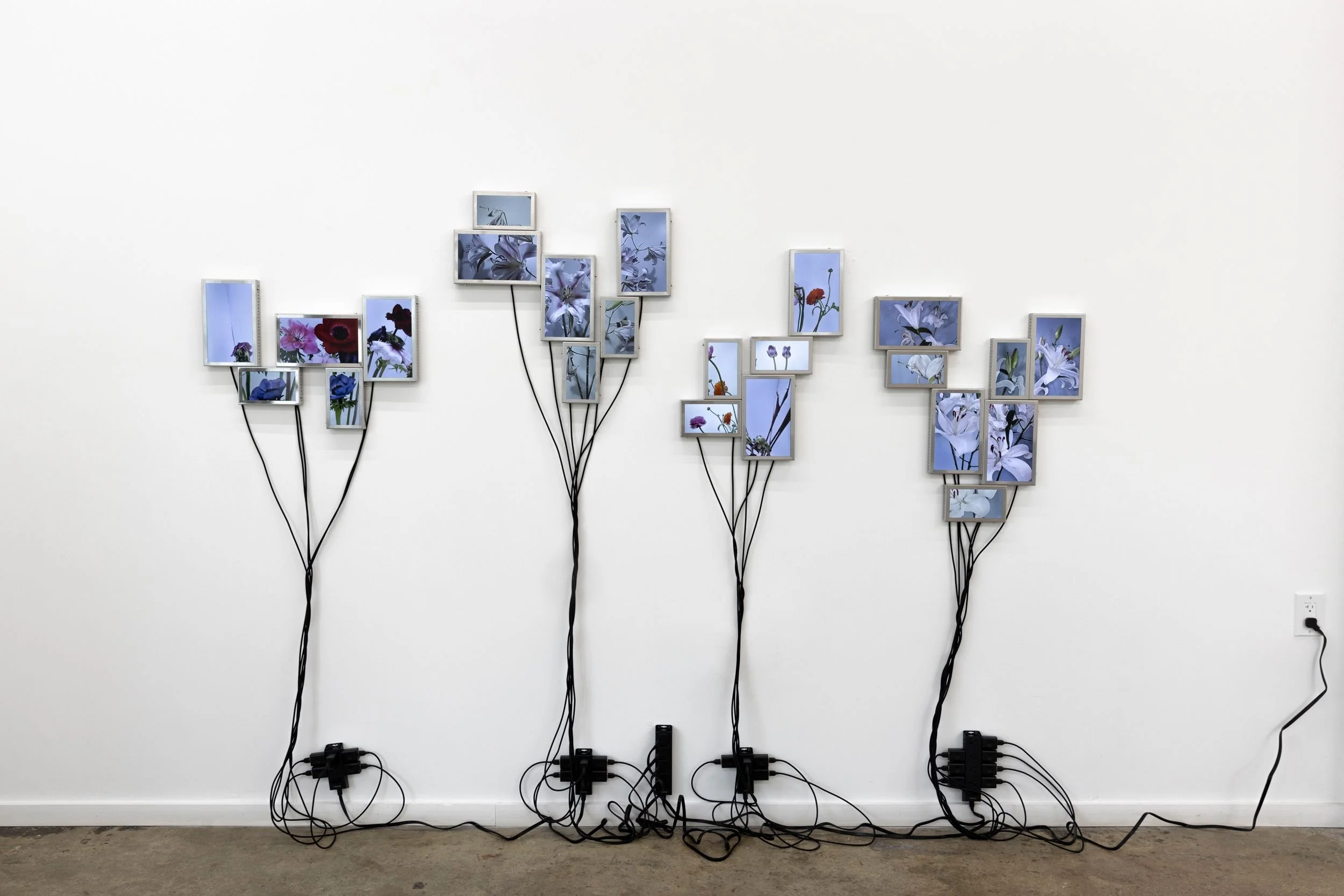

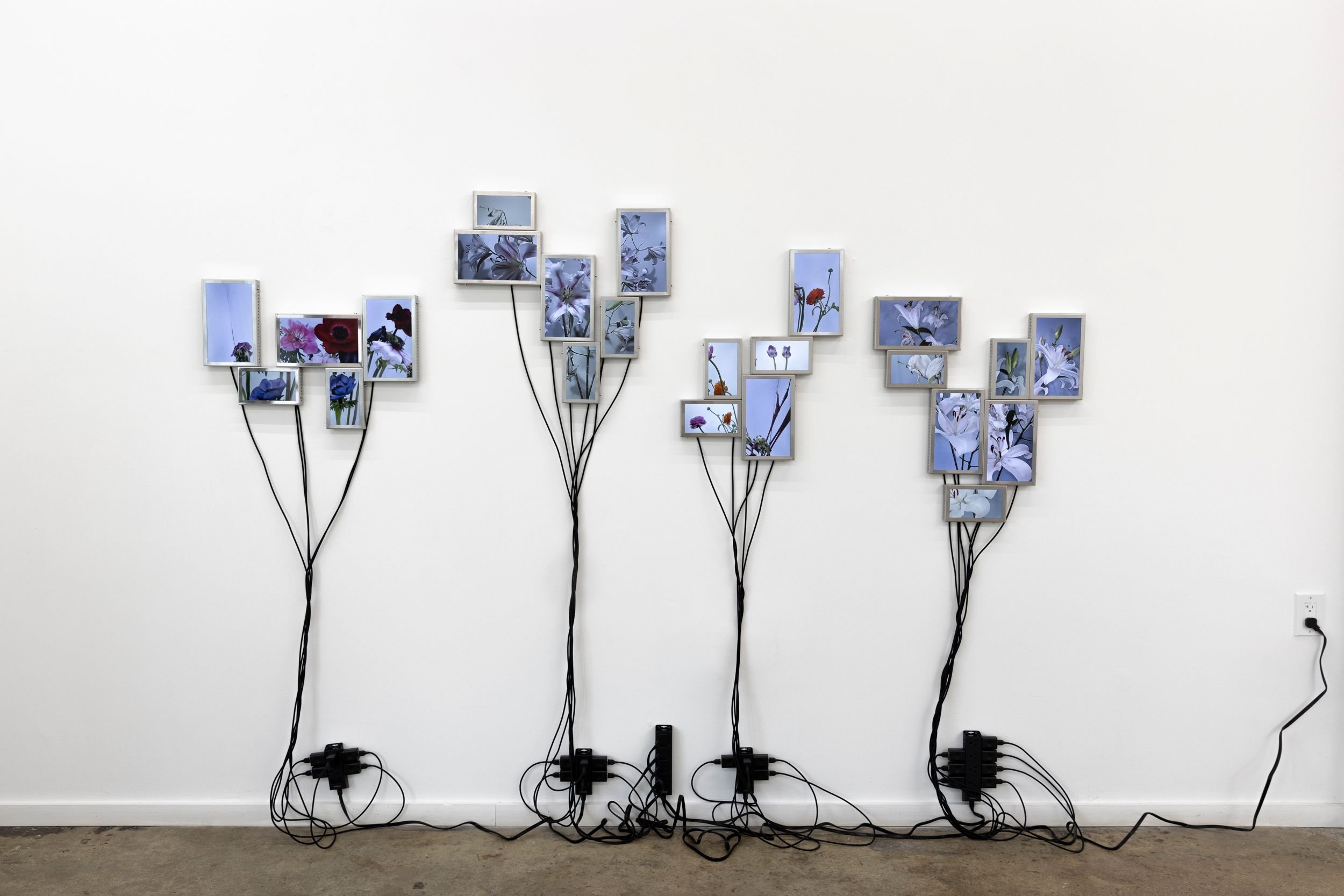

The secret life of flowers, 2025. Exhibition view at Tomas Redrado Art. Photo, Evelyn Sosa.

Julieta Tarraubella’s practice is about duration, attention, and restraint. By following a flower across its entire life cycle, she commits to time as a material. Growth, pause, and decay gain visibility through patience rather than urgency. In a culture defined by acceleration, her work insists on waiting. The flower exists within an exposed technological structure. Cameras, cables, lenses, and screens remain visible, forming an artificial ecology that sustains life. Electricity replaces sunlight as a vital condition. Technology appears neither hidden nor decorative. It stands as a necessary presence, intimate and imposing at once.

Her choice of flowers proves central. Their silence and fragility allow surveillance to reveal its full weight. Observation becomes pressure. Care turns inseparable from control. Viewers often encounter admiration followed by discomfort, a reaction that mirrors contemporary habits of constant recording and monitoring. Long-duration observation reshapes perception. Subtle changes become significant. Decay arrives gradually. Tarraubella watches remotely, often through a phone screen, anticipating transformation or collapse. Distance intensifies responsibility rather than reducing it. Attention sharpens as loss approaches.

The secret life of flowers, 2024. Exhibition view at Art Basel Miami’24.

Your decision to follow a flower through its entire life cycle creates a rare sense of patience in a world that moves at a relentless pace. What first convinced you that this slow temporal arc could reveal something essential about perception and care?

There is something beautiful in the idea of manipulating time, kind of a superpower that I think all of us want to possess, even more now that we are immersed in this “world that moves at a relentless pace” as you say. I feel that in that tiredness of acceleration, there is a need to occasionally slow down to truly perceive and enjoy the present, but most of all to acknowledge and value the otherness that appears against our uninterrupted fast individuality. That is why I believe that showing the arc of life of a living being allows us to connect a little bit with care, something very subtle, that wonders, appears there.

The plant in your work lives inside a technological structure that guides, records, and surrounds it. How do you interpret this coexistence, and what qualities did you want viewers to sense through it?

I am always interested in the clash of tenderness and cruelty, spirituality and raw reality; my work wonders about those encounters in terms of materialities and themes. The flowers in these pieces are perpetually born and die inside these structures, their fragile life depends on the screens, cables, electricity, and on the metal that contains them all – they serve as a tool for immortality. I chose to work with flowers because I wanted to see the invisible action that the sight of cameras has on our bodies and our behaviour, for this experiment I couldn’t work with humans or animals, and flowers appear as the perfect subtle beautiful subject to be subjected to this violent experiment. When viewers meet the works, I want them to feel that unsettling encounter that as humans we experience every day. Sometimes these pieces are looked at with admiration, but sometimes they are perceived with a lot of discomfort, and I am quite happy when that happens as I feel that they activate some kind of self-awareness.

Surveillance Station, 2024. Video installation. Closed-circuit system of 4 security cameras and 4 square-format CRT video monitors. Installation view at Art Basel Miami’24.

Cables, lenses, circuits, and screens sit openly next to the living flower. What led you to present technology without disguise, and how do you see this clarity influencing the viewer’s relation to the plant?

Technology is as natural as nature itself, and it is also very humane. I hate that tendency of hiding it and the intention of denying it. I prefer to embrace it and accept that it is an inherent part of us. A plant possesses roots, and it is fed by light and water, if I am building flowers whose life is possible by the mediation of technology why would I hide their whole apparatus and their need for electricity to live. I am not going to deny their bodies and their humanity, I guess that is the influence I want to generate: a kind of acceptance towards “nature”.

[Detail] Surveillance Station, 2024. Video installation.

Long-duration observation demands a different discipline. How has this project shifted your way of looking at natural growth, and what did this slower rhythm teach you during its creation?

Patience, haha, something that of course I lack. The process of each one of these pieces is quite long. I guess that these experiences made me accept different rhythms. I usually watch them die in the app on my phone, every day I am expecting them to change, to decay in the most radical way so I can later highlight those moments repeatedly. I always liked nature, but let’s be honest I am from Microcentro, the centre of Buenos Aires, I have always been surrounded by concrete and by a very passionate, intense society, so my interaction with nature has most of the time been mediated by different kinds of technologies. I guess that I needed to do this project to get in contact with that kind of beauty and the power of nature’s changes. Now that I live in Lausanne, my balcony faces a particularly gorgeous tree that I am always expecting its transformations with the seasons, and I love all the secrets it hides and shares with me.

Garden_#8_Tulips & Lilie. Video-sculpture. Mosaic of 7 LCD screens (10” and 7”), stainless steel structure, USB-C to USB cables, and power supply.

Flowers in art carry centuries of desire, projection, and symbolic weight. How do you approach that history when you place the flower in a contemporary system of recording and mediation?

I guess it is a matter of changing the role of the flower. History has placed them as static emblems of status, power, and vanitas. At the beginning, the intention of depicting a flower was to hold a precise moment of beauty and to display a certain colonial dominion through their gathered variety. Later, in modern times, with the development of science and video time-lapse, the intention was to understand how it feels and behaves; the idea of plants as sensitive lives arises. So, having this background of possession and sensitivity, I believe that I am recognising the flower as a living being with the capability of performing, with the ability to represent a human body under constant observation, and as a life that depends on technology to exist. The work, in a sense, seeks to collide the historical becoming of flower depiction with the logics of techno-control under which our society operates.

#3_Lilies at the cold chamber. 2020. Video-sculpture. Mosaic of 5 Full HD 7” & 5” LED screens, 5 Raspberry Pi, PVC, screws, HDMI cables, and power supply.

The work creates a state of intimacy, yet also one of constant watching. How do you navigate the balance between care and surveillance when designing the camera circuits around the plant?

It is very intuitive, and yes, quite intimate. The process of installing the set is something that I don’t show that much. Each case is sort of unique, it depends on the season, the flowers I can find, my mood, the space where I am able to work. At the beginning, in Buenos Aires, the first two places where I started to work on this project were the basement of a former asbestos factory -in cheLA-; and literally in the old walk-in freezer of a former neighbourhood canteen in La Boca, by the Riachuelo -in MUNAR-; I was looking for rooms where I could close the door, leave the flowers and the security cameras working for 20 days, without being interrupted by any human presence other than me.

These spaces of confinement allowed me to create this kind of safe environment for the experiments to happen, but as I said a few times, I think the surveillance system of the cameras is quite violent, like it is highlighting something that is quite normalized in our society, that sort of “freedom/power” to record everything. In any case, that is exactly what I am looking for, that in the design of the system/circuit the tenderness and the violence are both present. I guess I try to navigate the process with admiration towards the flower that will be placed there, I take care of it since I buy and place it in the experiment, then it is just a matter of choosing how many eyes I want on it – sometimes I use 3 or 5 cameras – then I just watch from afar and wait for it to cease… but again... the more I look and take care of it, the more I’m also controlling its life.

The secret life of flowers, 2025. Exhibition view at Tomas Redrado Art. Photo by Evelyn Sosa.

At Paris Photo, your installation created a conversation between the living flower, the recorded timeline, and the recomposed digital garden. How did the context of a fair devoted to the photographic image influence your presentation and thinking?

Well, my participation in Paris Photo was in the framework of the Digital Section, and it was the first time that we – me and my galleries – were presenting the project in Europe, so the intention was to show all the faces of the project: the garden composed of the video-sculptures installed on walls and stands; alongside the surveillance station, containing the living presence of the flower.

Personally, Paris Photo presented itself as a challenging setting to question the stillness and the embodiment of the photographic image. It was a risk (worth taking) to show this series of video-sculptures, but my practice is constantly questioning the physicality of the image, and I am always interested in navigating the limits between movement and stillness. Besides that, bringing the living flower to the scene is always curious, as its performance reveals the fragility that is behind the technological pieces; particularly in the context of the Digital Section, it displayed the contrast between something that is alive and the roughness of the surrounding digital, and I guess, I wanted to keep visible that tension.

Garden_#A, 2025. Installation. Polyptych of 7 video-sculptures on stainless steel stands.

Your project at Miami Art Basel met an audience that often moves rapidly through dense visual stimuli. How did this environment shape the way you conceived or adapted the installation there?

The case of Art Basel Miami was a completely different experience. It was the first international art fair that I was doing, and also the first time the project was shown at a larger scale, so the emotions were high and all the gestures that the installation embodies appeared for the first time: the idea of composing a garden with all the pieces, to show the recording process as an installation, and to highlight the performativity of the flower. In the hurry of the fair, the video-sculptures looping continuously triggered constant curiosity, and the living presence acted as a pause—everyone played with the surveillance system, placing themselves next to the flower and taking pictures, of course. I can’t detach myself from the fact that I was so happy to be there, participating in the fair, that I guess that the work and I were as stimulated as the audience—we could say that the garden was in bloom and the bees were all around (lol, haha)

The secret life of flowers, 2025. Exhibition view at Tomas Redrado Art. Photo by Evelyn Sosa.

Technology in your work feels less like a tool and more like an active presence. How do you establish a relationship with these systems, and how much room do you allow for unpredictability or failure inside them?

I like to embrace technology as something completely natural. If we as humans are living creatures of nature, I believe that everything we create, even if it seems inert, belongs to the natural realm too. In my practice, that is the role that I want technology to have: a natural, active presence. I don’t want to hide it, even if it looks messy and rough.

Thinking about the sublime that is intrinsic to the forces of nature – something that is beautifully unpredictable and uncontrollable – if I follow what I am stating here, I guess my role/relationship with these systems is to design the conditions for cruel and tender dialogues, leaving room for erratic outcomes. I choose to love the sublime fact of technology, not to control it, but to coexist with it.

Garden_#11_Pink Lilies & Tulips. Video-sculpture. Mosaic of 7 LCD screens (10” and 7”), stainless steel structure, USB-C to USB cables, and power supply.

Even under constant observation, a part of the flower remains unreachable. How do you relate to this limit, and how does it inform the direction you intend to take in future works with nature and technological vision?

I am very thankful for the limit. I am an ambitious creature, and I guess that the part I can’t access allows me to keep wondering and imagining other possible realities – and, most of all, presents to untangle. What remains unreachable is the motor that keeps me researching. Over the last year and a half, I have put my practice and myself through the experience of the Master in Photography at ECAL. So, if I have to speak about the direction my works are taking, this context has clearly reassured that all of them are operating at the boundaries between image technology and the unknown nature of things.

At the moment, I am focusing on three bodies of work. On two of them I am using AI to reconstruct and to allow me to dive into certain memories. In the first one, departing from a personal photo archive from the archaeological site where I was born in Peru, I am working on the reconstruction of certain desert and childhood spiritual imaginaries. On the other one, I am working with the Cryptozoology Archive of Bernard Heuvelmans, diving into his visual research on unknown animals. Finally, the third project that I am working on is a series of photo-sculptures, in which I am looking at the influence that body-enhancement propaganda through social media has on female bodies and souls. There is no clear horizon where all these lines of research are taking me, but as far as I know, I am devoted to keep creating a partnership with technology to dive into the secrets of spiritual otherness.

The secret life of flowers, 2025. Exhibition view at Paris Photo ‘25.

All the pictures are courtesy of the artist, Rolf Art and Tomas Redrado Art.

Interview by DONALD GJOKA

What to read next