Malte Wilms

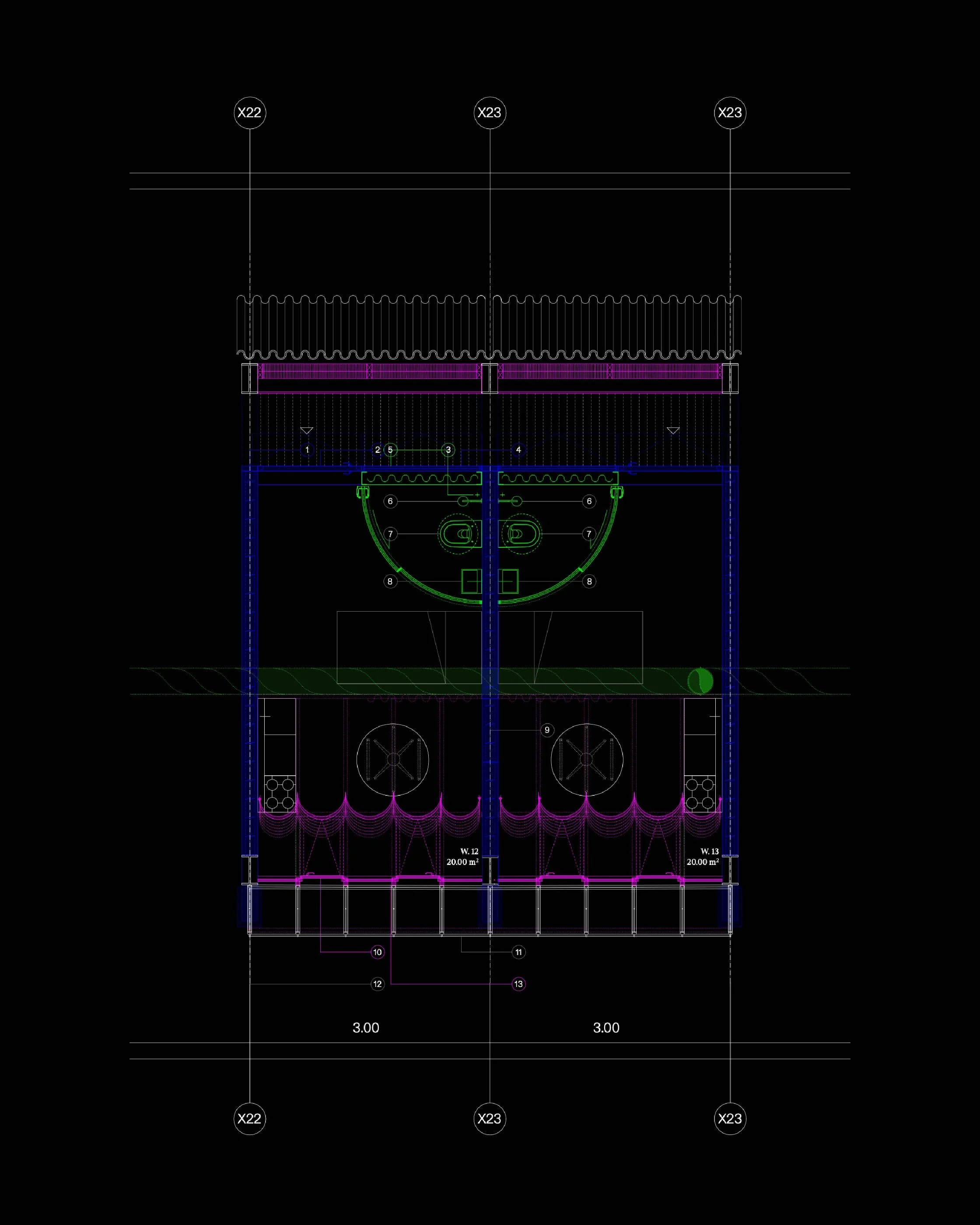

HEATSHIELD, 2024

Malte Wilms is an architect whose practice expands far beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries, moving fluidly across ecology, politics, virtuality, and material experimentation. Emerging in a moment marked by planetary and disciplinary crises, his work reframes architecture not as the production of fixed forms but as the negotiation of relations between climatic, technological, and social forces. For Wilms, architecture operates as an intelligent system that is distributed, adaptive, and intrinsically collaborative.

From his transformative project HEATSHIELD, which reconceives architecture as a trimtab capable of shifting entire environmental systems, to his ongoing research on Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map, Wilms consistently interrogates how design can sense, respond, and recalibrate. His approach rejects singular authorship in Favor of constellation-like collaborations among architects, artists, engineers, and digital intelligences.

Based in Berlin, a city he describes as a “spatial metabolism” Wilms is deeply attuned to the ways urban environments evolve through fragmentation, coexistence, and continual negotiation. Within this landscape, he sees architecture as an instrument that must move beyond economic logics toward planetary metabolism, embracing entropy, adaptability, and ecological reciprocity.

Through teaching, research, and built work, Wilms challenges contemporary architecture to act with precision yet openness, balancing rigorous analysis with poetic freedom. His practice ultimately points toward a future where design becomes a living, intelligent process capable of navigating the complexities of a post-fossil age.

HEATSHIELD, 2024

Your practice moves across architecture, politics, ecology, and virtuality. What’s the invisible thread that connects all these dimensions?

The invisible thread connecting these dimensions is an interwoven, complementary, and optimistic way of practicing architecture, an array form of thinking. Like many of my generation, I entered the field during a moment of disciplinary and planetary crises, when architecture’s role was being redefined, no longer as the production of form but as the negotiation of relations between material, climate, technology, and politics. Coming from different disciplinary contexts, I began to see architecture less as a singular authorship and more as a distributed network of interacting entities, a dynamic system in which ecological, technological, and social forces continuously negotiate one another. My practice operates as an experimental framework that examines how these interactions can be recalibrated rather than represented. The goal is to understand architecture as a form of intelligence, aligned with Buckminster Fuller’s vision of a Design Science Revolution, a systemic practice capable of sensing, adapting, and responding within the complex networks we already inhabit.

What has been the turning point project or moment that truly reshaped your creative journey?

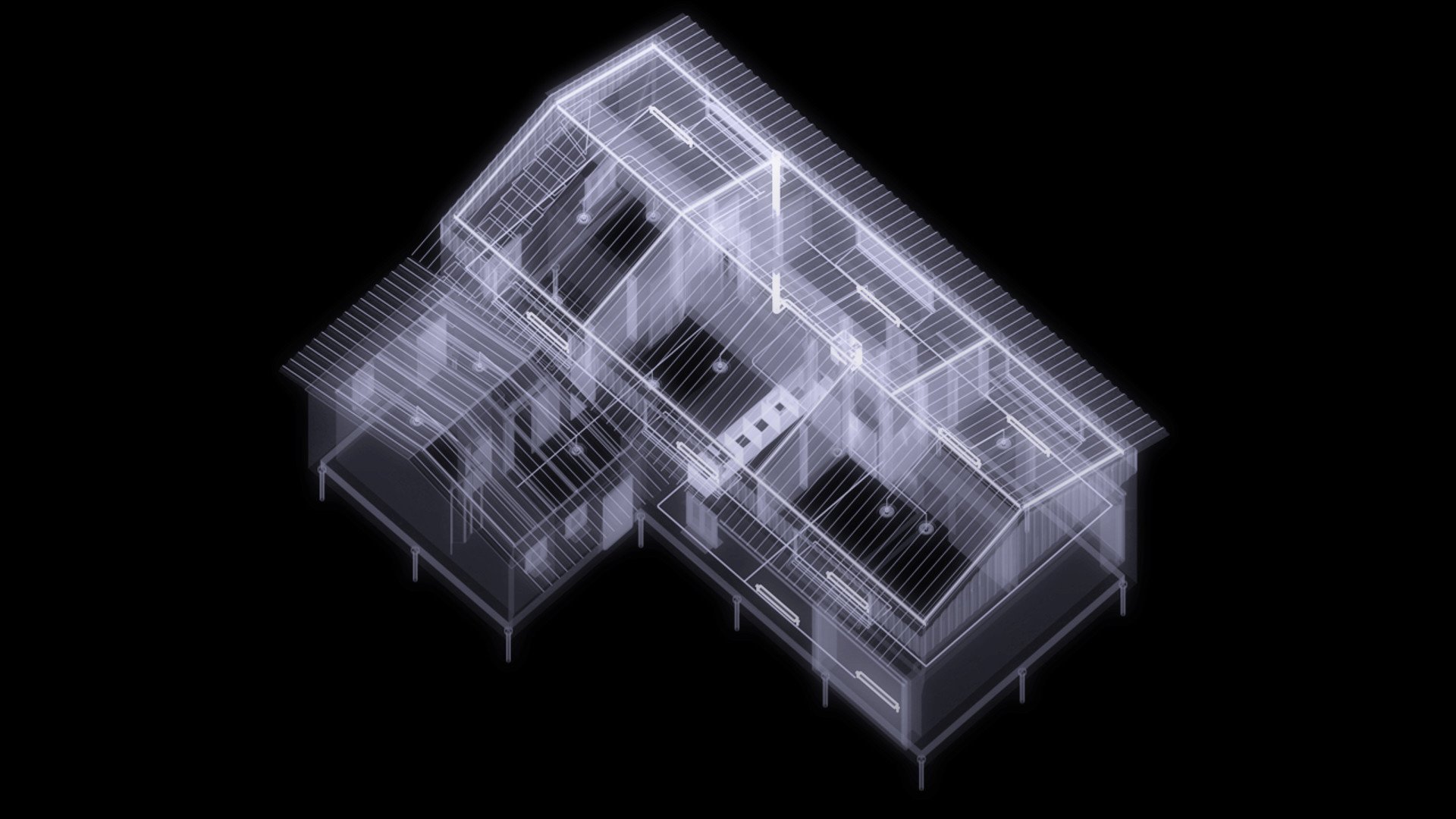

The turning point came while working on HEATSHIELD, when I understood architecture as a trimtab, a small but decisive force capable of redirecting larger systems. HEATSHIELD is an adaptive reuse project that reclaims a spatial collapse by transforming a winter garden into a sequence of inhabitable microclimates. Instead of relying on mechanical systems, it uses thermal curtains and partitions to regulate heat and light, drawing on the bioclimatic principles of Aladar and Victor Olgyay. Here, architecture becomes an instrument of calibration, translating climatic and social data into spatial intelligence. It is less about control than about responsiveness, a precise intervention that shifts the balance of an entire system.Berlin is a layered, ever-changing city.

HEATSHIELD, 2024

How does Berlin it influence the way you think and design space?

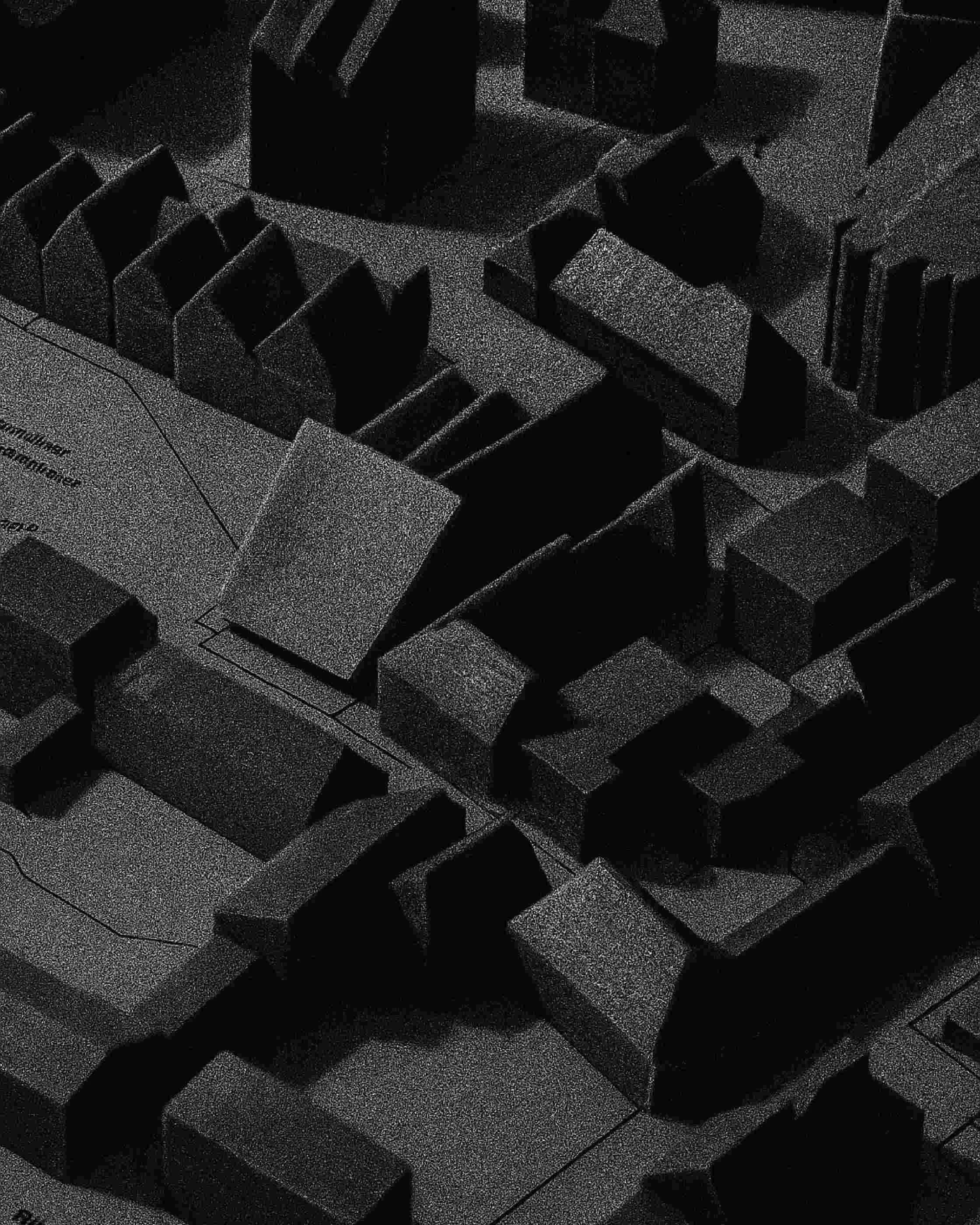

Before moving to Berlin, the city existed for me mostly as an idealized image, shaped by fragmentation. Living and working here, this image gradually unfolded into something more intricate: a territory defined less by its architecture than by its voids, its interstices, its capacity to absorb contradiction. Berlin operates as a spatial metabolism, constantly transforming its own remains. Factories become studios, housing becomes infrastructure, ruins become frameworks for new forms of life. This perpetual conversion reveals the city’s deeper logic, one that O. M. Ungers and Rem Koolhaas described in The City in the City: Berlin as a Green Archipelago. Their vision of a fragmented but interconnected urban landscape resonates strongly today, an archipelago of distinct islands held together not by continuity but by coexistence. In that sense, Berlin is not a unified city but a system of negotiations, between past and future, density and emptiness, ideology and adaptation. This condition deeply informs my work: each project becomes an inquiry into how architecture can act within this dispersed field, not as a stabilizing monument but as one more island in an ever-shifting archipelago.

HEATSHIELD – Reference: NASA Orion Heat Shield

Your work seems to oscillate between conceptual rigor and poetic freedom. How do you balance these two poles?

Instead of control, I aim for resonance, a process that allows things to find their own coherence. Each project unfolds through cross-disciplinary constellations, testing how precision and intuition can coexist. Within O’A, this approach becomes a collaborative practice in constant alteration, revealing hidden and parallel realities that shape our time, not as fixed form but as a system in continuous calibration with its environment. O’A is intentionally open in definition. It could stand for Office for Architecture, Ordinary Access or many other interpretations. It operates as an impersonal figure, a distributed practice that expands through dialogue, shared authorship and exchange. Each project connects architects, artists, engineers and digital intelligences. This reflects how architecture functions today, as a network of agents, materials and data rather than a singular authorial vision. Collaboration, in this sense, is not about consensus but about maintaining productive tension between different forms of knowledge.

Currently, I am a fellow of the Akademie der Künste Berlin in the Architecture section. Within this fellowship, I am developing an update of Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Energy Map in the form of an animation. The Dymaxion Map was originally conceived as a dynamic world map, unfolded into a network of interconnected triangles to reveal planetary relationships beyond political borders. Through animation, the map can be restored to this original intention, no longer a fixed graphic but a transformable model that expresses movement, connection and global interdependence. By integrating contemporary energetic data and climatic pressures, the project reactivates the Dymaxion Map as a living system and reframes it for the challenges of the post-fossil age.

HEATSHIELD, 2024

Architecture and visual arts often share the same languages: when starting a project, do you think more in terms of building or storytelling?

I try to avoid having a fixed image in mind. Each project begins as an open system rather than a predetermined form.I have opted for an interwoven, complementary and optimistic way of practicing architecture. To remain open and porous, I launch individual exploratory missions from this dynamic framework — sending out signals and hoping for resonance. In this sense, building and storytelling are parallel acts of exploration rather than fixed outcomes.

Much of your research deals with the relationship between physical and digital space. How is the “virtual” already redefining the way we inhabit the world?

Much of my work examines how physical and digital space have merged into a single continuous environment. The virtual is no longer separate; it shapes how we design, perceive and inhabit space. In HEATSHIELD, for example, thermal simulations were used to define spatial function, showing how inhabitable microclimates can generate architecture rather than simply serve it. The virtual expands this approach by allowing us to model complex interactions and anticipate change. It is not an abstract parallel world but a design environment with real material consequences.

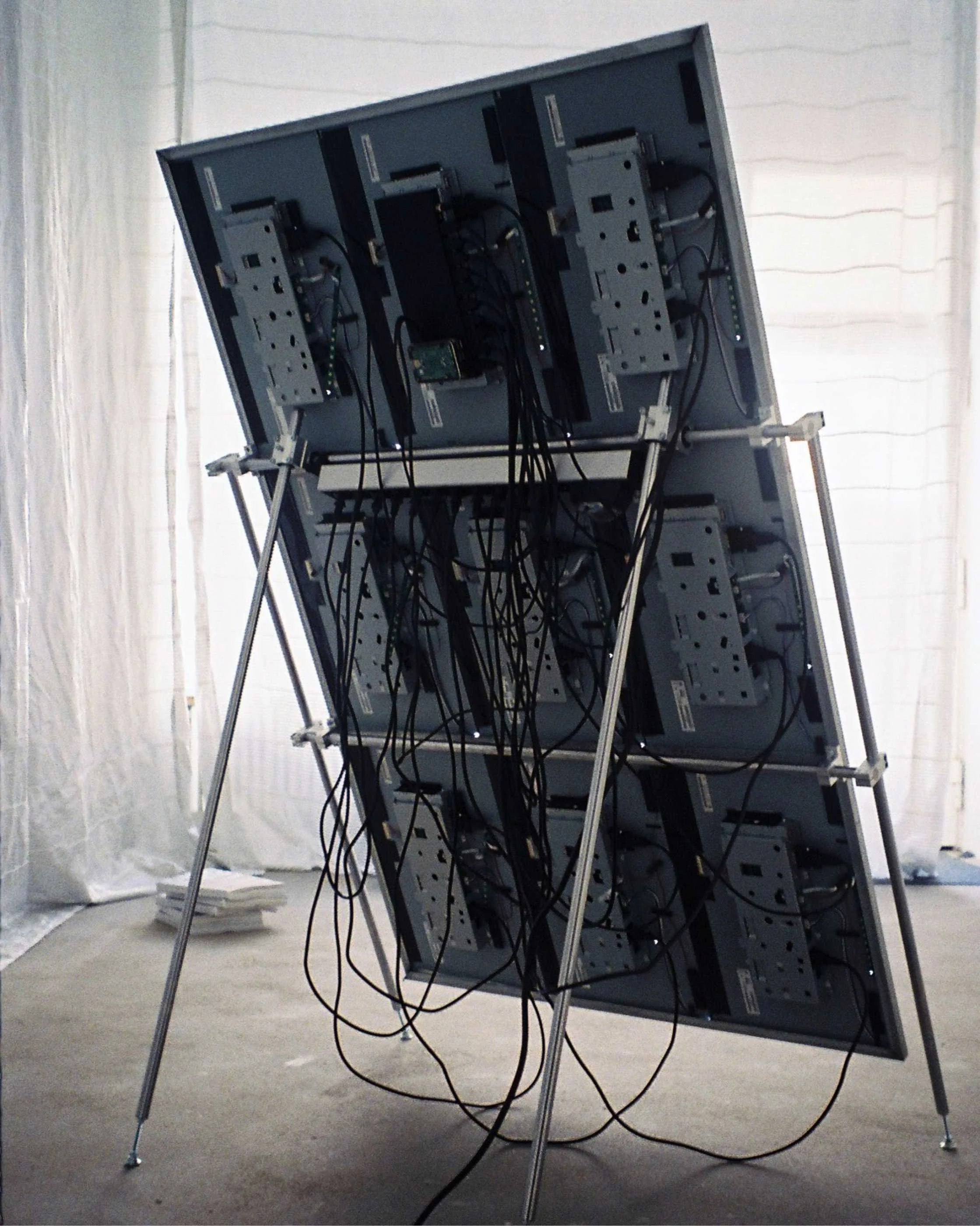

Array x Moritz Riesenbeck © Jack Hare

““Architecture is not the production of form but the negotiation of relations, material, climatic, technological, and political within a constantly shifting planetary system.””

Array x Moritz Riesenbeck © Jack Hare

You’re also active in teaching: what have you learned from your students that has changed your own approach to design?

In many ways, education should reflect the crises that define our time, ecological, disciplinary and social. Teaching at different schools, I have realized how strongly these contexts shape the way I think about space and responsibility as a container of knowledge. From this understanding, I developed my teaching and research program DYMAXION, a term introduced by Buckminster Fuller, based on three entities: Dynamic, Maximum and Tension. Students today navigate a fragmented reality, where bridging technical, ecological and cultural knowledge has become essential. This friction creates urgency, a sense that architecture must be practised differently, grounded in a critical understanding of how our environment has been constructed and how it can still be transformed.

MUSC x Chris Gansemer

In a time of ecological crisis, what do you see as the most urgent responsibility of architecture?

It must move beyond the economic, toward a planetary metabolism. We are leaving behind the carbon form of the fossil age, where cities were shaped by energy excess and industrial order. A post-fossil world may dissolve the urban form itself, shifting us toward an architecture of less comfort and greater adaptability. Architecture should learn from thermal systems, radiant exchanges and insulating layers, becoming part of the planet’s energetic balance. Seek the underlying order in randomness, an architecture that flows, adapts and regenerates.

MUSC x Chris Gansemer

If you could imagine a city of the future that embodies your vision, what would be its three defining features?

A city of the future should be generous - in its capacity to host difference and coexistence.

Unlike the Generic City described by Koolhaas in S,M,L,XL, it would not aim for efficiency or neutrality, but for openness and exchange. At the same time, the Generic City can also be read as a contradiction and a potential - a starting point for transformation rather than decline. It must operate beyond the economic - redefining value through ecological and social reciprocity rather than growth. And it should embrace entropy - understanding disorder, decay, and transformation as forms of renewal within the urban system.

O'A x DISC

Your recent exhibition Heatshield explores the intersections of climate, vulnerability, and protection. What sparked the initial idea behind this project?

The strategy of HEATSHIELD follows the principles of bioclimatic architecture as formulated by Aladar and Victor Olgyay — using solar radiation, heat circulation, and storage to create thermal comfort within a climatically demanding environment. Working within the strict heritage framework of Otto Steidle’s IBZ building, the project develops a lightweight, reversible structure that enables thermal adaptation without altering the original architecture. Conceived as a thermal prototype, it is scientifically monitored and seasonally adjustable, ensuring comfort through variation rather than control. Developed in collaboration with DISC Journal, the project extends into a forthcoming publication that situates this research within a broader reflection on thermal, ecological, and architectural transformation.

In Heatshield, the notion of shelter seems to go beyond architecture and touch political and ecological dimensions. How do you hope the audience interprets this expanded sense of protection?

In HEATSHIELD, protection is not conceived as isolation but as a cellule — a porous and responsive organism that evolves through exchange. It positions architecture as a mediator between climatic, social, and material conditions, constantly negotiating rather than separating them. Shelter becomes an adaptive field that connects human and non-human actors, rather than a boundary that excludes them. In that sense, protection is a living process — balancing exposure and resilience, comfort and transformation.

Pigsty x FW

Interview by DANIELE MENICHINI

In collaboration with DISC JOURNAL

What to read next