Open Reel Ensemble

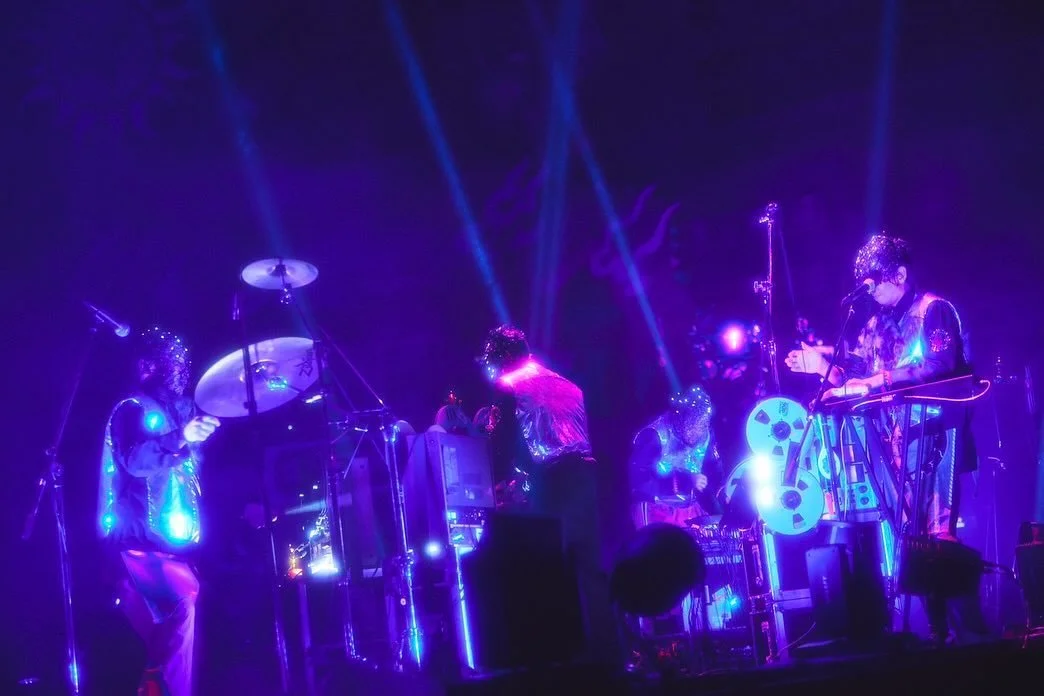

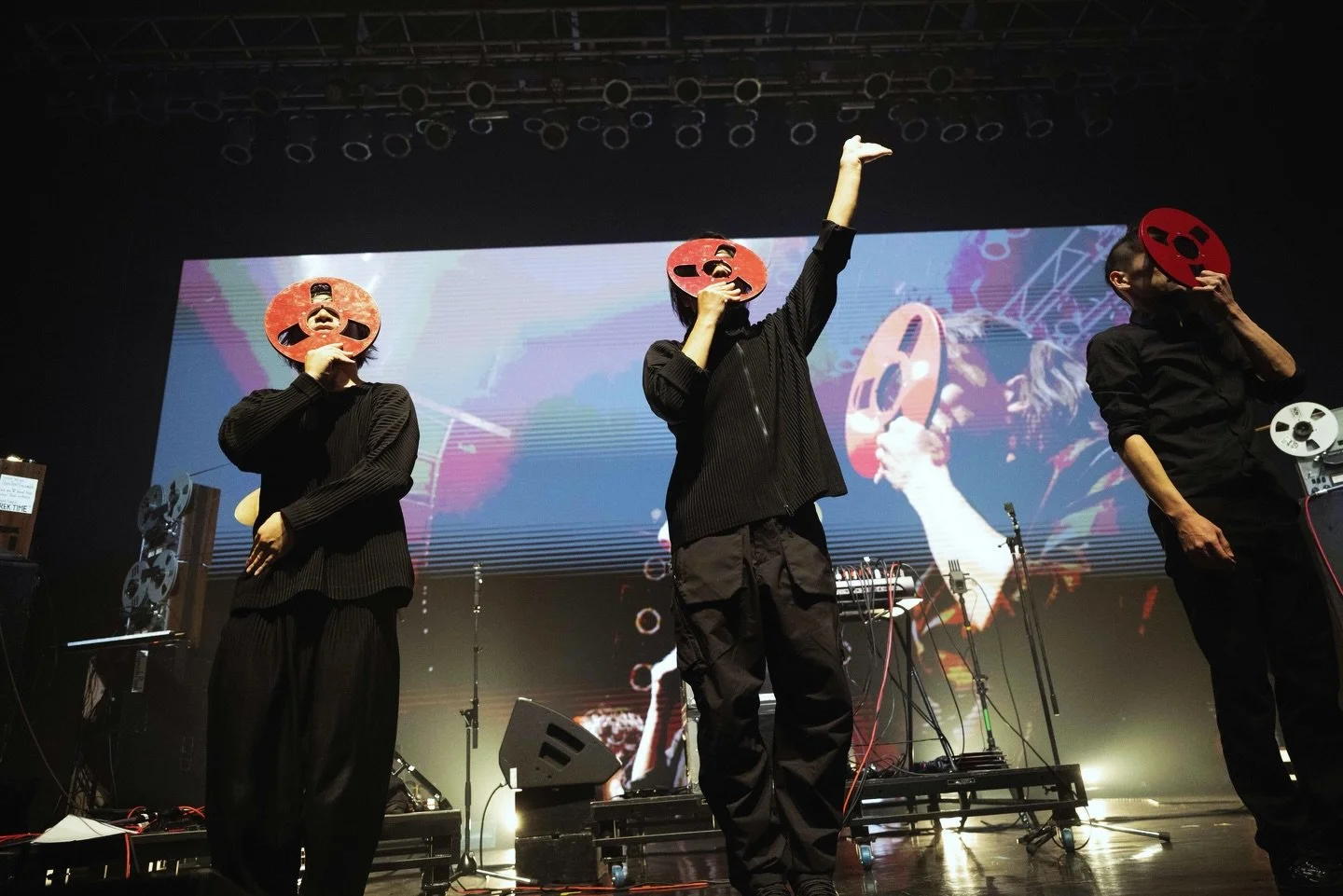

Open Reel Ensemble imagine a world built on magnetic tape. For Ei Wada, Haruka Yoshida, and Masaru Yoshida, the reel-to-reel recorder is a magnetic folk instrument and the entry point to Magnetik Punk: a parallel culture where obsolete machines become native sound.

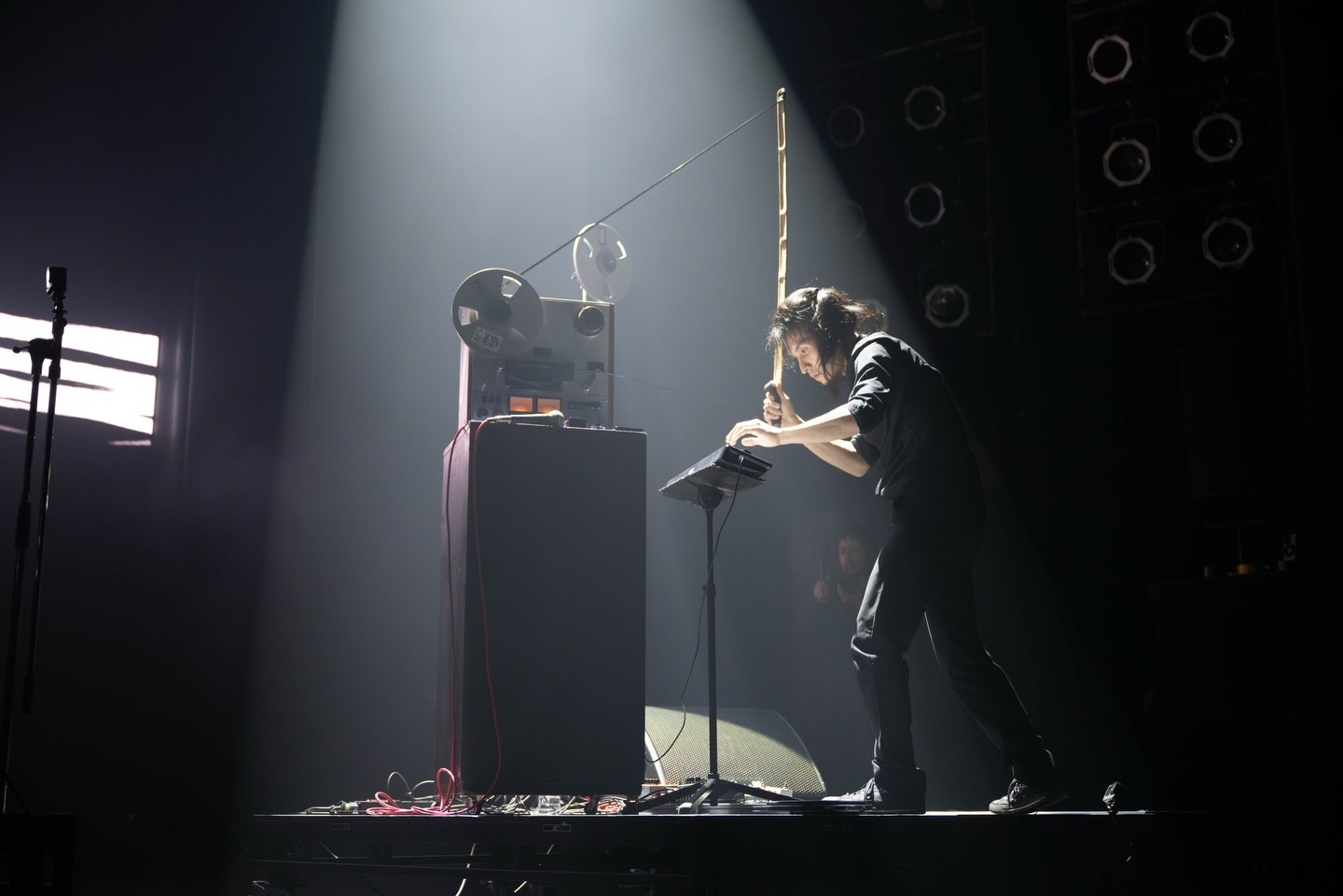

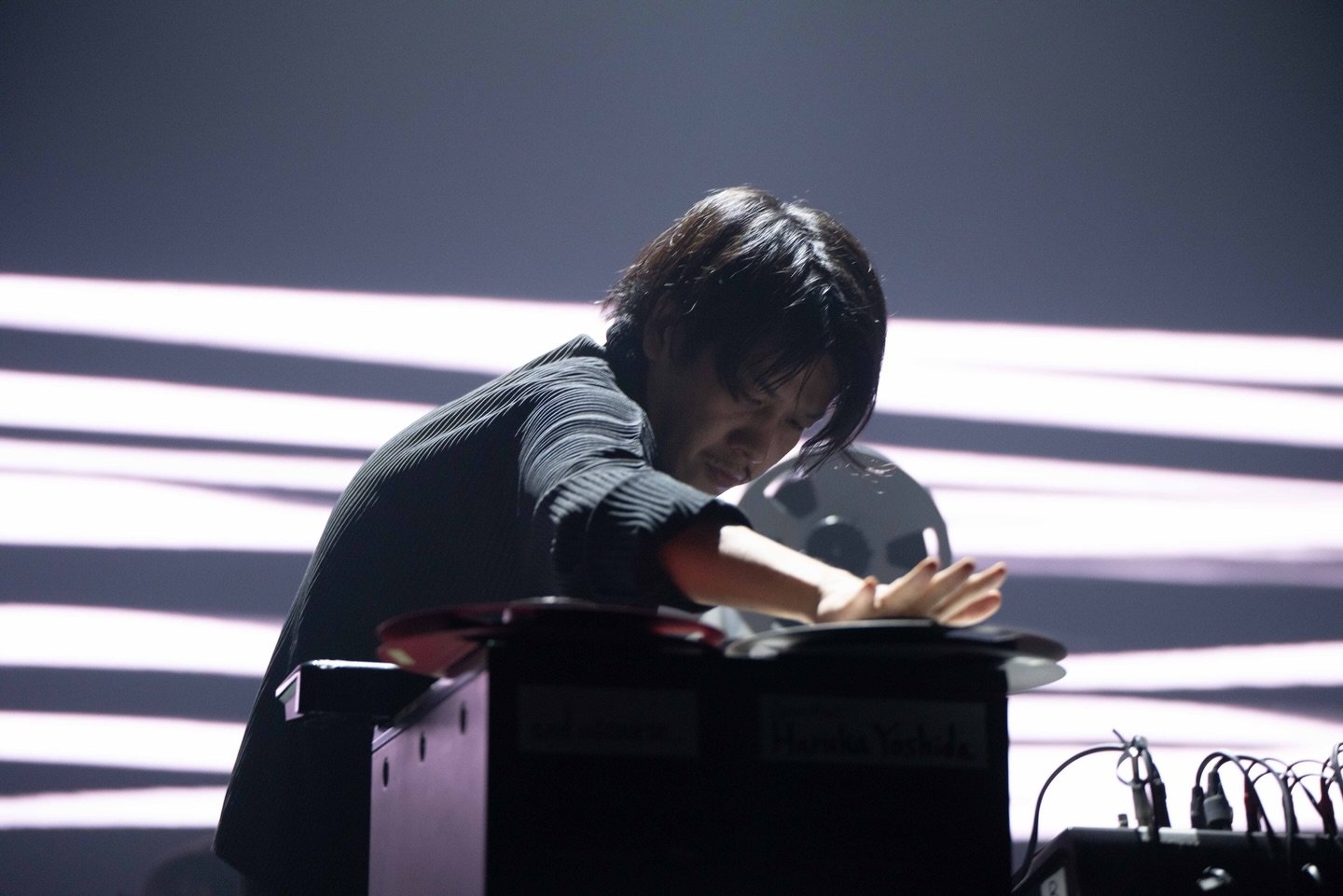

Since forming in Tokyo in 2009, the trio have developed their own language of performance: bowing tape with bamboo rods, striking CRT televisions until they resonate, looping fragments of audience noise in real time. Each gesture pushes discarded devices beyond their original function, revealing unexpected tones and rhythms. The result is raw, futuristic, and communal.

Their vision crosses disciplines. They have scored shows for Issey Miyake, and performed at Ars Electronica, Sónar, and MUTEK, bringing their magnetic sound into contexts that range from fashion runways to experimental festivals worldwide.

Kimino Musik reunites you with Tavito Nanao almost a decade after Vocal Code. What changes when a voice recorded in another era suddenly speaks again in the present?

The song that Open Reel Ensemble released this year is “Kimino Musik,” a collaboration with Japanese singer-songwriter Tavito Nanao. It was a piece that had been performed only once in a live show long ago, then remained dormant for many years.

Recently, while organizing old data on a hard drive, we unearthed the original demo recording. We refined it and released the finished version on Bandcamp.

The theme of the song is:

““Your music that crosses the gate of time and flies across the endless wilderness.””

““In the moment we touch the tape, the sounds of the past warp in real time and resound as a newly born now.””

The music video features our own film depicting an open-reel magnetic tape—a medium of magnetic recording—flying through the sky.

Every recording medium is a device that opens the gate of time. From past to future, a certain thought travels through four-dimensional spacetime. It drifts across the chaotic wilderness—perhaps reaching an unknown listener, perhaps not.

In the imaginary town that appears in the world of “Kimino Musik,” people take part in a yearly ritual where they record their voices onto open-reel tapes and throw them from the rooftops of their homes.

As the tapes are shuffled by chance, they are passed from hand to hand—a festival of recorded sound.

A hundred years after the festival began, a person who retrieved a tape for the first time in forty-six years listened to it and, among the voices of strangers, faintly heard the sound of their own childhood voice.

That person said:

““The voice I record today will also make someone’s eardrum tremble in the future. This is a relay of sound woven by chance and inevitability.””

What might be changed by this relay of someone’s feelings? The answer continues to fly, even now, toward the endless wilderness.

You describe reel-to-reel decks as “magnetic folk instruments” within a world you call Magnetik Punk. When you perform, are you channeling history, or inventing a future that never existed?

It may be an experiment in gazing into a present as error—a moment that was never meant to exist.

In the world of Magnetik Punk, open-reel tapes are, of course, played as instruments, and people fly through the air by magnetic force. Asphalt itself is a magnetic material. At dusk, when you inhale the magnetic dust drifting in the air, someone’s distant memory suddenly flashes back… That’s the kind of world it is. In the midnight clubs, people dance on huge rotating floors, wrapping magnetic tape around their bodies as they spin.

We are always guided by the question: “What kind of music would be playing there?”

By the way, in Japan, the reel-to-reel tape recorder is called an “Open Reel.” It’s not widely known, but after the invention of the cassette tape, people began calling it “open” simply because the tape was left exposed—unlike the cassette enclosed in a case. And it is because the tape is exposed that we can touch it directly—shake it, strike it, and manipulate it—turning the reel-to-reel recorder itself into a musical instrument.

As time went on, recording devices became smaller and smaller, and today it has become almost impossible to physically touch a “recorded object.” That’s precisely why we obsessively touch these relics of the past—open-reel tapes—inducing errors in their constant playback, distorting spacetime itself.

In the moment we touch the tape, the sounds of the past warp in real time and resound as a newly born now. This, for us, is the play of opening the present as error.

Glitches and breakdowns often cut through your sets. When the machine fails, something else speaks - what kind of truth do you hear in those moments of collapse?

The fact that we can perceive it as a glitch—as dance music of collapse—is because we exist outside the tape. In other words:

““The signal recorded inside itself does not change. But if you touch its container, the world begins to warp.”

”

This sensation is an intuitive hint that the open reel behaves like a TARDIS — Time And Relative Dimension In Space.

Furthermore, it is said that this universe we live in also bends spacetime through gravity and acceleration.

If that’s the case, then perhaps this very world, too, is some kind of medium.

Your practice turns obsolete machines into bodies that respond to touch: bowing tape with bamboo, spinning reels by hand, striking machines. Do you discover these methods through intention, or by listening to what the machines want?

We press a stethoscope to the machines, observe them closely, and run our hands over every inch—searching for where their hidden voices lie. When we do, we sometimes encounter sounds we never imagined they could make.

We also choose to actively amplify accidental flashes of inspiration. For example, a bamboo rod my grandfather used for his stiff shoulders happened to catch my eye; when we stretched magnetic tape across it, a technique emerged for playing the tape like a bowed instrument. Even now, I’m sure there are countless things we’ve overlooked—and countless sounds we haven’t yet heard.

Your instruments don’t just make sound; they seem to alter the atmosphere itself. How do you think about space - a runway, a gallery, a festival - as part of the instrument?

In Open Reel Ensemble’s live performances, we sometimes record the sounds of the moment—voices of the audience or noises in the space—and process them in real time as part of the performance. A voice or sound that existed only once in that moment begins to loop, transform, and layer upon itself, gradually building the music.

The microphone acts as a portal connecting the tape and the outside world. Through that portal, the real spacetime around us becomes part of the instrument itself.

At Expo 2025, Ei Wada also staged an Electromagnetic Bon Odori with Electronicos Fantasticos!. Did that experience of blending ritual and electronics influence the vision of Open Reel Ensemble as well?

Ei Wada, founding member of Open Reel Ensemble, performed at the Osaka–Kansai Expo 2025 under his project ELECTRONICOS FANTASTICOS!, where he resurrected retired home appliances as electromagnetic instruments. Together with nearly a thousand participants, he created a great circle of dancers, transforming the event into a kind of electromagnetic folk ritual.

At the center of the stage stood a large vintage CRT television. By picking up the electromagnetic noise emitted from its screen, they struck the TV like a taiko drum, turning it into the core of the beat and letting it thunder at full volume. There is a clear resonance between the two projects, each influencing and expanding the other.

What they and we play are obsolete technologies—dead tech that has outlived its original purpose. Once freed from the pursuit of convenience, these machines become entities that voice their own electromagnetic sounds. From them emerges an ongoing experiment: the weaving of “electromagnetic folk music.”

Amplifying the heavy, physical voices of old machines—an act that is by no means efficient— this experiment instead seeks a festival of technological rewilding, something possible only because of its very inefficiency, reviving the primal energy of technology within the modern city.

From Ars Electronica to Sónar and MUTEK, your music has appeared in very different contexts: art festivals, club stages, fashion runways. How does the setting shape the way you approach performance?

The people involved are the ones who weave the story. Through dialogue and collaboration with others, our performances and music evolve—changing like living organisms.

As we catch each ball that comes our way, we add our own interpretation through magnetic music, and then throw it back once again.

Your machines won’t last forever, but the culture you’ve imagined around them might. What part of Open Reel Ensemble do you hope will outlive the reels themselves?

When reading a musical score, there’s always the option to change how you read it. Hidden sounds and unseen music are always right beside us.

Interview by Stefania Bonomini

What to read next