Richie Culver

Richie Culver’s forthcoming album I TRUST PAIN, set for release on October 31 through Rainy Miller’s Fixed Abode, marks an important moment in the artist’s practice. Known for painting, photography, and performance as much as for music, Culver’s work has always resisted containment within one medium. With this record he consolidates years of experimentation, drawing a direct link between his visual practice and his sound. Each track relates to an artwork he has exhibited over the years, not as a translation but as an act of tension. The connection is emotional, disruptive, and autobiographical. Sound and image grind against one another, forming a raw continuum that expands the scope of his practice while remaining deeply personal.

The record opens with a sample of war reporter Jake Hanrahan, taken from the Popular Front podcast. Asked what the underground means, Hanrahan replies that it is what happens on its own, as culture and lifestyle, without regard for the mainstream. This answer sets the tone for Culver’s record, which finds its gravity in the lived experience of the margins rather than in theoretical distance. His work, both in galleries and in clubs, has always carried this sense of friction: the awareness that life lived on the edge is not simply subject matter, but a condition.

Musically, I TRUST PAIN draws on trap, spoken word, noise, and ambient. Production is shared with Rainy Miller, Blackhaine, and Bitter Gold, three figures equally invested in constructing sounds that resist clean categorisation. The palette is heavy with distortion, dissonance, and fractured rhythms. Trap hi-hats cut through thick layers of noise, while Culver’s voice fractures across accents and registers. At times he leans into a flat, spoken cadence, at others his voice twists into falsetto or guttural distortion. This shifting vocal presence becomes a central motif: a reminder of identity as unstable, always in flux.

““The phrase I TRUST PAIN functions not only as a personal declaration but as a cultural insight into how we assign authenticity to emotional expression”.”

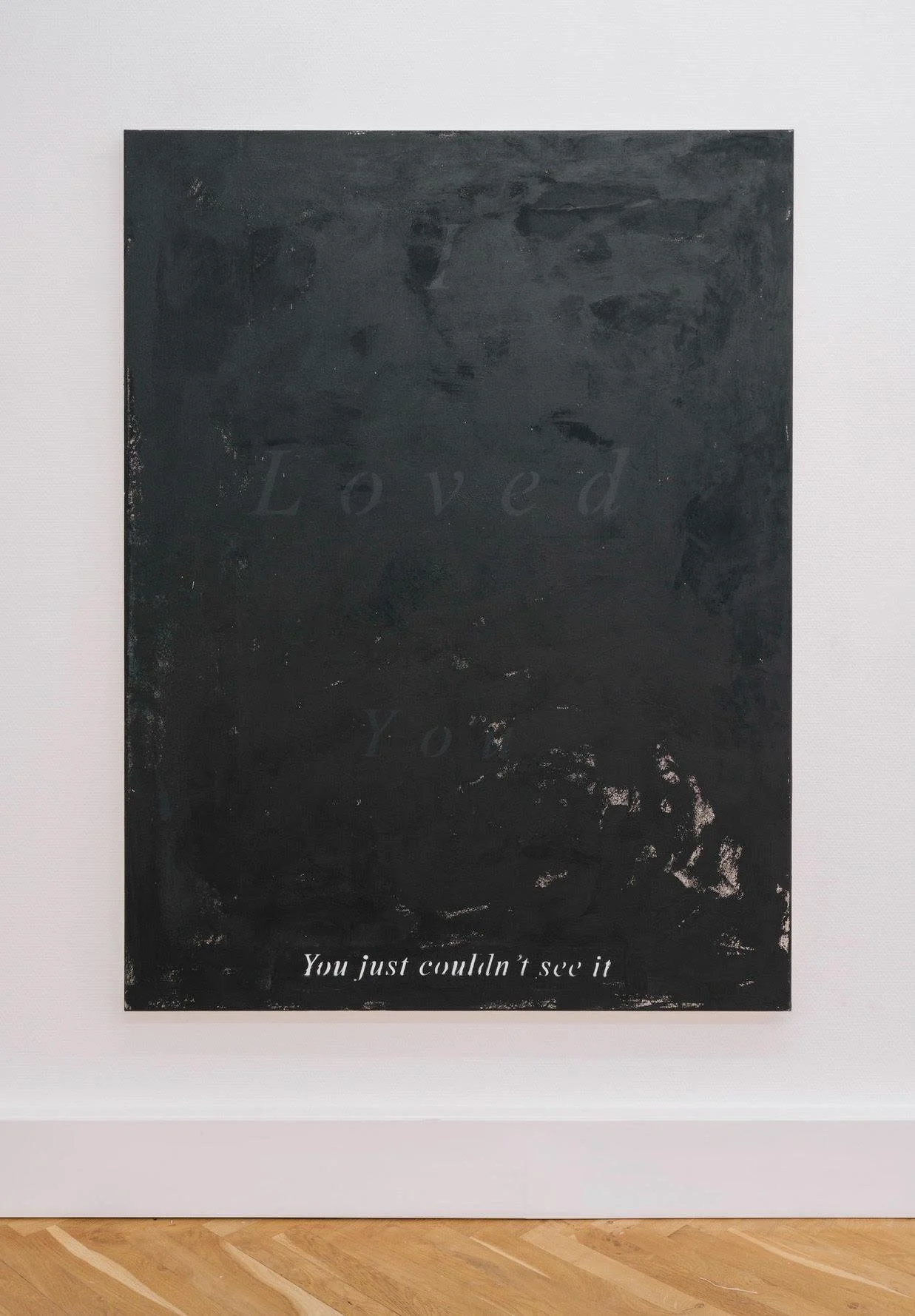

His approach to music is inseparable from his background as a visual artist. His paintings and installations often included fragments of text that could be read as slogans or mantras, but he has explained they were always fragments of songs not yet written. I TRUST PAIN realises this conceit fully, taking words once scrawled on squat walls or canvases and reanimating them through sound. What results is a record that functions as both music and archive: a chronicle of displacement, survival, and persistence.

With I TRUST PAIN, Richie Culver affirms himself as one of the UK’s most uncompromising artists, capable of bridging visual and sonic forms into a practice that feels immediate, unsettled, and vital.

Looking at both your art and your music, there is always a sense of instability, unfinishedness, refusal to settle. Do you view that restlessness as a burden, or as the core of your work?

I don’t really see restlessness as a burden so much. Instability and unfinishedness are ways of resisting closure, whether in painting, writing, or sound, because closure feels false to lived a experience. What looks like incompletion is, to me, an ethical and political choice: it resists polish, refuses commodifiable clarity, and keeps the work alive as process rather than product. Restlessness, then, isn’t a problem I wrestle with; it is the very condition that makes the work possible.

I TRUST PAIN is built around connections between your visual works and music. How did you decide which pieces of art to translate into tracks, and what kind of friction did you want to create between the two?

I’d always wanted to do this - Bring my visual work alive via sound. Some of them were text based work that were ready to go - like “I TRUST PAIN”, that was a word based painting m, as was “I loved you” and “Nothing”. The decision wasn’t about direct translation so much as resonance. Certain images carried a sonic charge, and I pursued that energy into sound. I wanted the friction to come from misalignment, the visual refusing to neatly illustrate the musical, the track resisting being a soundtrack. That gap, that tension, creates a third space where the work stays unsettled and alive.

The record opens with Jake Hanrahan’s definition of the underground. What does the underground mean to you personally, not just as an artist but as someone who has lived on its margins?

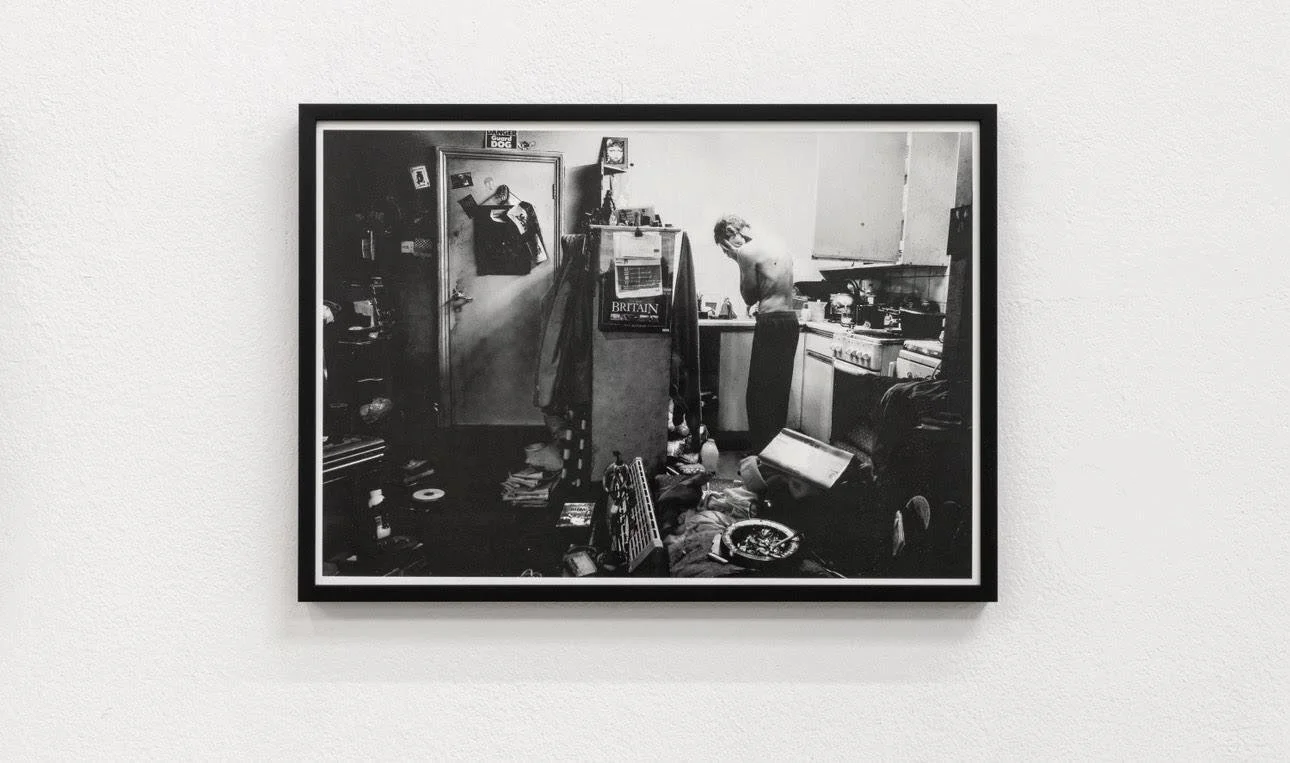

For me what comes to mind is a dirty floral bedsheet over the window as curtains, no electricity, dirty mattress on the floor, a doctor’s appointment on Wednesday and the world at your feet.

The single Chase Money reflects on constant displacement and the impossibility of outrunning the self. How did that cycle of movement shape your voice, both literally and artistically?

It’s never ending - The cycle of movement stripped away any illusion of stability. My work emerged from that, unsettled, carrying the weight of things I left behind. Artistically it pushed me toward honesty: you can’t outrun yourself, so the work becomes about confronting the fragments you carry wherever you go.

Your voice on the album shifts between registers, spoken, distorted, falsetto. Do you treat the voice as another material like paint, or is it closer to autobiography?

For me the voice is both material and autobiography. Like paint, it can be stretched, broken, distorted, pushed beyond recognition. I felt uncomfortable at first to push my spoken-word into almost rap - but eventually I came round to it.

Collaboration with Rainy Miller, Blackhaine and Bitter Gold adds intensity to the record. What drew you to work with them, and how did their approaches affect the texture of the album?

I’ve worked with them many times. I could write forever about their talents and genius, but most people know anyway.

: )

You have performed in spaces as different as Berghain, basement bars, and Camden Arts Centre. How does the setting change the way your music exists in the moment?

The setting always alters the work: scale, acoustics, and context transform how the music is received. What feels monumental in one room can turn fragile or confrontational in another. The sound remains the same, but its existence is entirely shaped by the space that contains it.

Trap, noise, ambient and rap all appear on this record, but never as genre exercises. How conscious are you of resisting musical categories?

I don’t really set out to resist categories so much as ignore them. Genres can be useful markers, but they collapse under lived experience. What comes through in the record isn’t an exercise in style but an attempt to let sound follow thought and circumstance. If that unsettles genre boundaries, it’s because the work refuses to be reduced to a single frame. I’m happy for it also to sit under Rainys - Northern Gothic movement perhaps.

Interview by DONALD GJOKA

What to read next