Venice Biennale 19th International Architecture Exhibition

The Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 is many things at once. Curated by Carlo Ratti, Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective brings together a vast network of thinkers and makers: over 750 contributors from all walks of life. Architects, scientists, farmers, artists, coders, chefs. It spreads across the city: Giardini, Arsenale, Forte Marghera. 300+ installations, 11 collateral events, and dozens of side projects. Robots, trees, thermal sensors, poetic diagrams, utopian maps. Some works are tiny and fragile. Others flood entire rooms.

What holds it all together? Not a theme, but a method. A rhizomatic layout. No center, no linear route. Connections matter more than conclusions. The show reflects today’s complexity, and our fractured attention spans. Visitors move through four sections: Natural, Artificial, Collective, and “Out.” Each asks how we live now, and how we might live better. Not in theory, but in practice. In material. In community.

Rather than presenting answers, this Biennale asks: What if intelligence is simply the ability to adapt with limited resources? What does it mean to “know” something in a time of crisis?

Overstimulation is part of the setup. Too many things at once. Too many signals. It feels familiar. Like the internet. Like daily life. Like the world we’re building.

May 10 – November 23, 2025

Venice, Giardini, Arsenale and Forte Marghera

The 19th International Architecture Exhibition, titled Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective, curated by Carlo Ratti, will be open to the public from Saturday, May 10 to Sunday, November 23, 2025, at the Giardini, Arsenale and Forte Marghera.

The Exhibition includes over 300 contributions from more than 750 participants: architects and engineers, mathematicians and climate scientists, philosophers and artists, cooks and coders, writers and carvers, farmers and designers, and many others. Installations, prototypes, robots and experiments are spread throughout the Giardini, the Arsenale and other areas of Venice, along with 11 collateral and experiential events.

Intelli/Gens: already from the title, the exhibition presents itself as a foundational reflection on the near future, a subject of study and debate for the scientific and artistic community and for the general public. It is a true laboratory of theoretical research, as well as of art and projects, within a dialectical arena between different disciplines. The display is deliberately networked: whether neuronal synapses, social networks or the internet, the rhizomatic structure ensures the centrality of every periphery, the interchange of nodes, and the coexistence of different viewpoints. Intelli/Gens, where the duality of nature vs. artificiality is surpassed by the merging of civilization and environment.

The invited participants are groups of thinkers, listed strictly in alphabetical order, as is standard in scientific articles. They are architects, engineers, biologists, scientists, philosophers who share their knowledge to find useful and functional solutions. To the hierarchy of the pyramid, Ratti substitutes – as he explains – the rhizome, as both a hermeneutic and operational approach.

The Exhibition is organized into three main sections: Natural Intelligence, Artificial Intelligence, and Collective Intelligence, plus a final section “Out,” which asks whether space (or outer space) can be seen as a solution to earthly crises.

The design of the exhibition spaces is modular, fractal, intended to allow dialogue between large and small-scale projects, to place very different approaches in direct comparison. A “Living Lab”: Venice is not just a backdrop, but an active site: with widespread installations, urban interventions, climate experiments, and real interaction with the territory and community.

The mission of this edition is to open up the curatorial process: the central curatorial exercise at the heart of this Biennale was Space for Ideas, a call for proposals from people around the world, which evolved into a platform of feedback and iteration between the Curator and the participants, a process that demanded a new approach to authorship. Space for Ideas was an experiment aimed at replicating spontaneity, considered a distinctive trait of intelligence in its various forms. The resulting group of participants spans several generations, from seasoned professionals still innovating at ninety to recent graduates just beginning their journey.

“As inspired by Rem Koolhaas's approach to the 2014 Architecture Biennale, we tried to create thematic consistency across National Participations, within the framework One Place, One Solution. We invited each nation to reflect on architectural strategies rooted in their local context, yet relevant to global challenges,” as stated by Ratti.

The Rhizome takes the stage: a localized model with global-scale application

Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective: the theme of the Biennale, which aligns the Latin “intelligens” with the multiple forms of knowledge available to humanity. A title that evokes not only individual intelligence, but a kind of knowledge that is shared and interconnected, present. The Biennale unfolds across the national pavilions located between the Giardini, the Arsenale, and some scattered sites in the city, but this year the entire project is especially concentrated in the Corderie of the Arsenale due to the closure of the Central Pavilion at the Giardini.

The title, a neologism whose final part, “gens,” means “people” in Latin, is an invitation to engage with intelligence beyond the current narrow focus on AI and digital technologies, and to show how we can adapt to the world of tomorrow with confidence and optimism.

In times of change, architecture must rethink authorship and become more inclusive.

It must become as flexible and dynamic as the world we are designing, living in, and sharing.

Global temperatures are rising while global populations are declining: visitors move through three thematic worlds, each of which proposes its own experiments in adaptation: Natural Intelligence, Artificial Intelligence, and Collective Intelligence. We are beyond merely reducing the effects of climate change: adaptation is necessary. In a world marked by fires, droughts, rising sea levels, Venice itself is presented as a “living laboratory” for these experiments.

Another key point: the circular use of materials and the aim to reduce impact and waste; pavilions are modular, prefabricated, made with recycled or reused materials, designed to be dismantled: a clear statement in favor of the circular economy.

"Architecture has always been a response by humans to a hostile climate”: this is how the current edition is introduced. From the first primitive huts, human design has been guided not only by the need to find shelter and survive, but also by optimism:

“Our creations have always aimed to bridge the gap between a harsh environment, the safe and livable spaces we need, and the kind of life we want to live. Today, as the climate becomes less forgiving, this dynamic is reaching a new level. Over the last two years, climate change has accelerated in ways that even the best scientific models did not predict.”

Adaptation requires a fundamental shift in architectural practice.

This year’s Exhibition, Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective., calls for collaboration between different types of intelligence in order to rethink the built environment together.

Are we still able to critically process what we receive?

The themes of this Biennale have largely focused on the omnipresence of technology: an expansive understanding of intelligence, which includes the "Natural" and the "Collective", remains tangible.

A multisensory Biennale, playing with the idea of "adaptation", both social and natural, a “smart” ability that clearly responds to a global critical condition.

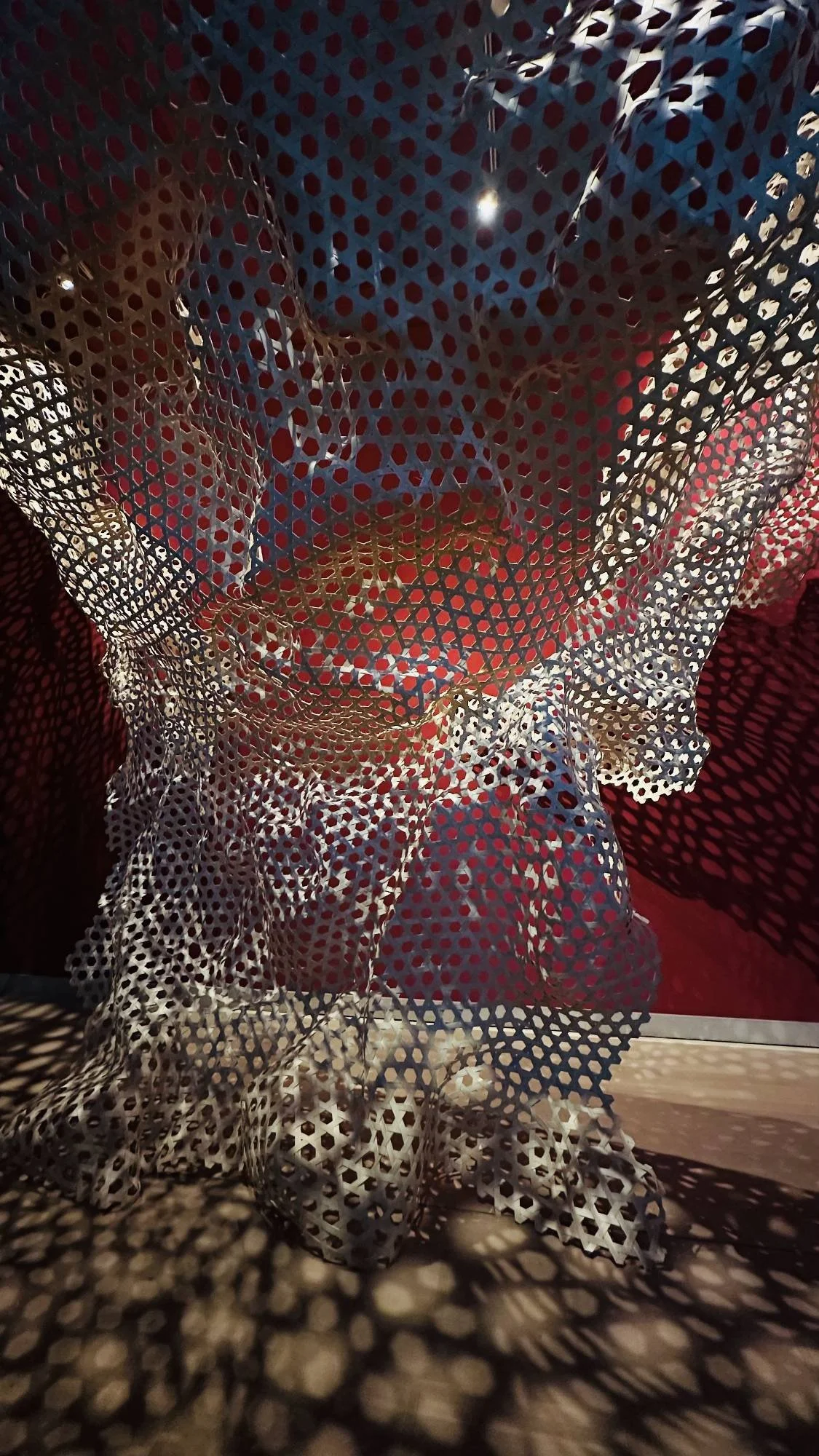

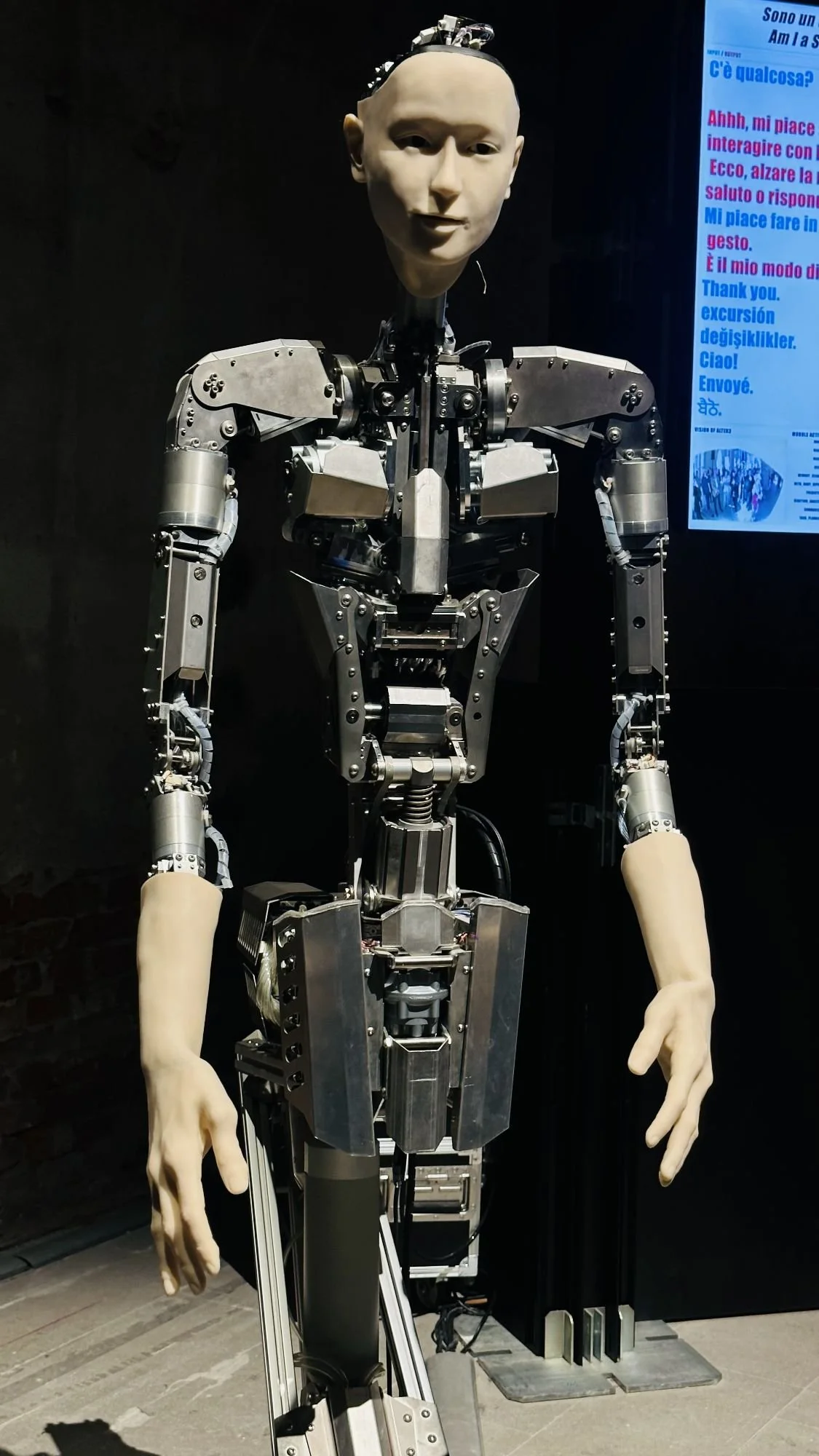

This underlying current comes to the surface through visitors’ “low-tech” interactions: sensory input, encounters with animals, and community involvement. Installations, case studies, talk corners and in-depth discussions: technology is everywhere. We saw robots, 3D printers, conceptual maps, utopian (and non-utopian) projects, experimental terrain, and transformative resources. This theme is reflected everywhere: in the display, in the selected projects, in the spaces, in curatorial thinking, in maps and scientific research.

What results is a saturated, frantic space: projects, texts, and installations of various kinds and formats overlap without hierarchy. As soon as we enter, we are overstimulated, overloaded.

Exactly as it happens in our minds (and we are beginning to observe this critically—not just recognize it, which is already a first step), overheated between screens, noise, software, connections—in a constant informational (and emotional) overload.

Where are the details? Do we still notice them?

To attentively visit every pavilion of the Biennale, at least one full week would be needed.

The doubt that arises is whether events of this size are still suited to our time, and whether it might be more useful to rethink events focused on more specific topics.

The exhibition breaks down the boundaries between disciplines and skillsets, and it seems that the architect can (and must) ackle the major issues of our time by engaging in experimentation and by working with many different kinds of knowledge.

However, in real life, the role of the architect and the culture of design weigh very little in shaping the built environment. Today, the true major issue of this profession is the risk of social and cultural irrelevance.

Each installation is accompanied by heavy explanatory texts, each one followed by a summary generated by artificial intelligence. The result is that visitors take photos of the explanatory panels with their phones, planning (maybe) to read them later.

Sensory inputs, physical, experiential, maps of shared knowledge

300 installations, 66 National Pavilions and 11 collateral events: a great concentration of ideas and experiments. Places, sounds, scents and weather conditions: projects that depend on immersive and multisensory participation of visitors for full effect. While most installations discourage hands-on interaction ("do not touch!"), tactile feeling reigns supreme.

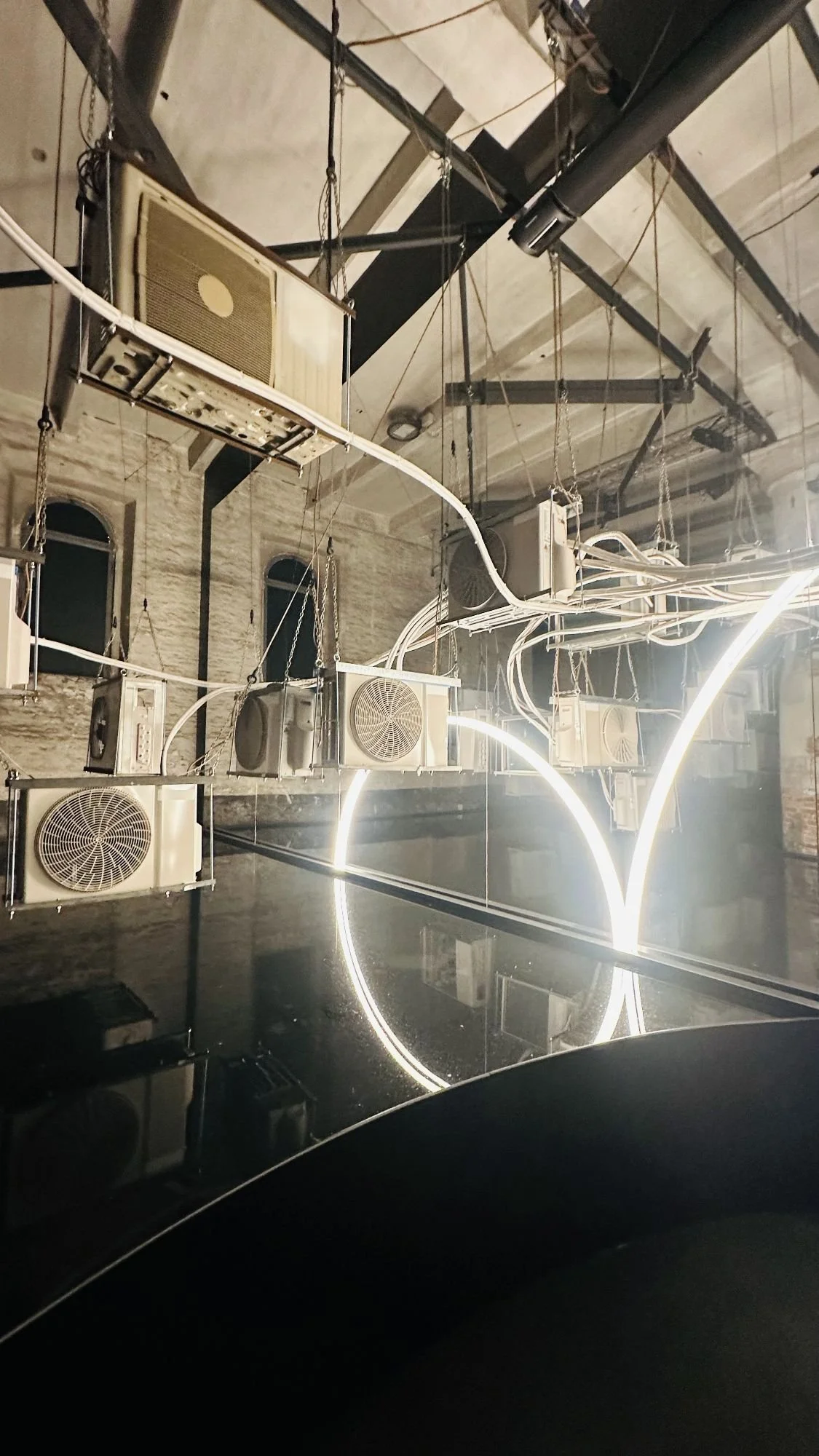

Climate is a dramatic and urgent theme for contemporary architecture.

The first hall opening the Corderie of the Arsenale is emblematic of an important theme of this Biennale: climate, heating, deformation. The first hall is devoted to The Third Paradise Perspective, an installation by the Pistoletto Cittadellarte Foundation that reflects on human impact on climate warming. The phenomenon is interesting because, indeed, the phenomenon: one feels the heat on the body, the discomfort in body and mind, while crossing the large hall, very dark, with raised water mirrors: dozens of external units of as many air conditioners produce all of the heat, and water is their waste. A glimpse of the future expected climatic conditions of Venice while one moves under the suspended air conditioning units, finally emerging into the cool, bright, lowhumidity interiors of the Corderie where hundreds of shows await.

The other works in the Arsenale are a great accumulation of content and of installations, crammed in the Corderie. Hybridization and multidisciplinarity, science and philosophy, the projections into the future, the dramatic imbalances of resources in the world, climate, desertification and absolute poverty and the thousand ways of using artificial intelligence to deal with these themes have occupied the available space, leaving very little to architecture. They are art, proposals, studies. But only proposals, indeed.

Immersive phenomena continue with installations that wrap visitors in sound: dripping water, majestic music, electronic music to examine the relation between 3D audio and architecture. Inside a space lit by glowing blue lights, visitors undergo soundtracks that evoke different "sound architectures", like that of a cathedral or, perhaps, of a disco. Other exhibitions and installations involve perceivable smells. However, in many circumstances, distinguishable aromas become integral parts of a certain project. For example, in the Belgian Pavilion we find a dense concentration of indoor plants that produce microclimate, and odors. Or, in the Mexican Pavilion, the rectangular blocks of earth (chinampa) evoke shallow water environments in which these landscape elements that traditionally float traditionally. The shows are visually different, with intriguing dynamic elements and structured surfaces: smoke, water, lava, wood, vegetation, to capture attention.

In the German Pavilion film is in the foreground, in others physical or intellectual stress tests are proposed (heat maps, robots or mannequins that do not speak, alarming news, infrared on urban centers all over the world…) or critique of design, or minimalist descriptions of AI that appear. Many screen references tell us of waste from industrial societies (clothing, car parts and other), repairing them, altering and reusing them to make a sustainable system that transcends conventional consumption models.

Have the critical shades been lost? Is it a comment on human capacity for attention? Does architectural discourse really require such marginal notes? Perhaps, too much informative material has overheated us without really letting us enter into the heart of any of the (important) themes, already barely accessible. A “low power mode” for the mental resistance of visitors while they undertake this event of endurance.

Brief panorama on the most cited Pavilions, and why

German Pavilion “STRESSTEST”, curated by Nicola Borgmann, Elisabeth Endres, Gabriele G. Kiefer, Daniele Santucci, the project is conceived as immersive experience divided into two sections: STRESS and DE STRESS. In the first, the visitor lives the reality of extreme urban heat, with “oppressive” spaces, impermeable surfaces, high thermal mass materials, lack of shade, in the second the visitor finds and tries out strategies of adaptation, mitigation, urban regeneration, green, shading, nature integrated in the urban fabric. The whole pavilion is powered by a photovoltaic system which is declared to be the first installed on a historic building in Venice. STRESSTEST manages to make physically tangible the theme of climate change, not only with models, theoretical or aesthetic proposals, but with sensations, sensors, temperatures, immediate comparisons between presence and absence of mitigation. This leads the visitor to be not a passive observer, but protagonist — a mode that many critics had been hoping for.

Canal Café – Diller Scofidio + Renfro, together with Natural Systems Utilities, Sodai, chef Davide Oldani, Aaron Betsky. It was awarded the Golden Lion for the best participation in the international exhibition. The project provides for purification of the water of the Venetian canals so as to serve coffee to visitors. It is an idea that blends technology, public utility, symbolism: Venice that lives on water, scarce resource, but possible regeneration.

Bahrain Pavilion – Heatwave: winner of the Golden Lion for the best national participation. Curated by Andrea Faraguna; engineering by Mario Monotti and Alexander Puzrin. The theme is exposure to extreme heat: the pavilion proposes traditional methods of passive cooling adapted to challenging climatic conditions, modular structures, integrated in different urban contexts. Even though at the Biennale it was not possible to dig geothermal wells etc., the proposal remains explanatory.

Belgium – Building Biospheres: one of the most cited national pavilions. Curated by Bas Smets with Stefano Mancuso (plant neurobiologist). The pavilion is a sort of miniforest with sensors to regulate climate, light and ventilation in real time; many subtropical plants, living inside architecture making the building itself a “living” organism.

Croatia – Intelligence of Errors: the Pavilion of Croatia studies error as a design resource. Instead of correcting everything, errors are studied as phenomena which arise from human–nature/technology interaction, as occasions for more adaptive, inclusive design that recognizes complexity.

Serbia – Unravelling: pavilion with pure wool fabrics, suspended segments, catenary shapes. A poetic project, recalling craft tradition, but in contemporary key, fragile, unstable, fluid.

Estonia – Let me warm you: the Estonian pavilion focuses on thermal insulation, treatment of the building envelope, critical question how much the sum of European policies on energy and insulation is really effective on the social and spatial level. Facade covered with insulating panels, to provoke a reflection on daily realities vs global goals.

Alternative Urbanism: Self Organized Markets of Lagos (Tosin Oshinowo) – had a special mention: it observes how selforganized markets in African cities are real forms of urbanism that challenge strict planning categories; informality, community, adaptation are interwoven.

Elephant Chapel by Boonsem Premthada Architecture: a small chapelarch built with bricks made of elephant dung. It is cited as example of biomaterial and as playful but serious form of reuse, of using “waste” materials with dignity and constructive function.

“Map of Glass” by Barkow Leibinger and capattistaubach: a “biodigital” installation that uses recycled glass and organic cement to build a topographic map of Venice, highlighting structural fragilities, memory, thermal flows.

Holcim + Alejandro Aravena / ELEMENTAL: prototype of resilient sustainable housing, built with lowcarbon concrete and other modern materials; presented in the Giardini Marinaressa as part of the collateral events. A way to address concretely the housing + climate crisis.

In good and in bad: international reviews

First of all: the enormous quantity of projects and installations, distributed in many scattered spaces: Giardini, Arsenale, Forte Marghera, outdoor areas, different neighborhoods. This makes the visit demanding: long times, travel, fatigue, risk that the average visitor grasps little beyond the “strong pieces.”

Some reviews complain that certain projects are too visionary, sometimes borderline speculative, far from any real concrete application. For example proposals that aim at outer space, or colonies on other planets, or submerged buildings: interesting at the conceptual level, but little useful if the urgency is that of daily life under climate stress. The risk that the “artificial intelligence” or “digital” component dominates too much in comparison with the natural or social part: that technology is presented as a solution that absorbs problems rather than change lifestyles or policies. Some installations are very performative but with limited capacity for real change. Critics note qualitative unevenness: some pavilions strike for depth, sophistication, care of materials, others much less. The Biennale, being so large, suffers the dilemma of selection: excellences emerge but also works that remain in the generic or the decorative. Despite efforts of circularity, recycling, dismantlable materials etc., some comments emphasize that an international Biennale, with global transport, specialist materials, large-scale exhibit production, cannot avoid a certain impact. Some projects require resources not always local or ecocompatible, which comes into tension with the ecological message. The risk that attention to climate adaptation focuses on spectacular topics (extreme heat, heat islands, vegetation, AI) but that systemic issues are missing: land consumption, housing policies, inequality, urban governance. Risk of cultural “greenwashing”: use of ecological, natural, sustainable themes as aesthetic or poetically seductive forms, but with little depth in changing real practices of building, investment, governance. Some critics signal this.

However, overall, Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 is one of the most ambitious editions of recent years, thanks to the breadth of participation, the strong attention to the theme of climate change, innovation (materials, biomaterials, use of sensors, adaptability), and the attempt to make the exhibition more circular, modular, responsible. Very interesting are the proposals it has given us, which make it, as always, a “must see.”

Projects and encounters and words for a futurepresent

Adaptation. Intelligence. Matter. Community. Heat. Risk. Balance. Utopia. Fragility. Coevolution. Imagination. Rootedness. Prototype. Circularity. Nature. Responsibility.

The Exhibition attempts to trace new routes for the future, suggesting a range of design solutions to the most pressing problems of the present. It brings together a collection of experimental project proposals, inspired by a definition of ‘intelligence’ as capacity to adapt to environment starting from a supply of limited resources, knowledge or power. Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 presents itself as a composite fresco, at times contradictory, but necessary: a global laboratory in which architecture, science, art, technology and collective conscience intertwine in the attempt to face the uncertainty of our times. From hightech installations to humble interventions rooted in territory, from reflections on extreme heat to strategies for urban selforganization, from experimental materials to returns of earth and forests, the show does not offer one single answer, but multiple visions in tension. Traversing the pavilions of Intelligens, the visitor moves between possibility and limits, imagination and responsibility, questions and trials. The greatest merit of this edition perhaps is not to offer certainties, but to expose contemporary design to its most urgent stress test: that of the climatic, social, urban future. And to ask, with courage, how we can still inhabit the world.

Words by MATILDE CRUCITTI

Photography by DONALD GJOKA

What to read next