Xianglong Li

Xianglong Li approaches memes not as fleeting internet jokes, but as raw material for rethinking how images travel between screens and canvases. Online, humor flashes by, reduced to shortcuts of recognition. On canvas, Li slows this speed, letting contradiction, distortion, and reflection settle in. What was once a passing glance becomes a site of thought.

His work often plays with mistranslation, as seen in the Learning Chinese projects. Here, comedy surfaces through miscommunication, but also reveals how language carries power. For bilingual audiences, the slippages feel familiar, resonant with lived experience. For others, the work may appear as quick entertainment, echoing Neil Postman’s idea that screens flatten complexity into spectacle.

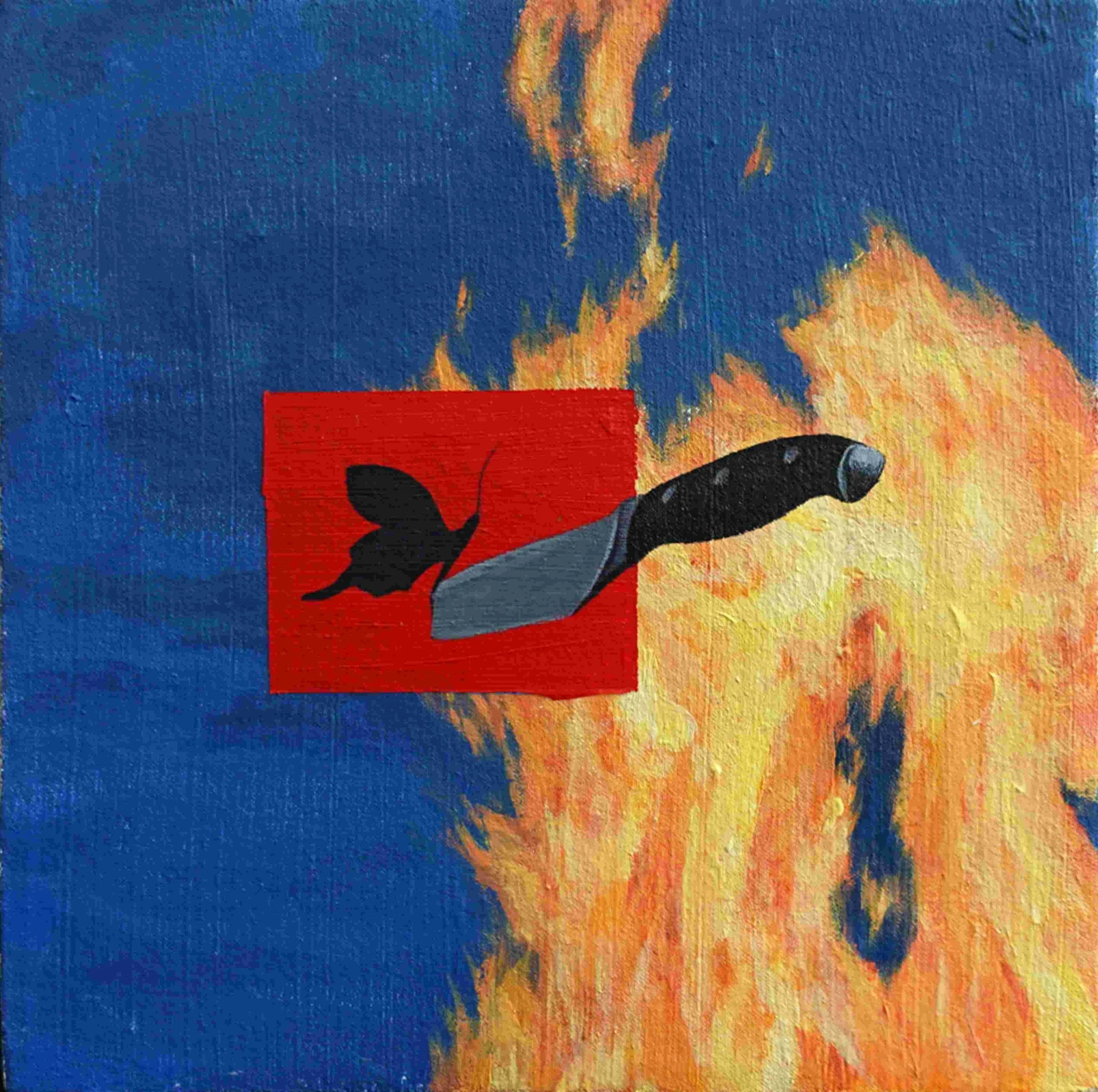

Humor remains central, but Li treats it as more than a punchline. He speaks of “negative positivity,” the possibility that failure, despair, or even injury can open toward absurd relief. A concussion once gave him the sensation of watching life unfold outside his body, yet he recalls it not with fear but comic release. That same paradox runs through his paintings, where satire and unease stand together. In Swim Around, a high school snapshot of classmates posing with machetes collides with an honor roll display.

The clash of rebellion and pride becomes ridiculous, but also revealing of youth, authority, and performance. Li’s practice builds on such collisions, showing how humor can shift perception, bridge divides, and give form to the strange logic of shared culture.Music as algorithm, style as template, intimacy through a screen. Orrin avoids lamenting these conditions. He builds inside them. The songs may feel euphoric, but they remain layered. Their energy carries uncertainty, confusion, and disconnection. Still, they move. And that may be the point. When language fails, when signals cross, when everything is lost in translation, rhythm might still reach you. Orrin places his faith in that.

With memes and digital collage playing such a big role, how do you approach translating these online-born aesthetics into traditional physical mediums like painting?

What interests me about memes is how they work like mental shortcuts; you see a familiar image and instantly know the kind of joke it carries. But on a screen, everything is fast and scattered, you don’t really pause. On a canvas, that speed disappears. Painting slows things down, leaving space for distortion, contradiction, reflection.

So, I’m not “quoting” memes, I’m re-engineering ways of seeing, taking something built for quick recognition and stretching it into a slower, more open experience.

Your satirical "Learning Chinese" projects play with mistranslations. How do audiences from different cultural backgrounds react to your humor, do you notice varying emotional or interpretive responses?

In Learning Chinese, mistranslation is both funny and revealing. For bilingual or overseas Chinese audiences, it resonates, they recognize the subtle miscommunications. For many Western viewers, it just reads as a quick TikTok joke. Like Neil Postman said, screens push everything toward entertainment, which can flatten complexity.

Can you share an example where “negative positivity” in your work helped someone reframe a personal hardship or absurd moment?

I once had a concussion that left me briefly unconscious, and the experience still sticks with me. It felt like a scene from Enter the Void, I was floating outside myself, watching my whole life unfold. But the images weren’t my memories, it was more like my body was remembering on its own.

When I woke up, I didn’t feel fear. I felt this absurd kind of relief, like the chaos itself had released me. That’s what I mean by “negative positivity”: turning despair or failure into something comic, even freeing. My paintings carry that same absurdity, where unsettling moments sit right next to humor, opening space for release.

Memes evolve rapidly. How do you balance the urgency of capturing meme culture’s ephemerality with artwork, which is often more lasting?

What fascinates me about memes is how they compress whole experiences into a single image and a few words,then you feel an instant connection, like being part of a bigger conversation.

In my work, I’m not trying to freeze a specific meme, but to translate that immediacy into painting. A canvas slows things down, but it can still carry the rhythm of mutation and shared recognition.

You mention connections from street culture and banter. Could you reflect on a memorable moment in those spaces that directly inspired a piece?

One moment that really inspired my painting Swim Around came up when I was looking through my high school photo albums. I found a photo I’d taken of two classmates holding machete at the school gate. I honestly can’t remember if they were just trying to look cool and rebellious or gearing up for a fight with others, but the image was hilarious.

What made it even more absurd was the background: the school’s honor roll, with pictures of top students posted right at the gate to show off academic achievement. The contrast of these two kids playing with knives in front of all that pride and order was just ridiculous.

As an artist and cultural educator, what role does humor, especially cross-lingual humor, play in bridging divides?

For me, humor is a secret weapon. It’s like stand-up comedy, you laugh first, but then you realize your perspective has shifted. Humor lowers the barrier, but it also opens up deeper questions about culture, identity, and communication.

Interview by DONALD GJOKA

What to read next