Boris Acket

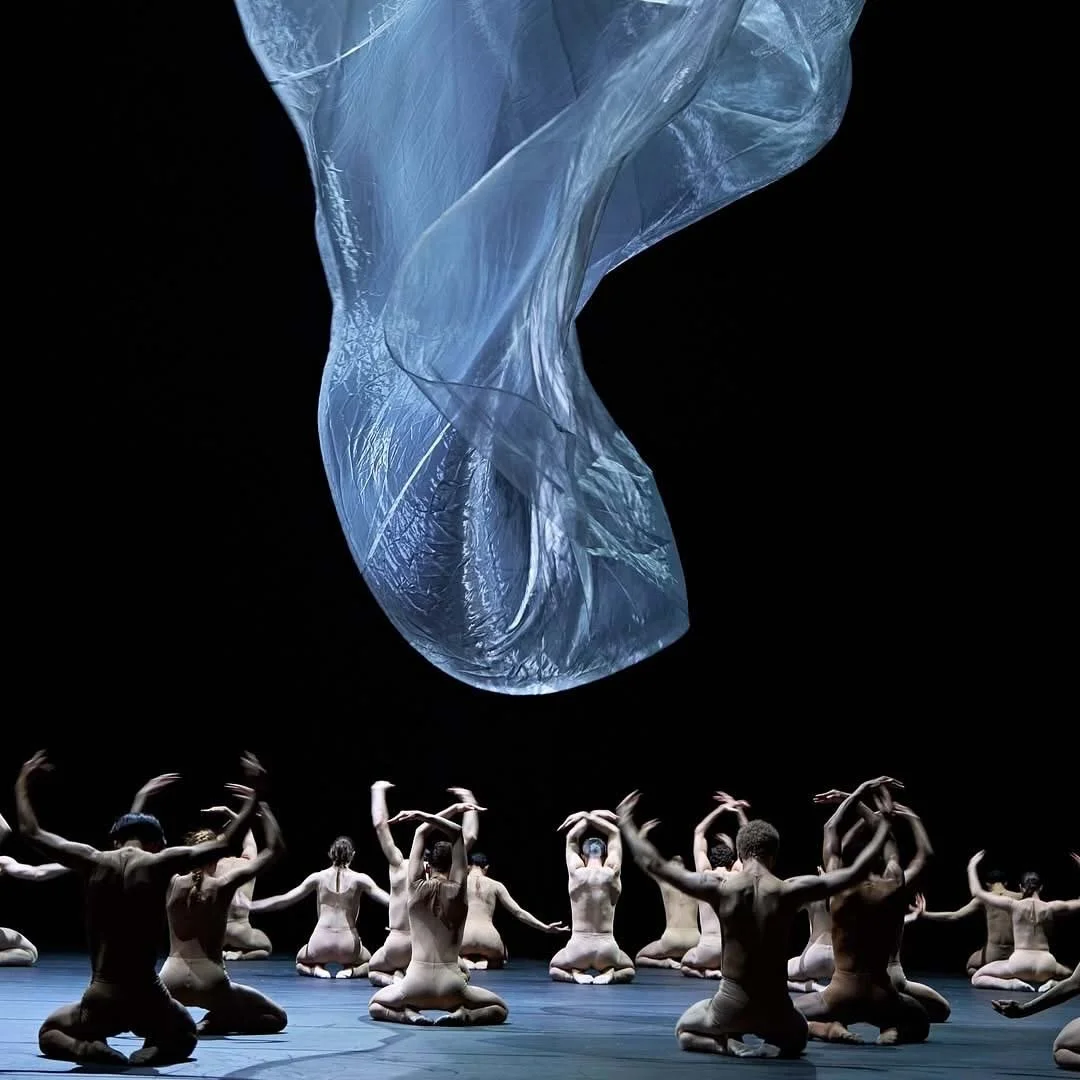

Boris Acket’s work toys with the idea of the artist as a god, manipulating the weather in a way usually reserved for the divine. His fabric installations imitate storms with such a convincing character that audiences can stare at them for hours on end, claiminBoris Acket’s work toys with the idea of the artist as a god, manipulating the weather in a way usually reserved for the divine. His fabric installations imitate storms with such a convincing character that audiences can stare at them for hours on end, claiming that they have never felt so immersed in nature. It’s a strange confession to make about something so obviously artificial, yet it points to the core of Acket’s practice: work that functions less as an illusion than as a mirror, reflecting our human need to mediate nature through technology, finding the real through the synthetic.

In this chat, Acket talks about his path from teenage clubber to artist, the paradox of controlling technology and surrendering to it, and why his installations might bring us further from nature but closer to each other.g that they have never felt so immersed in nature. It’s a strange confession to make about something so obviously artificial, yet it points to the core of Acket’s practice: work that functions less as illusion than as a mirror, reflecting our human need to mediate nature through technology, finding the real through the synthetic.

Your practice emerged from electronic music and club culture before evolving into artistic installations. Can you take us back to those early years in the nightlife scene? What did you learn about sound, light, and space from that context?

It all started with music for me when I was very young. I was 6 and tapping on everything, so my parents enrolled me for drum lessons. Then when I was 11 I got a sequencer program, and I basically stopped drumming and started producing more music because it was much more rewarding to be able to work on something for a few hours and then listen back to it. Music was one of the few things that I did pre-tutorial times and I think that's a very big difference from what we have now. I started making music with Logic and all these programs, and always used the demo versions. I guess I did a lot wrong as well which I do like in hindsight, I was just trying.

I got into clubs around 15, 16 and I always liked to move myself into the groups that organized the parties. And the first thing that electronic music really gave me was that method of creating a stage for yourself and a group around you. That method is still very present in my practice at this point. I really love to create spaces and then put people on them with my own art. I think that's a very good method to create context but also learn about context.

The other thing is that when I was in electronic music, making music, I was really religious about it. I’m not like that anymore, but at some point I really thought there was a bigger truth in it. What I was really fascinated about was when you were awake for way too long and you can see the light, you see the sun rays, but you also see the cars moving past the road. I was always very fascinated by these spaces that are just outside society, that run on their own clock and with their own rules.

Foucault writes about heterotopia and it's about this heterotopic concept of a space outside of society where all these other things come together. I'm always a very unrested person, I would say. Being in the now always fascinated me but it was more pressed upon me when I was in these spaces, basically because you are all together and the sound is very loud so the world becomes very strange. It’s also very strange that we voluntarily go into these very loud environments, there’s a ritualistic aspect to it as well. It’s communal even though you don’t really speak to each other.

At one point, I made some speaker sculptures that were a transition from club to artwork, they had arrays of speakers and arrays of stroboscopes. The juxtaposition between control and surrender is a very present theme in my work, and it’s also very present in the club experience, in the sense that you lose control for a second and surrender to what is happening around you. And in that ecosystem of speakers you also had to surrender to the system as a maker.

About this theme of surrender and control, your work Einder Hydrosfeer introduced an autonomous weather system, designed to remove agency from the artists. Can you talk about the paradox of using technology to create something you cannot fully control, about surrendering to your own design?

We started this series of works with our studio neighbors, Lumus Instruments, with this linear actuator version which is basically a curtain that is moving and you can modify its shape through some motors. We were looking at it and it was just so fascinating because it was a very simple movement, and if you would move all the motors front and back in a boring way it was actually the most beautiful motion. Then we were also captivated by how changing the resolutions would change the shapes slightly.

There’s this interesting relationship we, as humans, have with our own consciousness, the curse of always wanting to control things while simultaneously trying to surrender to them. Are we part of something, or separate from it? That tension becomes more evident when we work with nature, which connects to what you were saying about the later iterations of the Hydrospheer series.

The fabric material itself is incredibly rewarding to work with, these ultra-lightweight screens, under 21 grams per square metre. They’re woven with a glass-fibre-like thread, not actual glass fibre, but similar enough to create this beautiful refraction, almost like the surface of water.

I was with a programmer in one of the iterations for a museum, and we were fantasising about a version in which we could not control the system anymore, basically creating an autonomous weather system. I still don’t know why we did it, but then we were very deep in it. We began generating the thunders before you could hear them, pre-buffering the sound, sending it to the light engine so the thunder could match the light, etc. We ended up having this subjective system creating three thunderstorm cells, with nothing to do with an actual weather system but it was very complex nonetheless.

I was very fascinated with the idea of why are we doing this? Also when exhibiting it in Berlin it was very funny that people were voluntarily lying underneath it for an hour and a half, then coming to me and saying “I never felt so immersed in a storm!” Which is such a strange remark because you clearly know how synthetic it is. It’s a funny thing that people are looking for those hyper-real, hyper-natural experiences in these times. I think there’s something telling in that.

“I don’t believe in big revolutions but if I can make something that creates openness and gets you in a more childlike state I’m quite happy with that.”

Do you see these simulations as a way of bringing nature closer to audiences, or as commentary on our increasing distance from it?

I’m realising more and more that, well… first of all, it is a fascination. I find it very interesting that we are beings who look at our current moment through memory and expectation. It’s the only way you can see water or a storm in a piece of cloth that’s moving. There’s no other explanation for why we can see anything other than cloth as cloth, you need a memory in that moment to tell you, “Hey, I saw clouds yesterday, and they looked like this cloth.” So you take that into your present moment, and then you also expect something from it, and this brings you to this very non-logical conclusion.

I work with this acoustic ecologist, Gordon Hempton, and he confronted me with the idea that when we grow up, we get very conditioned. It depends on where you are in the world, but in general you get conditioned through your senses, they become filtered. Your eyes become filtered to the things you get used to, your ears become filtered to the things you get used to. He has this listening exercise with a microphone and headphones, field recording. I did a lot of field recording, and it’s always fun because you enter this familiar space, even your own house, and then you shrink yourself, and suddenly you’re walking through a very unfamiliar place. And then when you take your headphones off, you hear a lot more. Even without headphones, if you listen to the faintest sound, if you close your eyes and listen, it feels like your ears extend.

The microphone is important, Gordon says it’s a machine without a brain. And when you use that microphone and those headphones, and you turn the world up a bit, I think that’s a metaphor for the works I make. They are microphones, in a sense.

A director once said to me: “Boris, you’re actually making plastic trees.” And I found that a really interesting analogy, because it’s something very normal for us, at Christmas choosing a plastic tree instead of a real one, or putting a plastic plant in our home. And yes, I make very complex ones, but they are still plastic trees. This realization about us as a species and Gordon’s remark is beautiful, that he learned to listen and live again through the microphone and headphones, but it’s also funny that he needs the tool. We are this tool-based species.

The more I make these works, the more I see that they’re actually not about the subject they seem to be about. The fabric pieces appear to be about wind or water, but they’re also very much about the fact that you can see those things in them. They are maybe a mirror to us.

Also, it would be very arrogant to say that I bring people closer to nature. That’s not true. I think I bring them much further away from it. But I might bring them a little closer to each other.

You use fabric to simulate natural phenomena in the Einder series. Correct me if I’m wrong, but the word “einder” means horizon in Dutch, a border between Earth and the sky. How did this word become the conceptual anchor for these works?

What I like about the word Einder is that in Dutch when you look it up in the dictionary, it’s the imaginary border between the land and the sky. So there is space in the word, intrinsically, and I also like that the horizon is something naturally very imaginative, because it is eternal and there is always a new point in it.

“A director once said to me: “Boris, you’re actually making plastic trees.” And I found that a really interesting analogy, because it’s something very normal for us, at Christmas choosing a plastic tree instead of a real one, or putting a plastic plant in our home. And yes, I make very complex ones, but they are still plastic trees.”

Baken was a very emotional piece, a guiding light in the uncertain times of the 2020 pandemic. Can you talk about its origins, about the impulse behind creating something so visible and public during that moment of isolation?

We got commissioned by the harbour of Amsterdam during Covid times to make a public artwork, so we were thinking about what we could do that no one could actually visit because of the pandemic. I have a very big love for lighthouses; Dutch beaches in particular are very flat and big and empty, and then when it becomes dark you suddenly get all of these lights. I like that they sort of signal a presence, there is something reassuring and something very lonely about them, like about the collective loneliness of our species.

I found it funny that you see this lighthouse and it gives you the trust of being in a populated place, but on the other hand it represents this very lonely gesture of continuously signalling light into the black void, and I think there’s something really beautiful in that.

Your work is usually collaborative with different artists or technical experts. How important is the team in your process, and what does it add compared to solo practices?

The team is everything actually. It’s very rare that we do a project by ourselves. What I really like about the specific art form I’m in is that you never work alone, and you cannot work alone, because the works are simply too big. For example, I recently worked on a commissioned project for Fred Again’s tour and we had 50 people only on their side working on the basic infrastructure, we collaborated with a Danish company that produced a custom motor specifically to pull up this huge fabric, and then we worked with Corey Schneider who is an amazing programmer and developed the whole thing with us. Collaboration brings such complex things together.

“The more I make these works, the more I see that they’re actually not about the subject they seem to be about.”

Your practice has collaborated with many different worlds: museums, designers, fashion, festivals, etc. In which of the realities you have worked with do you feel most aligned with?

I don't know, there's something to a lot of them that I really like. What I like about museums is the control that you have over everything that you can do with a space. So you can literally go on until the level of what is on the signage, and how it's on the signage, and where the signage is, etc.

Then in theatre, which in my opinion is the queen of all arts, you have to montage technology, music, dance, substance, text sometimes, into one singular thing. It’s very exciting that again you have to surrender control because you’re working with people, and everything is different every time, there is no set system compared to museum work.

At this point I do enjoy the somewhat longer artistic processes. Now I have one going with Sabine Marcelis, which at first was just a mirror with a light that I asked her to do, and now we have this iteration with transparent glass wired into the ceiling and I just very much enjoyed making many small steps with it and getting really deep into the work. I enjoy the tours and the theatre but I am slowly moving into a phase where I really like to finish things nicely.

What emotion or state of being do you hope people carry with them after being in contact with your work? How much do you think about the audience when designing your installations?

It’s funny because in the process I make it for myself and for the space, but what I like about them in my own mind is that you can look at these things for eternity. For example in the waterworks with Sabine, when you look at it it’s not so clear but you get the gist of it, and then after five minutes maybe you know what is happening, but really you can look at it forever. I like the combination of honesty and the fact that the audience can figure out what is happening, but still has a sense of wonder, for lack of a better word.

There’s a listening exercise by Gordon Hempton, where you put a small child on your shoulders and walk with his ears to where he wants to go. I work with a sociologist who said it’s funny that when you are growing up your head literally grows distant from the floor and with that you also lose a bit of contact with the natural earth, as well as the ability to tap into your childlike self. I don’t believe in big revolutions but if I can make something that creates openness and gets you in a more childlike state I’m quite happy with that.

Interview by ANNA LAZZARON

What to read next