‘No Other Choice’ by Park Chan-wook

For the past fifteen to ten years, Korean cinema has been markedly critical, comparable to American cinema at the time when, in the Land of Opportunity, capitalism was consolidating and the ideology of career advancement projected itself into a material superficiality directly proportional to one’s salary.

In Korea, capitalism was rising while America was binding itself tightly to it. Now that capitalism consolidates in Korea, Korean filmmakers challenge it with the same energy that characterized certain auteurs, above all those of New Hollywood, between roughly 1955–60 and 1970–75. At that moment, in American and European cinema, a hungry desire arose to strip the capitalist dream to the bone in order to regain a legitimate and natural integrity. That satire was propulsive and confrontational, and initially sprang from repulsion toward the Vietnam War.

And perhaps it is no coincidence that, between the protagonist of No Other Choice and his fully realized horrors, there exists an element that connects him, through his family past, precisely to the Vietnam War.

For the past fifteen to ten years, Korea has cyclically returned to Western theaters to confront the theme of capitalism with the excess that distinguishes its cinema. In 2025–26, Park Chan-wook, born in 1963, returns with a forceful film about the role of work.

A film not about the role an individual plays in the job he performs, but about the role that work plays within a single individual.

A film that is highly articulated and fragmented, yet among the most compact Park Chan-wook has made, about people driven to despair by the loss of work, in which their despair first becomes existential.

Above all, it is a film of psychologies corrupted by the selective authority of a system that, by tradition, remains patriarchal, dominated by the free market and presented as democratic, while in reality governed by an atavistic dictatorial legacy that recalls the authoritarian policies of the former regime

The system decides arbitrarily what social affirmation means: professional achievement, the meaning of success. It then indoctrinates the individual to live solely in pursuit of this success, to compete in order to obtain it. A success that, when achieved and then taken away, especially when granted and withdrawn by the same entity, can drive an individual to commit brutal actions, such as killing a professional competitor.

Speaking of brutal actions…

In parables whose characters, even when negative, become deeply conscious and therefore instructive for the audience by grasping an ethic they previously lacked, popular cinema usually includes a scene symbolizing that they have “cleansed themselves” or “are cleansing themselves,” often beneath rain pouring over their heads. The characters of No Other Choice, by their social nature, are moral abominations. Always negative, they worsen by the end. They too, in the end, find themselves under heavy rain. In that scene, however, they carry umbrellas.

The company, by its very nature, stands as that which abhors human existence itself.

No Other Choice is a film about the devastating conditioning that work exerts on individual identity, especially male identity, within a social body that grows increasingly corporatized, where wealthier executives evaluate everyone’s existence according to the importance a job assumes in their affluent eyes and according to profitability measured against the most futile consumer goods.

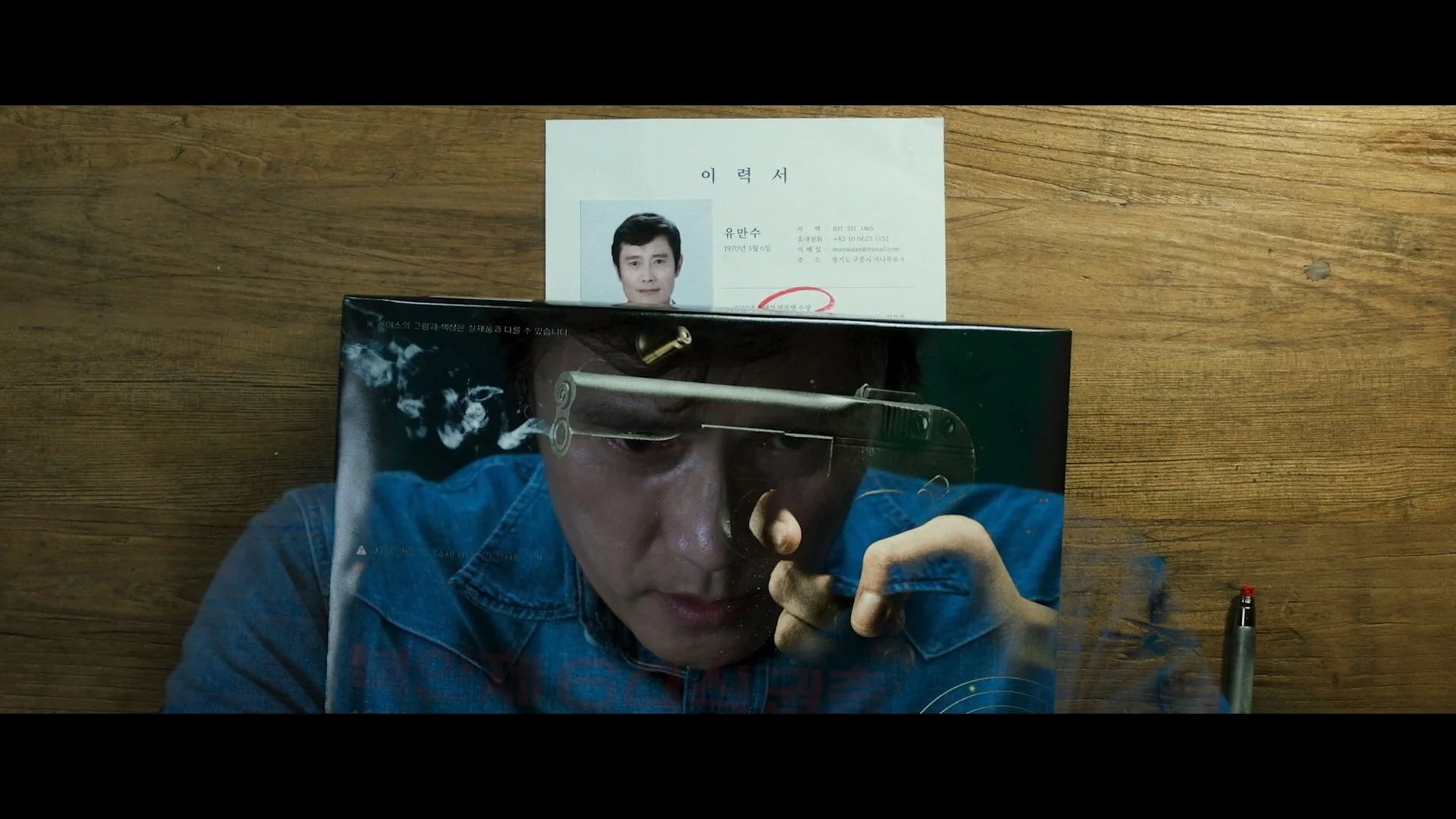

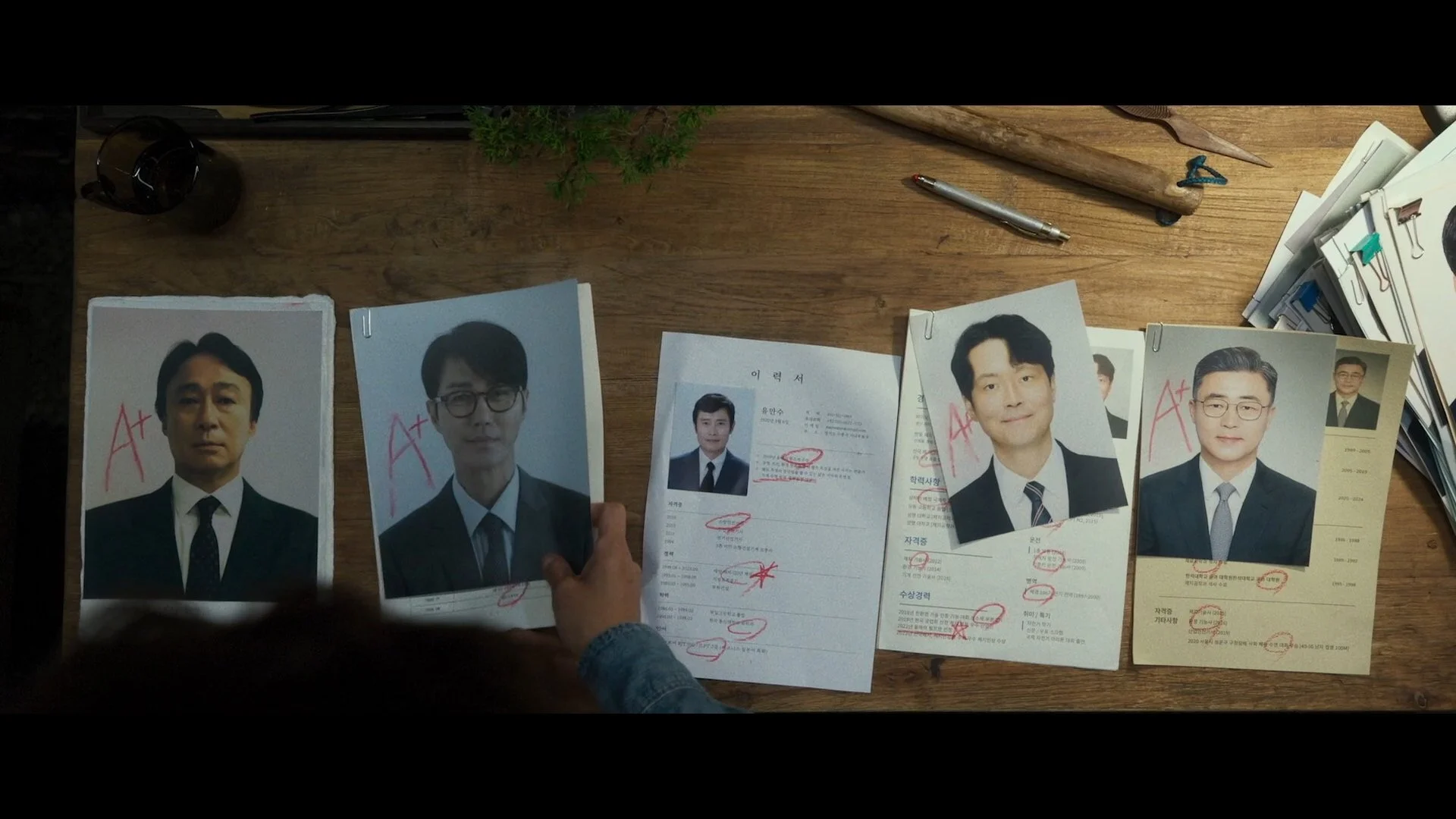

These are all critiques of capitalism and inequality, articulated through a frantic film that addresses its audience with derisive ruthlessness in the most expansive form possible. In one word: hypertrophic. The hypertrophy of a moment in the life of Yoo Man-soo, a middle-aged bourgeois man suddenly plunged into precarity, who, for his own ideal survival, undertakes a murderous battle to avert his imminent ruin. In a class-based Korea, where professional success stands decided at birth and irrevocably designated by family status, where no one can affirm themselves in sectors from which their families and ancestors have traditionally been excluded, Yoo Man-soo has already completed the climb and enjoys the reward: an object-family and a house he owns, filled with objects of bourgeois virility.

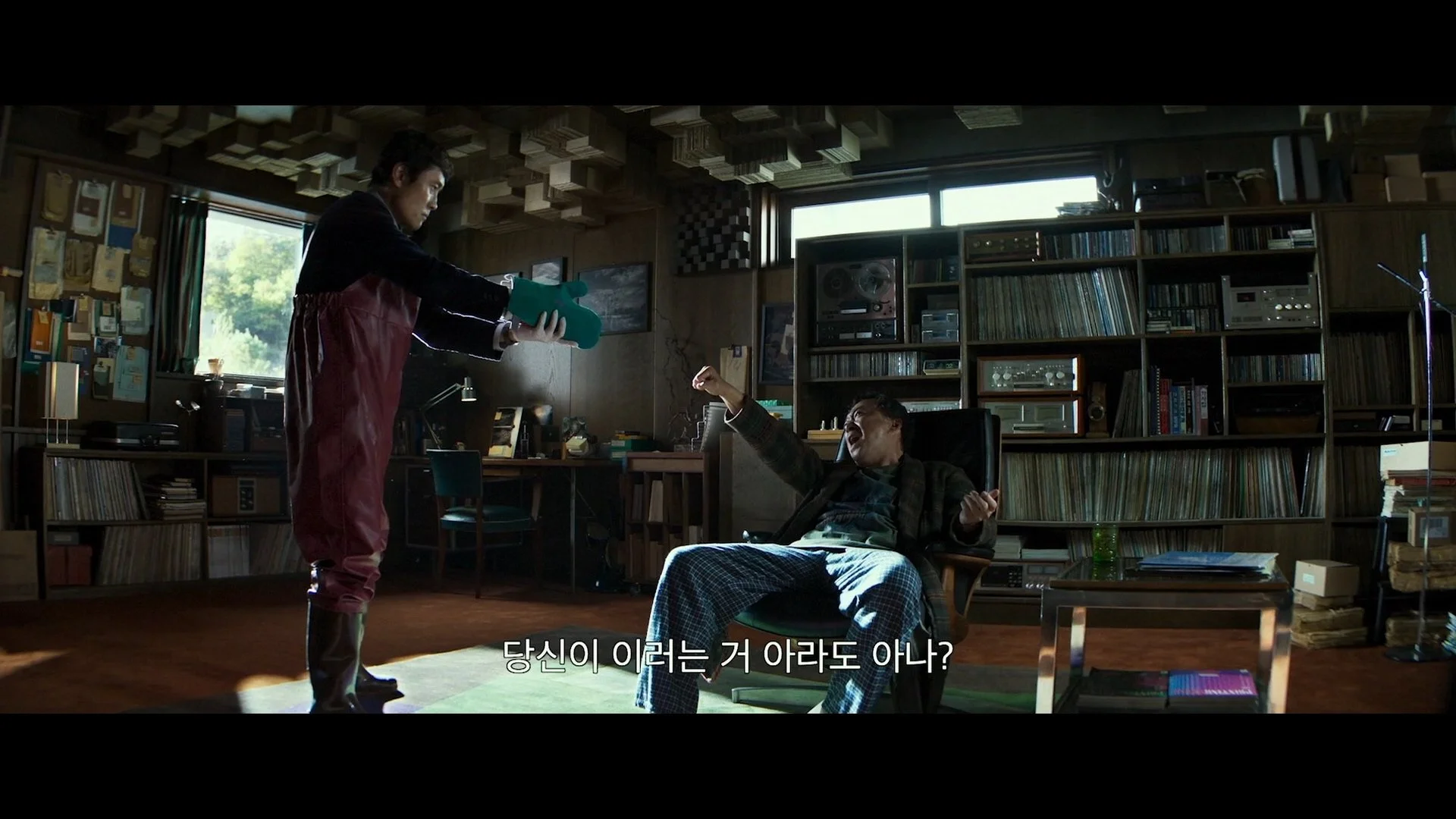

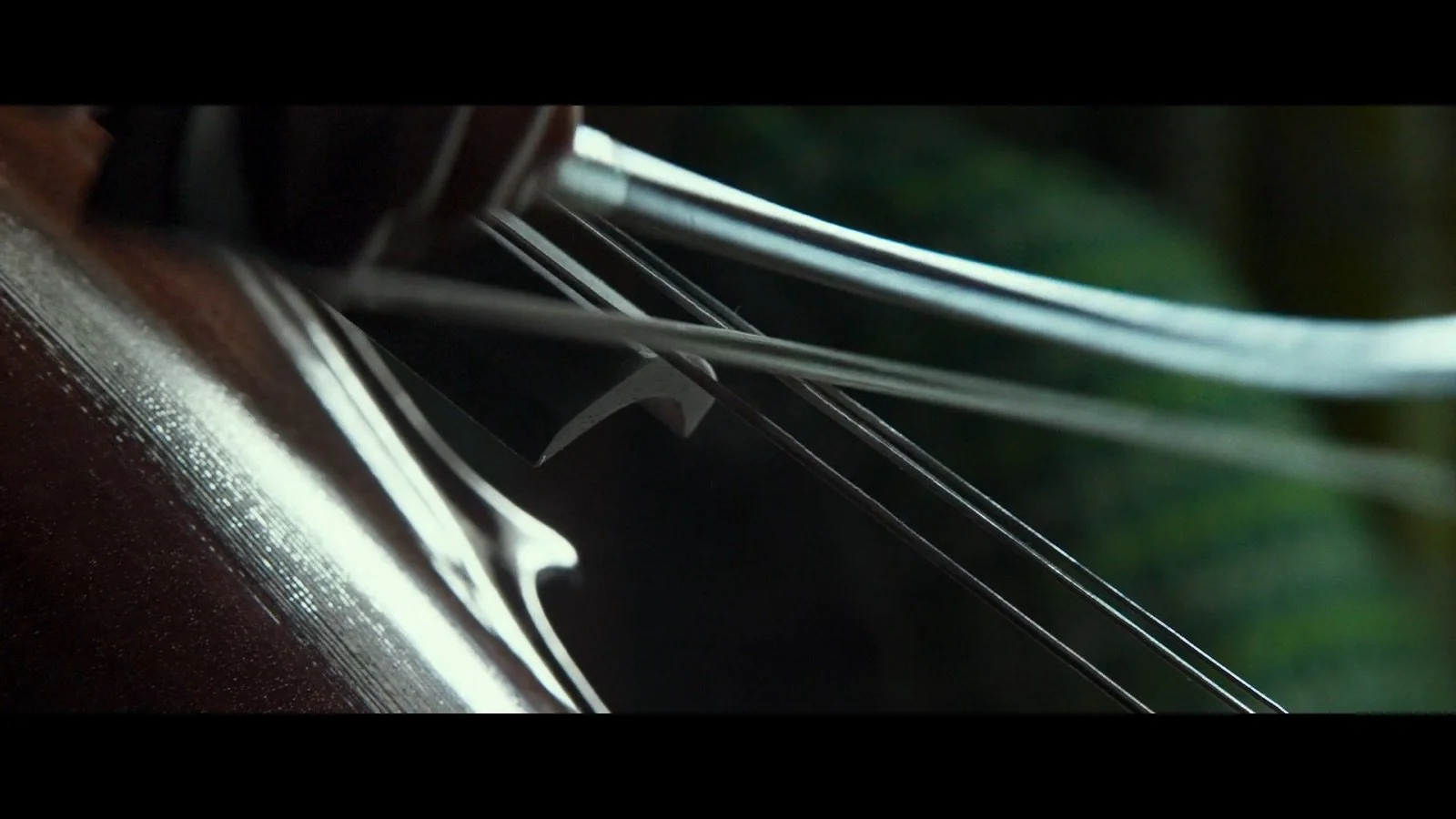

The large house. A wife who attends dance classes between one tennis match and the next. Two pedigree dogs, two. Two children, one not his and one a daughter, neurodivergent or autistic, a prodigious cellist. Of this he and his wife remain certain, even though they have never heard her play, despite having initiated her themselves into this prestigious instrument.

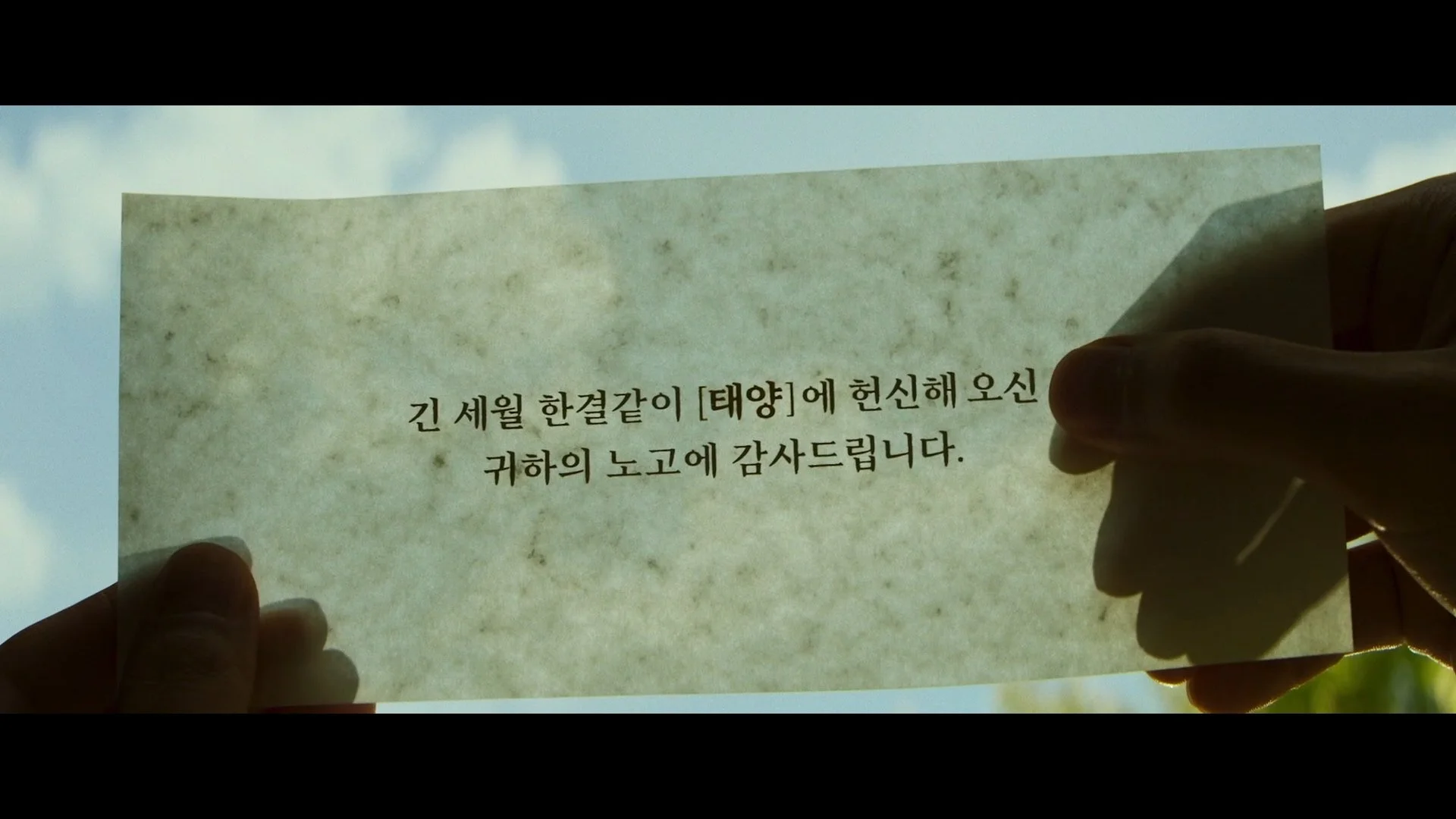

Man-soo lives a dream. In the idyllic warmth of a pre-autumn day, while the barbecue grill sears eel meat offered by the paper company for which he works, a gift he promptly misinterprets as an homage tied to his gender, delivered together with a letter of “thanks” for years of hard service, Man-soo, rather than sensing while reading the sweetened pill of his dismissal, appears, as he holds it in his hands, more interested in feeling the paper’s texture with his fingertips than in grasping its real meaning. Yes, our protagonist is an idiot.

He grabs his wife, they dance. Leaves fall gracefully. The sky looks beautiful, their driveway somewhat less so, like a computer screensaver. The entire family embraces, including the dogs. A glossy postcard. Man-soo remains blissfully unaware. Perhaps he does not believe it. He has realized himself, he feels he has arrived.

Unfortunately, shortly before this, a large American corporation appeared on Korean soil to absorb the company where Man-soo finally reached the highest level as an employee. To minimize costs and maximize output, the American company must cull staff.

In a country where a man’s work counts as a congenital attribute and being idle appears worse than being psychopathic, Man-soo, now unemployed, finds himself in the grim condition of continuing to live with the frustration of knowing he performs a job well but can no longer perform it. Other work remains possible, in theory, but he refuses alternatives. The current sectorization blocks any emancipation from the system that already employed him. Since positions still exist but opportunities to obtain them steadily diminish, Man-soo must understand that no other choice remains than slaughtering other unemployed men, those who worked in his same sector and gained credentials and qualifications superior to his.

His life snaps like the bonsai branch he bends beyond its limit. Lying on the couch, in a house he can no longer afford and refuses to abandon, he comes to understand that he must become a killer, while immersed in online platform advertisements that make utterly incompetent people appear as absolute professionals.

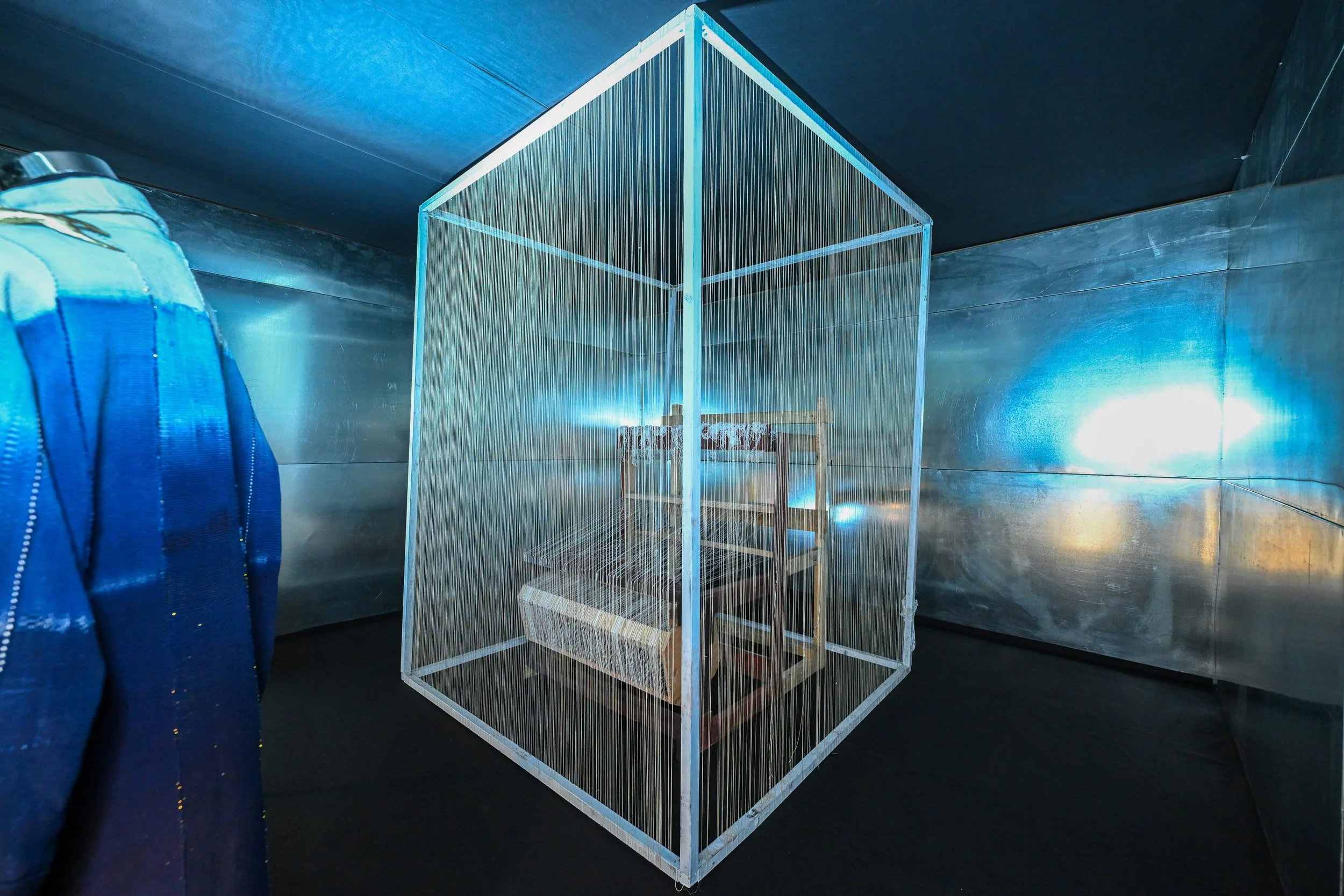

Within the overflowing contemporary river, where words, sounds, and images have been emptied of meaning, paper remains a tangible anchor, a support upon which to leave a mark: a gesture enacted within a real, physical, bodily space.

Here the entire paper-related question becomes significant in relation to where the film ultimately leads.

The paper mill that employed Yoo Man-soo for twenty-five years dismisses him after removing his possibility of operating outside the very company that fires him. It is a film that speaks of the impossibility of possessing multiple utilities, of the impossibility of flowing through different experiences, imperfect and perpetual, within an exploration. And of existing as a dehumanized cog within a productive complex that, at the first opportunity, leaves you stranded because it finds a profitable replacement.

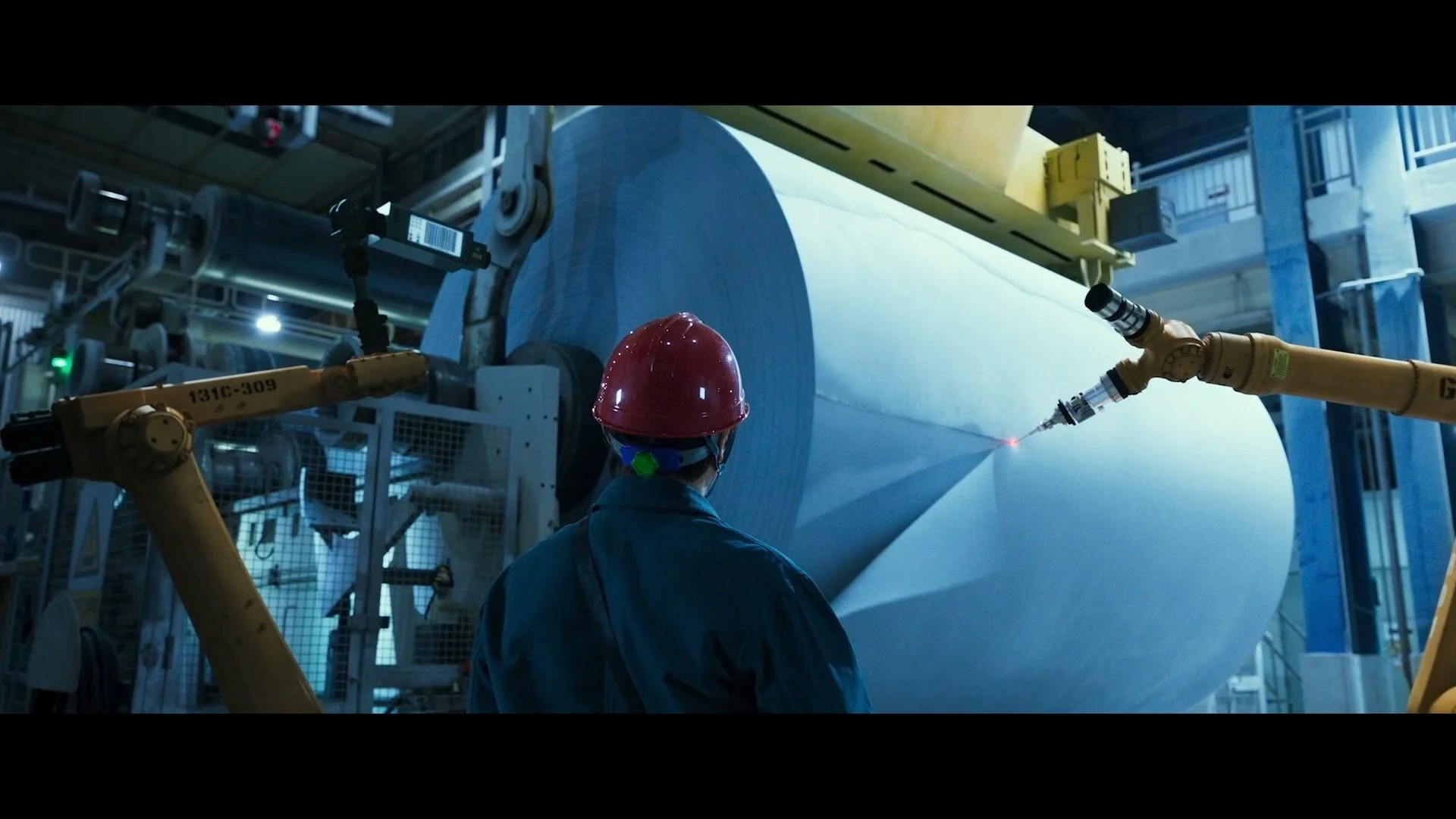

Acting differently from what one learned within the complex for which one had become indispensable becomes impossible. Indispensable, certainly, at least until innovation arrives through the use of AI. Here the film reaches a crucial point: the radical replacement of labor with AI.

Yoo Man-soo ultimately succeeds. Having eliminated the competition, he renders himself indispensable. He is called to work in a new paper sector, to operate and supervise a fully automated process. Leaving his future uncertain, Park Chan-wook widens the frame to deforestation carried out by machines controlled by people, questioning this time the future of a world that perhaps grows increasingly desolate and devoid of life.

In conclusion, this film by Park Chan-wook stands as hyper-constructed, playful, certainly postmodern and certainly political, since cinema always remains political, and at the same time poetic. Its planes of interpretation, already highly symbolic, intersect to generate new levels of meaning. As when the faces of the unemployed men Man-soo must kill overlap, semi-opaque, with his own. Or when ladybugs that have arrived to colonize and devour the pear tree in his garden overlay Man-soo’s face as he watches a victim. Or when the wife’s body merges with the soil, softened by rain, which the husband shovels while digging a grave. A grave that must also contain fertilizer for his plants. Plants that belong to him: Yoo Man-soo, amateur killer, multi-award-winning veteran of the Solar Paper company, and an excellent green thumb.

In the nocturnal blue, illuminated by moonlight, wearing velvet pajamas, she lies on her side, asleep, superimposed upon the fertile earth, becoming a consequential part of the scene, precisely as the husband’s shovel forces her to change position.

No Other Choice

Directed by Park Chan-wook

Words by ENEA BOCCAZZI

What to read next