Jojo Gronostay

How can we disrupt embedded hierarchies? Those that are not only forced upon us but written into the structures and mechanisms that encapsules our bodies, our societies and realities. As pointed out by Olesia Shuvarikova in her essay for Jojo Gronostay’s exhibition Afterimage (Composites), hierarchies are maintained through order. To resist one must break this order apart.

Through distortion and fragmentation of objects, stories and realities, Gronostay revolts the current order of things. Applying acts of disruption, his work borders on abstraction, but remains its political and societal edge, inviting audiences to reflect on questions of value and distribution between the Global North and South. Where is value constructed? What makes something valuable? And to who does this value apply?

For his second solo at Galerie Hubert Winter in Vienna, he is continuing his in-depth dedication to the never-ending layers of value and value-construction in the clothing industry. In a new video, series of photographs and paintings, our gaze is directed to vintage trading in Ghana, and how this market has changed following the current secondhand boom in the Global North. Presented with clothes turned to waste, and previously wasted clothes reborn as fashion, or even art, one is faced not only with the complexity of this value system, but also the consequences of (over)consumption and lack of care for the fabrics in hyper capitalism.

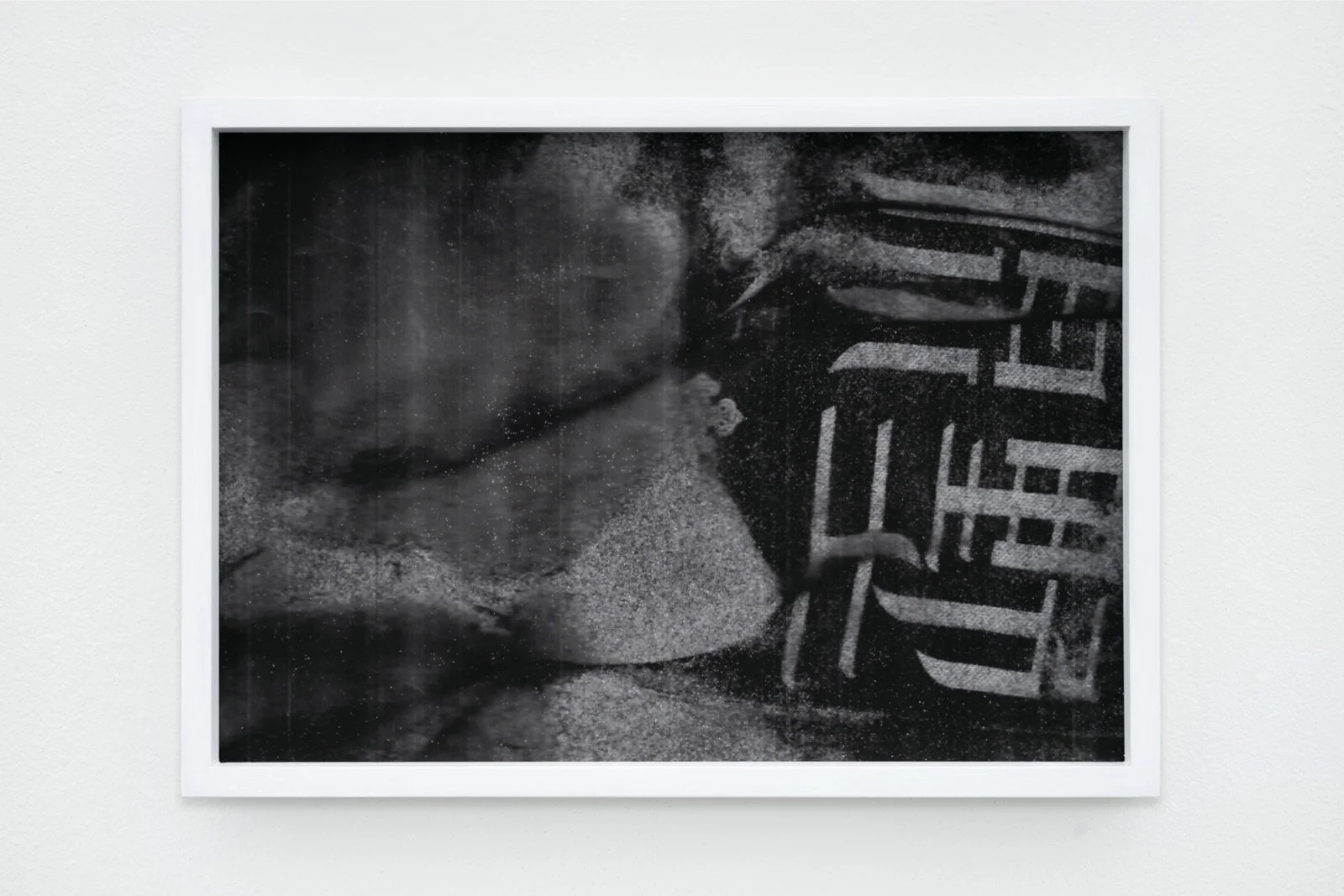

At the center of your current exhibition at Galerie Hubert Winter, is the entangled histories of fashion, or more specifically clothing, and waste. This is especially apparent in the photo series Landscapes that show imprints of clothing embedded in the ground of the Ghanian capital Accra. How did these «landscapes» come to catch your attention?

I had been noticing these traces for years, but I didn’t immediately know how to approach them. In Accra there is so much second-hand clothing arriving from the global North that it inevitably spills beyond the market. These clothes are also visible on beaches and streets. What really caught my eye was these in-between states: moments when the fabric has already taken on the color of the ground, when a garment is no longer clearly “clothing” but not yet fully “earth.”

In the end I used a handheld scanner to capture the ground as if it was a flatbed. Almost like taking an imprint rather than a photograph. The slow, brushing movement of guiding the scanner across the surface became important to me as an artistic gesture: part documentation, part performance, somewhere between archaeology, frottage, and image-making.

“I often think of a remark by the curator Okwui Enwezor on recycling and Africa: he points to the ingenuity of giving materials new lives, while also warning us not to romanticize recycling, because it is frequently the result of structural inequality rather than a celebrated choice.

”

The movement of fabrics from the global North to the global South has been a reoccurring topic for your artistic practice for almost ten years, expressed through long running projects such as Dead White Men’s Clothes (DWMC), a fashion brand that in essence re-introduced Western secondhand clothes that had been exported to be sold at the Kantamanto Market in Accra, Ghana. This specific project manifests itself in a variety of mediums, including your newest film The Elephant. What inspired this work?

I founded Dead White Men’s Clothes in 2017, while I was still studying. The name comes from the Ghanaian term “obroni wawu,” which roughly translates as “a white man has died.” In the 1970s, the quality of imported second-hand clothing was so high that when the first big waves arrived in Ghana from the global North, people couldn’t believe someone would give these garments away, so they assumed the previous owner must have died. Today, a large portion of what arrives is unwearable.

I go to Ghana regularly and source items at Kantamanto Market in Accra, one of the biggest collection points for used clothing worldwide. I collect pieces, relabel them, and bring them into new contexts. In the beginning, I often built pop-up store structures inside art spaces and “returned” the clothes to the global North, reintroducing them into a system of selling and display. That tension between fashion and art, between commodity and artwork interests me.

But the project has changed a lot over the years. Now I increasingly see the garments as props: materials for performances, video works, and installations. The label has also become a framework for collaboration with other artists.

The Elephant comes directly out of that. The film is two things at once: it documents a public performance or clothing presentation we did in Winneba, but it also works as a standalone video work. The stilt walkers started as a practical solution; my question was: How do we draw attention in public space without building a stage? Stilts make the body visible immediately. Later I learned that in parts of West Africa, the stilt walker is seen as a spiritual figure, a symbol connecting the here and the afterlife, which felt fitting for Dead White Men’s Clothes.

The Elephant is in its entirety is made in Ghana, with Ghanian staff in front and behind the camera, in what way does this contribute to the final work?

Having the film made entirely in Ghana, with a Ghanaian cast and crew, was important to me. It’s not only an “intercultural” collaboration; it changes the perspective. I’ve been working for years with a team in Accra across different projects in the DWMC context, so there’s trust and continuity in how we work.

Beyond that, questions of infrastructure and value are crucial. Who gets paid, who carries the work, and how value circulates. These things are part of the artwork for me. Production is not neutral, and I can’t place myself outside of complicated power relations. I’m in it. Choosing to build the film there is also a way of redistributing resources, not just extracting images or stories.

Beyond the visually intriguing stilt walkers, The Elephant also has an amazing soundtrack, composed by Sami Mandee for this occasion. What fostered this collaboration?

Sami and I have known each other for a long time. He’s also a visual artist, and in my videos, sound is always a conceptual layer, not just an add-on. I really see sound as crucial to how the work functions.

Another musician I’ve collaborated with on video works is Sofie Royer. Often the music becomes the starting point for the entire structure of a piece. That’s why I have a huge admiration for musicians.

When I was 18, I stopped playing soccer and thought I wanted to become a DJ. Somehow, I never actually DJed. Music felt too important to me, the stakes felt too high. Haha

“Production is not neutral, and I can’t place myself outside of complicated power relations. I’m in it. Choosing to build the film there is also a way of redistributing resources, not just extracting images or stories. ”

Concepts of value and devalue, understandings of waste, re- and up-cycling, are core subjects throughout your practice. What sparked your interest in these questions? And how do you see them in relation to the post- and neocolonial relationships dominating the global North-South axis?

These questions grew out of watching how “value” is produced through systems of circulation: what counts as new, useful, and desirable in one place becomes obsolete, surplus, or waste somewhere else. I often think of a remark by the curator Okwui Enwezor on recycling and Africa: he points to the ingenuity of giving materials new lives, while also warning us not to romanticize recycling, because it is frequently the result of structural inequality rather than a celebrated choice.

In that sense, re- and up-cycling can’t be separated from the politics of resources. The massive flow of second-hand and obsolete goods shipped from the “West” to African countries is tied to post- and neocolonial relations: Africa is too often positioned as the destination for the outmoded and the remainder, absorbing the externalized costs of Northern overconsumption. So, when I work with discarded materials, I’m not only interested in transformation as a formal or poetic gesture, but in what these materials reveal about global infrastructures of extraction, disposal, and responsibility.

For me, it also raises questions about “saving” and “helping”. Donating can sometimes feel like a quick way to ease guilt, while the bigger system of overproduction and waste stays the same.

I find what you remark on second-hand clothes as a consequence of lack of alternatives rather than a conscious choice as immensely interesting. If we apply the same logic to the current trend of second-hand clothes in the global North, we can also see this as interconnected with the increasing class disparity here, where a growing amount of the populations also are faced with relative and/or real poverty. This brings me to Angela Davis’ Women, Race, and Class, where she argues that it’s in the interest of the financial elite to – borrowing the words of Julias Caesar – «divide and conquer». Do you believe art and artist can play a role in mending these divisions?

Yes, I think that’s true. The divisions are growing wider right now. I’m not sure I would claim that my work can change that in any direct way. But I do believe art is incredibly important for sustaining a functioning society, and art genuinely “saved” my own life.

With my work, I hope to create spaces where people can reflect on connections, between class, consumption, and the systems behind them, and that this reflection might lead to small shifts in how we see things, and maybe, over time, to small changes.

“Darkness for me is not atmosphere; it’s a condition.”

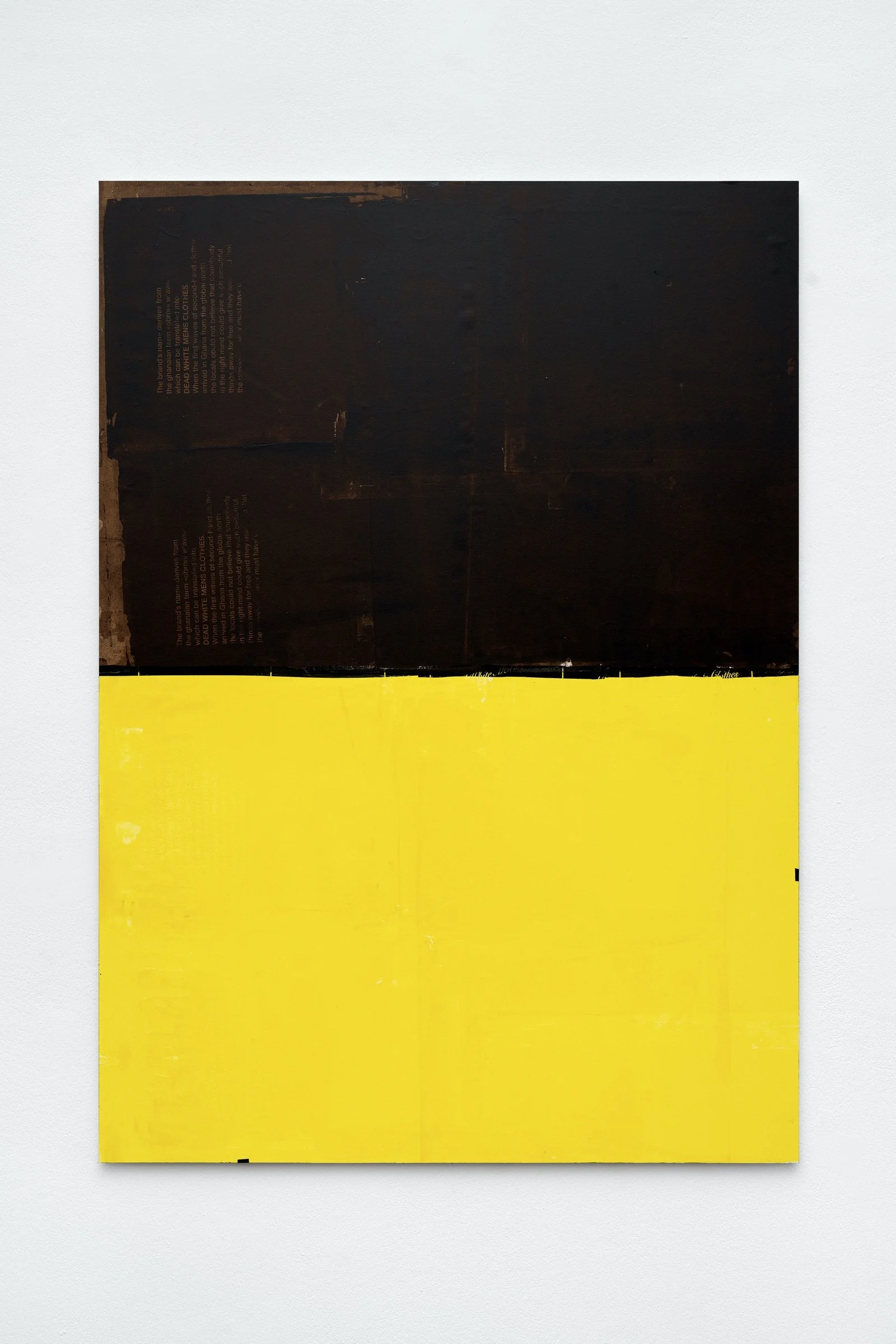

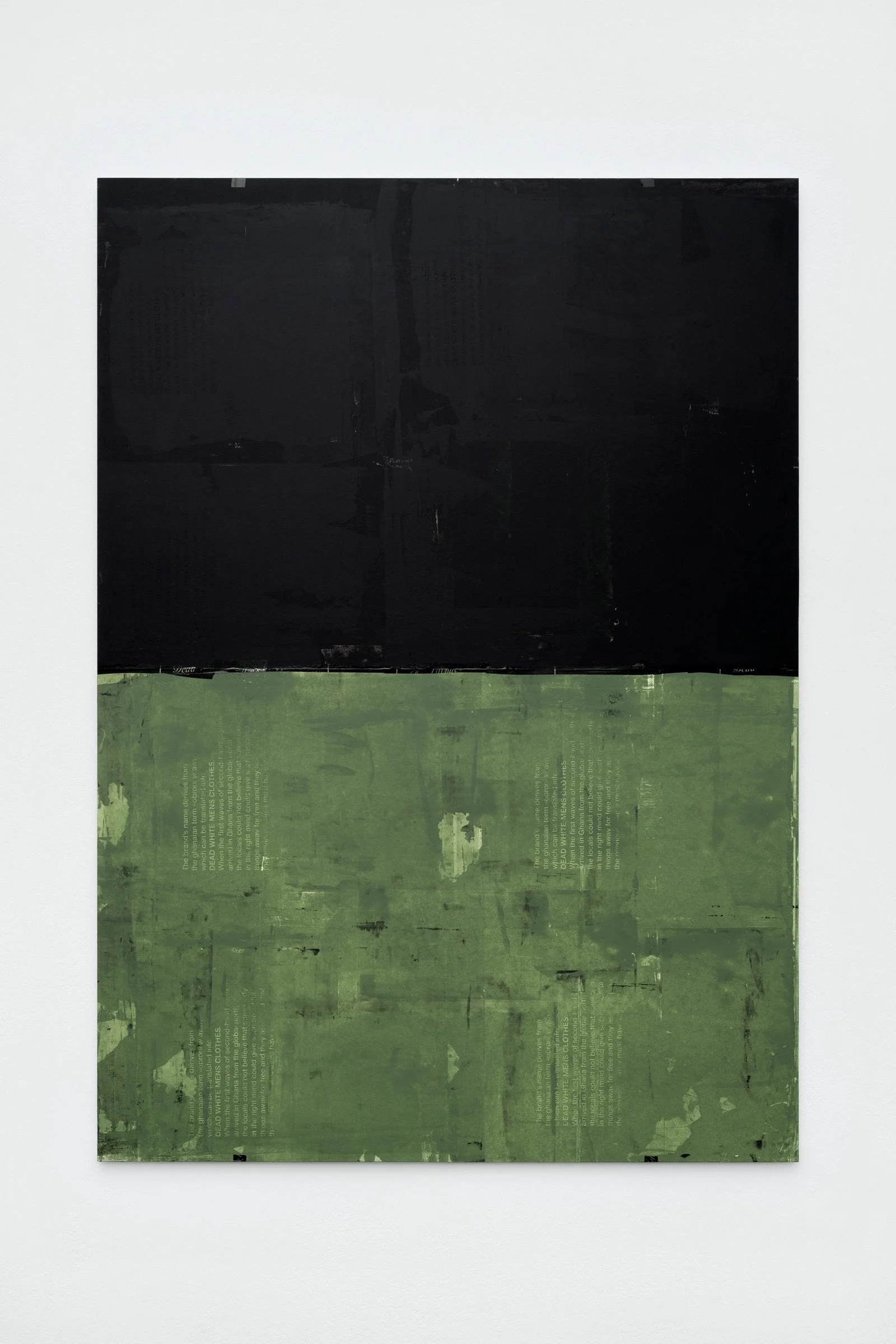

At Galerie Hubert Winter, you are taking your exploration of value to a new meta plan through a series of silkscreen prints, under the title Untitled (Afterimage) 01-10. In the arts, prints are typically coined as sellable, and in that sense these works seem to explore a more commercial potential of the arts. As with the cloths presented through DWMC, also here you are re-using material. How do you see this new series of work in relation to your overall practice?

I was again drawn to the leftovers of the DWMC system. I used old, damaged silkscreens that I’d previously printed the clothes with, and even the DWMC packing tape I used for shipping the boxes. The prints literally come out of what remained from the label and its infrastructure. For me they’re like an afterimage: a trace that stays once the “main image” has moved on.

Like I said before, the clothes are not my main focus anymore. Every time I go to Ghana I bring less and less clothing “back.” That shift also connects to a question I keep returning to: can DWMC become its own ecosystem, with its own materials, rules, and leftovers?

In a way, I’m placing the same material into a different value system. Visually they read almost modernist from a distance, but the closer you get, the messier and more physical they become. Usually, I live with works in my studio for a long time before showing them; with this series I didn’t, so they still feel a bit foreign, but I guess that’s also what makes them exciting for me.

For your exhibition, the inside space of the gallery has been darkened through window foil that prevents light from entering. I find this constructed ambience interesting in relation to the interconnection made between the European enlightenment and colonialism, by Franz Fanon amongst others, where the Europeans were said to «(en)light» the other continents. Following this thread, the darkness can be seen as a protest towards colonial hegemony per se. With questions of de- and recolonization as such central markers in your work, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the potential of darkness as an expanded form?

I really like the question and your association with the European enlightenment. I wouldn’t have thought of that. I’ll give a very short answer to your question: Darkness for me is not atmosphere; it’s a condition.

Interview by UNA GJERDE

What to read next